Exhibition | Alexander Roslin: Portraitist of the Aristocracy

Alexander Roslin, John Jennings Esq., with His Brother

and Sister-in-Law, detail (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the Rijksmuseum Twenthe:

Alexander Roslin: Portraitist of the Aristocracy / Portrettist van de aristocratie

Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede, The Netherlands, 18 October 2014 — 12 April 2015

Beauty, wealth, power and prestige: the Swedish painter Alexander Roslin had an unerring grasp of how to portray the ruling class of his time. As a travelling portraitist in the second half of the eighteenth century, he visited the European centres of power to portray kings, queens and other members of the aristocracy and nobility in their finest dress. The exhibition, Alexander Roslin (1718–1793). Portraitist of the Aristocracy gives a wonderful overview of a turning point in history. The portraits of Roslin are personal documents of a period that is coming to an end, one of limitless power, extreme poverty, of beauty and atrocity. It was perhaps a tense and nervous time in modern history, which fell like a house of cards and changed Europe forever.

Le Chevalier Roslin, as he was sometimes known, immortalised the ruling class at the height of its wealth and power. He was the chronicler of the wealth and decadence of the late eighteenth century. But this ‘pageant’ was with hindsight the last spasm of a class that would soon lose its power and prestige. These were turbulent times: political and social unrest prevailed, which reached its climax with the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. Many aristocrats who were painted by Roslin lost then their high positions and corresponding status. Some even literally lost their head under the guillotine or died a violent death through other means. The fact that Roslin himself, as representative of the hated ruling class of the Ancien Régime, miraculously survived the Revolution is probably due to his not being a French citizen.

This first Roslin exhibition in the Netherlands is not only a unique opportunity for the Dutch public to get to know the wonderful work of Alexander Roslin, but it also draws the visitors into the world of the aristocrats he portrayed. Their fascinating stories, which were sometimes dramatic and always personal, and which included political and moral intrigues, form the thread which guides the visitor through this exhibition. The luxury in which the portrayed class lived and the sweeping changes they encountered in their world are brought to life by objects from their entourage: costumes, furniture and porcelain, but also letters and prints. An intriguing picture is given of a class and way of life which experienced its climax in Roslin’s time, just before its downfall. In this way we get close to the artist and his clientele.

The exhibition will show in total more than thirty works from different international collections. Rijksmuseum Twenthe is the only museum in the Netherlands which has two portraits by Roslin in its museum collection. The delicately painted and elegant portraits of the French couple Marie Romain Hamelin and Marie Jeanne Puissant represent a type of painting that is unique in Dutch museum collections.

Especially for this exhibition RMT will have no less than sixteen top artworks on loan from the Roslin collection of the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, including Portrait of Gustave III and the Lady with the Veil, which was described by the famous French author and critic Denis Diderot as ‘très piquante’. From the collection of the Nationalmuseum there will also be portraits on show of the Swedish Royal family, such as those of the Swedish king Gustav III (1775) and of his dominant mother Lovisa Ulrika, princess of Prussia, queen of Sweden (also 1775). Members of the French Royal family and others associated with the Roi, including Louis-Philippe de Bourbon (1725–1785), duke of Chartres, later duke of Orleans also figure prominently in the exhibition. The aristocracy is well represented in the exhibition, with wonderful portraits of the Baron and Baroness de Neubourg-Cromière (1756). One of the highlights of the exhibition is the dual display of the portrait of Princess Hedvig Elisabet Charlotta of Sweden and the original bridal dress which she is wearing on her portrait.

This exhibition has been made possible through the generous support of: Nationalmuseum Stockholm, Friends of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds (Nieske Fonds), Mondriaan Fund, VSB Fund, SNS Reaal Fund.

400 Years of Friendship between Sweden and the Netherlands

In 1614 Sweden opened in the Netherlands its first-ever embassy. This was the start of a friendship which has enriched and continues to enrich our economies and societies to the present day. In 2014 we’re celebrating this friendship through a special activity programme. The exhibition Alexander Roslin: Portraitist of the Aristocracy is part of an international programme. Look for more information on www.swe400nl.com.

New Book | Solomon’s Secret Arts: The Occult in the Enlightenment

This book from Paul Monod (like John Fleming’s The Dark Side of the Enlightenment: Wizards, Alchemists, and Spiritual Seekers in the Age of Reason, featured in the previous posting) appeared last year, but since I failed to note it and since we’ve just highlighted the Gothic Imagination and Witches, it seemed like a good time to backtrack.

And, I would note, after so many events to mark the Hanoverian anniversary, Coronation Day is finally here: George I was crowned at Westminster Abbey on 20 October 1714. –CH

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From Yale UP:

Paul Kléber Monod, Solomon’s Secret Arts: The Occult in the Age of Enlightenment (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 440 pages, ISBN: 978-0300123586, $50.

The late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are known as the Age of Enlightenment, a time of science and reason. But in this illuminating book, Paul Monod reveals the surprising extent to which Newton, Boyle, Locke, and other giants of rational thought and empiricism also embraced the spiritual, the magical, and the occult. Although public acceptance of occult and magical practices waxed and waned during this period they survived underground, experiencing a considerable revival in the mid-eighteenth century with the rise of new anti-establishment religious denominations. The occult spilled over into politics with the radicalism of the French Revolution and into literature in early Romanticism. Even when official disapproval was at its strongest, the evidence points to a growing audience for occult publications as well as to subversive popular enthusiasm. Ultimately, finds Monod, the occult was not discarded in favor of ‘reason’ but was incorporated into new forms of learning. In that sense, the occult is part of the modern world, not simply a relic of an unenlightened past, and is still with us today.

The late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are known as the Age of Enlightenment, a time of science and reason. But in this illuminating book, Paul Monod reveals the surprising extent to which Newton, Boyle, Locke, and other giants of rational thought and empiricism also embraced the spiritual, the magical, and the occult. Although public acceptance of occult and magical practices waxed and waned during this period they survived underground, experiencing a considerable revival in the mid-eighteenth century with the rise of new anti-establishment religious denominations. The occult spilled over into politics with the radicalism of the French Revolution and into literature in early Romanticism. Even when official disapproval was at its strongest, the evidence points to a growing audience for occult publications as well as to subversive popular enthusiasm. Ultimately, finds Monod, the occult was not discarded in favor of ‘reason’ but was incorporated into new forms of learning. In that sense, the occult is part of the modern world, not simply a relic of an unenlightened past, and is still with us today.

Paul Monod is A. Barton Hepburn Professor of History at Middlebury College. He lives in Weybridge, Vermont.

New Book | The Dark Side of the Enlightenment

From Norton:

John V. Fleming, The Dark Side of the Enlightenment: Wizards, Alchemists, and Spiritual Seekers in the Age of Reason (New York: W. W. Norton, 2013), 432 pages, ISBN: 978-0393079463, $28.

In The Dark Side of the Enlightenment, John V. Fleming shows how the impulses of the European Enlightenment—generally associated with great strides in the liberation of human thought from superstition and traditional religion—were challenged by tenacious religious ideas or channeled into the ‘darker’ pursuits of the esoteric and the occult. His engaging topics include the stubborn survival of the miraculous, the Enlightenment roles of Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry, and the widespread pursuit of magic and alchemy.

In The Dark Side of the Enlightenment, John V. Fleming shows how the impulses of the European Enlightenment—generally associated with great strides in the liberation of human thought from superstition and traditional religion—were challenged by tenacious religious ideas or channeled into the ‘darker’ pursuits of the esoteric and the occult. His engaging topics include the stubborn survival of the miraculous, the Enlightenment roles of Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry, and the widespread pursuit of magic and alchemy.

Though we tend not to associate what was once called alchemy with what we now call chemistry, Fleming shows that the difference is merely one of linguistic modernization. Alchemy was once the chemistry, of Arabic derivation, and its practitioners were among the principal scientists and physicians of their ages. No point is more important for understanding the strange and fascinating figures in this book than the prestige of alchemy among the learned men of the age.

Fleming follows some of these complexities and contradictions of the ‘Age of Lights’ into the biographies of two of its extraordinary offspring. The first is the controversial wizard known as Count Cagliostro, the ‘Egyptian’ freemason, unconventional healer, and alchemist known most infamously for his ambiguous association with the Affair of the Diamond Necklace, which history has viewed as among the possible harbingers of the French Revolution and a major contributing factor in the growing unpopularity of Marie Antoinette. Fleming also reviews the career of Julie de Krüdener, the sentimental novelist, Pietist preacher, and political mystic who would later become notorious as a prophet.

Impressively researched and wonderfully erudite, this rich narrative history sheds light on some lesser-known mental extravagances and beliefs of the Enlightenment era and brings to life some of the most extraordinary characters ever encountered either in history or fiction.

John V. Fleming is the Louis W. Fairchild, ’24 Professor of English and Professor of Comparative Literature emeritus at Princeton University, where he taught for forty years before retiring in 2006. Fleming graduated from Sewanee (the University of the South) in 1958, before spending three years in Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. After taking his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1963, he taught for two years at the University of Wisconsin (Madison). He has published widely in the fields of medieval literature, art history, and religious history.

Exhibition | Witches and Wicked Bodies

I noted this exhibition last year when it went on display in Scotland, but I didn’t realize it would also be on view in London. The description on The British Museum’s website provides additional information. I saw the exhibition Friday evening, and I think it’s fabulous (a nice complement to the British Library’s exhibition Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination, even as they do very different things). There are stunning eighteenth-century images, and the period anchors the show more than the descriptions might suggest (including gorgeous prints after Salvator Rosa). –CH

From The British Museum:

Witches and Wicked Bodies

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, 27 July — 3 November 2013

The British Museum, London, 25 September 2014 — 11 January 2015

This exhibition will examine the portrayal of witches and witchcraft in art from the Renaissance to the end of the 19th century. It will feature prints and drawings by artists including Dürer, Goya, Delacroix, Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, alongside classical Greek vessels and Renaissance maiolica.

Efforts to understand and interpret seemingly malevolent deeds—as well apportion blame for them and elicit confessions through hideous acts of torture—have had a place in society since classical antiquity and Biblical times. Men, women and children have all been accused of sorcery. The magus, or wise practitioner of ‘natural magic’ or occult ‘sciences’, has traditionally been male, but the majority of those accused and punished for witchcraft, especially since the Reformation, have been women. They are shown as monstrous hags with devil-worshipping followers. They represent an inversion of a well-ordered society and the natural world.

The focus of the exhibition is on prints and drawings from the British Museum’s collection, alongside a few loans from the V&A, the Ashmolean, Tate Britain and the British Library. Witches fly on broomsticks or backwards on dragons or beasts, as in Albrecht Dürer’s Witch Riding backwards on a Goat of 1501, or Hans Baldung’s Witches’ Sabbath from 1510. They are often depicted within cave-like kitchens surrounded by demons, performing evil spells, or raising the dead within magic circles, as in the powerful work of Salvator Rosa, Jacques de Gheyn and Jan van der Velde.

Francisco de Goya turned the subject of witches into an art form all of its own, whereby grotesque women conducting hideous activities on animals and children were represented in strikingly beautiful aquatint etchings. Goya used them as a way of satirising divisive social, political and religious issues of his day. Witches were also shown as bewitching seductresses intent on ensnaring their male victims, seen in the wonderful etching by Giovanni Battista Castiglione of Circe, who turned Odysseus’s companions into beasts.

During the Romantic period, Henry Fuseli’s Weird Sisters from Macbeth influenced generations of theatre-goers, and illustrations of Goethe’s Faust were popularised by Eugène Delacroix. By the end of the 19th century, hideous old hags with distended breasts and snakes for hair were mostly replaced by sexualised and mysteriously exotic sirens of feminine evil, seen in the exhibition in the work of Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Odilon Redon.

The exhibition includes several classical Greek vessels and examples of Renaissance maiolica to emphasise the importance of the subject in the decorative arts.

Exhibition | Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the publication of Horace Walpole’s ’s The Castle of Otranto, and the British Library celebrates with an exhibition exploring the the relationship between the Gothic and the British imagination up to the present. The wall colors are from Farrow & Ball, with Lulworth Blue (No. 89) providing the backdrops for most of the Walpole material at the beginning of the exhibition, along with Great White (No. 2006), before things go really dark with Pitch Black (No. 256) and Rectory Red (No. 217). Of course, there’s Rectory Red in this show.

From the BL:

Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination

British Library, London, 3 October 2014 — 20 January 2015

Curated by Tim Pye

John Giles Eccardt, Portrait of Horace Walpole, 1754 (London: National Portrait Gallery)

Two hundred rare objects trace 250 years of the Gothic tradition, exploring our enduring fascination with the mysterious, the terrifying and the macabre. From Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker to Stanley Kubrick and Alexander McQueen, via posters, books, film and even a vampire-slaying kit, experience the dark shadow the Gothic imagination has cast across film, art, music, fashion, architecture and our daily lives.

Beginning with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, Gothic literature challenged the moral certainties of the 18th century. By exploring the dark romance of the medieval past with its castles and abbeys, its wild landscapes and fascination with the supernatural, Gothic writers placed imagination firmly at the heart of their work—and our culture. Iconic works, such as handwritten drafts of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the modern horrors of Clive Barker’s Hellraiser, and the popular Twilight series, highlight how contemporary fears have been addressed by generation after generation.

Dozens of press images can be found here»

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Dale Townsend, ed., Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination (London: The British Library, 2014), 224 pages, softcover, ISBN: 978-0712357913, £25 / hardcover, ISBN: 978-0712357555, £35.

The Gothic imagination, that dark predilection for horrors and terrors, spectres and sprites, occupies a prominent place in contemporary Western culture. First given fictional expression in Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto of 1764, the Gothic mode has continued to haunt literature, fine art, music, film and fashion ever since its heyday in Britain in the 1790s. Terror and Wonder, which accompanies a major exhibition at the British Library, is a collection of essays that trace the numerous meanings and manifestations of the Gothic across time, tracking its prominent shifts and mutations from its eighteenth-century origins, through the Victorian period, and into the present day. Edited and introduced by Dale Townshend, and consisting of original contributions by Nick Groom, Angela Wright, Alexandra Warwick, Andrew Smith, Lucie Armitt and Catherine Spooner, Terror and Wonder provides a compelling and comprehensive overview of the Gothic imagination over the past 250 years

The Gothic imagination, that dark predilection for horrors and terrors, spectres and sprites, occupies a prominent place in contemporary Western culture. First given fictional expression in Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto of 1764, the Gothic mode has continued to haunt literature, fine art, music, film and fashion ever since its heyday in Britain in the 1790s. Terror and Wonder, which accompanies a major exhibition at the British Library, is a collection of essays that trace the numerous meanings and manifestations of the Gothic across time, tracking its prominent shifts and mutations from its eighteenth-century origins, through the Victorian period, and into the present day. Edited and introduced by Dale Townshend, and consisting of original contributions by Nick Groom, Angela Wright, Alexandra Warwick, Andrew Smith, Lucie Armitt and Catherine Spooner, Terror and Wonder provides a compelling and comprehensive overview of the Gothic imagination over the past 250 years

Dale Townshend is Senior Lecturer in Gothic and Romantic Literature at the University of Stirling, Scotland. His most recent publications include The Gothic World (with Glennis Byron; Routledge, 2014) and Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic (with Angela Wright; Cambridge University Press, 2014).

C O N T E N T S

Dale Townshend, Introduction

Nick Groom, Gothic Antiquity: From the Sack of Rome to The Castle of Otranto

Angela Wright, Gothic, 1764–1820

Alexandra Warwick, Gothic, 1820–1880

Andrew Smith, Gothic and the Victorian Fin de siècle, 1880–1900

Lucie Armitt, Twentieth-Century Gothic

Catherine Spooner, Twenty-First-Century Gothic

Martin Parr, Photographing Goths: Martin Parr at the Whitby Goth Weekend

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the exhibition press release (2 October 2014). . .

Terror and Wonder: The Gothic Imagination opens at the British Library exploring Gothic culture’s roots in British literature and celebrating 250 years since the publication of the first Gothic novel.

Tintern Abbey, watercolour, 1812 (London: British Library)

Alongside the manuscripts of classic novels such as Frankenstein, Dracula, and Jane Eyre, the exhibition brings the dark and macabre to life with artefacts, old and new. Highlights of the exhibition include a vampire slaying kit and 18th- and 19th-century Gothic fashions, as well as one of Alexander McQueen’s iconic catwalk creations. Also on display is a model of the Wallace and Gromit Were-Rabbit, showing how Gothic literature has inspired varied and colourful aspects of popular culture in exciting ways over centuries.

Celebrating how British writers have pioneered the genre, Terror and Wonder takes the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, and exhibits treasures from the Library’s collections to carry the story forwards to the present day. Eminent authors over the last 250 years, including William Blake, Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, Charles Dickens, the Brontës, Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, MR James, Mervyn Peake, Angela Carter and Neil Gaiman, underpin the exhibition’s exploration of how Gothic fiction has evolved and influenced film, fashion, music, art and the Goth subculture.

An early illustration of a ‘wicker man’ from Nathaniel Spencer’s The Complete English Traveller (1771)

Lead curator of the exhibition, Tim Pye, says: “Gothic is one the most popular and influential modes of literature and I’m delighted that Terror and Wonder is celebrating its rich 250 year history. The exhibition features an amazingly wide range of material, from stunningly beautiful medieval artefacts to vinyl records from the early Goth music scene, so there is truly something for everyone.”

From Nosferatu to the most recent zombie thrillers, the exhibition uses movie clips, film posters, costume designs and props to show how Gothic themes and literature have been adapted for stage and screen, propelling characters like Dracula, Jekyll and Hyde and Frankenstein’s monster to mainstream fame. Exciting exhibits on loan to the Library include Clive Barker’s original film script and sketches for Hellraiser, as well as Stanley Kubrick’s annotated typescript of The Shining.

Showing how Gothic fiction has inspired great art, the exhibition features fine paintings and prints, such as Henry Fuseli’s Hamlet, Prince of Denmark and Nathaniel Grogan’s Lady Blanche Crosses the Ravine, a scene taken directly from the Queen of Terror Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho. These classic images precede dramatic contemporary artworks, such as Jake and Dinos Chapman’s series Exquisite Corpse, showing how the dark and gruesome still inspire today’s artists.

Celebrating the British Goth scene, we are delighted to reveal a brand new series of photographs of the Whitby Goth Weekend by the award-winning photographer Martin Parr. Commissioned specially for this exhibition, the photographs take a candid look at the biannual event, which takes place in the town famously featured in Dracula, capturing its diversity and energy.

Earlier this year the Library announced that we are putting our literary treasures online for the world to see with a new website, Discovering Literature. Many of the Gothic literary greats featuring in the exhibition, including the Brontës, Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins, can be explored amongst the Romantic and Victorian literature now available online.

The Library has partnered with BBC Two and BBC Four to celebrate all things Gothic this autumn with a new season of programmes exploring the literature, architecture, music and artworks that have taken such a prominent place in British culture.

A host of famous literary faces will look back on Frankenstein’s creation in A Dark and Stormy Night: When Horror Was Born, while in The Art of Gothic: Britain’s Midnight Hour Andrew Graham-Dixon looks back at how Victorian Britain turned to the past for inspiration to create some of Britain’s most famous artworks and buildings. In God’s own Architects: The First Gothic Age, Dr Janina Ramirez looks at Perpendicular Gothic, Britain’s first cultural style and Dan Cruickshank looks back at Gothic architecture’s most influential family in A Gothic Dynasty: A Victorian Tale of Triumph and Tragedy. BBC Four delves into the archives uncovering classic performances from Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bauhaus, The Cure, Sisters of Mercy, The Mission and more in Goth at the BBC.

For the second year running the Library, GameCity and Crytek are running an exciting video game competition, Off the Map, this time with a Gothic edge. Following last year’s winners, who recreated London before the Great Fire, this year entrants will use ruined abbeys, the town of Whitby or Edgar Allan Poe as inspiration for a brand new interactive game.

A wide range of literary, film and music events will accompany the exhibition, with speakers including writers Susan Hill, Sarah Waters, Audrey Niffenegger and Kate Mosse, actor Reece Shearsmith, comedian Stewart Lee and musician Brian May.

Exhibition | The Sparkling Soul of Terracotta

Press release (distributed by Cawdell Douglas), via Art Daily (the particularly handsome 124-page catalogue is available for free download as PDF file here).

The Sparkling Soul of Terracotta: 16th to 19th Centuries

Caiati & Gallo Gallery, Milan, 9 October – 8 November 2014

Caiati & Gallo Gallery is paying tribute to terracotta with an important exhibition entitled The Sparkling Soul of Terracotta: Exploring the Vibrant Intensity of Sculpture from the 16th to 19th Centuries. The exhibition centres around fifteen works of art which represent the peak of their particular era. These important works have been tracked down through extensive research and collaboration by a team of leading scholars. Each piece has been selected for its unique contribution to the history of art.

Caiati & Gallo Gallery is paying tribute to terracotta with an important exhibition entitled The Sparkling Soul of Terracotta: Exploring the Vibrant Intensity of Sculpture from the 16th to 19th Centuries. The exhibition centres around fifteen works of art which represent the peak of their particular era. These important works have been tracked down through extensive research and collaboration by a team of leading scholars. Each piece has been selected for its unique contribution to the history of art.

One of the most touching examples is the late-baroque Lombard group of Jupiter and Semele by the Milanese sculptor Carlo Francesco Mellone. It represents Jupiter meeting his lover Semele, who has a small cherub at her side. A second cherub who has since lost both arms completes the scene. The figures rest on a rectangular base, possibly alluding to the bed in which their adultery was committed. Mellone’s figures are light and full of movement. Semele’s facial features are typical of the sculptor’s work: the delicate oval shape, small mouth and large eyelids exemplify a style repeated in numerous

other works.

René Frémin (1672–1744), Allegory of America. This statue is of a girl crowned by a full head of feathers in a long dress, her legs covered in a short irregularly-shaped tunic. The delicacy of her affected gestures, her flowing drapes and the square base bring to mind the gardens of the Royal Palace at La Granja of Sant’ Ildefonso, the summer residence of the King of Spain. This enables us to place the statue within the works of Frémin since he was responsible for the decoration of the palace from 1721 onwards. He was Louis XIV’s favourite sculptor and entered the French Academy in 1696.

Ignazio (1724–1793) and Filippo Collino (1737–1800), Pair of statues. Defence of Glory and Strength by the two brothers who were among the most important sculptors in Piedmont in the second half of the eighteenth century. Defence of Glory. This light, standing female figure is particularly refined. Her beautiful features are highlighted by her full head of hair gathered behind her neck. Great emphasis is given to her lithe body that is accentuated by a dress which mischievously clings to her body. A soft cloak with folds and pleats hangs down to her feet. The presence of a sword and a laurel branch with berries held between the woman’s fingers suggests the figure is an allegorical personification of the Defence of Glory. Strength. The figure in this work holds a baton in her hands with an oval shield bearing a relief of a lion attacking a wild boar. The woman’s features are drawn from the classical model of female beauty. Created as part of a pair with the Defence of Glory, the work is both refined and cultivated in terms of style, bearing considerable similarity to the French Rococo, late-baroque Roman and Tuscan classicism and the eclectic styles of mid eighteenth-century Venetian sculpture.

Jean Del Cour (1627–1707), Saint John. The most important Flemish sculptor of his time, Del Cour sculpted in marble, bronze, and wood. He was influenced by French and Flemish styles as well as by Bernini who he had met and visited in Rome during one of his long stays in the Eternal City. Del Cour’s Bernini-esque interpretations were both brilliant and original thanks to his ability to present the modernity of his epoch and thus translate passion, love, sensuality, and mysticism into dynamism, strength, and elegance.

Antonio Begarelli (Modena 1499–1565) Saint with Book (Saint Justine?). Little is known of the life of Begarelli before 1522, when, as a young man (in those days, under twenty-five was considered very young), he burst onto Modena’s artistic scene. Without receiving any commission, he undertook a large statue in terracotta, the Madonna di Piazza that he offered for free to the city. Today, it is kept at Modena’s Museo Civico. The statue was hugely popular and eventually earned him the position of Modena’s official artist.

Antonio Calegari (Brescia 1699–1777) Madonna with Child. Having trained with his father, Sante, Calegari drew from the seafaring traditions of Venice and exploited the dynamism, chiaroscuro, and vivacity that characterised his better works. In later years, his work enjoyed brilliant Rococo influences in perfect harmony with the latest styles in Venice and, above all, the work of Giambattista Tiepolo. It is to this last phase, from the mid-1750s to the early-1760s, that this work belongs.

Guido Reni, (Bologna 1575–1642) from a model of the Bust of Seneca. This dynamic terracotta sculpture of the ancient philosopher has been perfectly conserved, so that the exceptional modelling of the clay is still in evidence. It can be compared to at least seven versions in terracotta, bronze, plaster, and stone, all of which are replicas of Reni’s Seneca. According to Carlo Cesare Malvasia, the original was a terracotta relief head. In his thorough biography of Reni, contained in his celebrated work Felsina Pittrice (1678), Malvasia exalts Reni as the quintessential artist of seventeenth-century Bologna. Of the sculpted copies now known of the powerful head, only the two terracotta versions and this unseen work, could truly claim attribution to the master.

Lorenzo Sarti ( ?) (documented in Emilia and Veneto from 1722 to 1747) The Trinity with the Guardian Angel and Saints Filippo Benizzi, Francesco da Paola, Filippo Neri and Carlo Borromeo and The Blessed Virgin between Saint Caterina d’Alessandria and Christ carrying the Cross, with Saints Augustine, Domenic and Thomas Aquinas. Having undergone recent restoration, these two important terracotta high reliefs demonstrate all the depth and detail of their original modelling. Though the provenance and collection histories are unknown, examination suggests that they are from a school which originated within the walls of Bologna. This school was formed under the aegis of Giuseppe Maria Mazza and was then led by his pupil Angelo Gabriello Pi . Sarti was one of his best pupils. The two rectangular reliefs which should be regarded as pendants, are of very similar dimensions and format. The compositions both have a pyramidal form, with the holy groups placed at the apex. The lower part is an ordered and symmetrical arrangement of saints who appear in hierachical order.

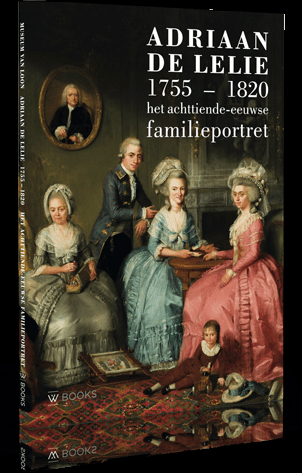

Exhibition | Adriaan de Lelie and the Family Portrait

From the Museum Van Loon (with thanks to Hélène Bremer for noting it). . .

Adriaan de Lelie and the Eighteenth-Century Family Portrait

Museum Van Loon, Amsterdam, 17 October 2014 — 19 January 2015

From 17 October 2014 Museum Van Loon will show works by Adriaan de Lelie (1755–1820). It is the first time that so much of De Lelie’s œuvre will be on view to the public. Most of the paintings are from private collections. Next to paintings by De Lelie, family portraits by famous contemporaries like Tischbein, Regters, Laquy and Quinkhard are on display. The thirty paintings on show give a perfect reflection of family bliss and the lavish interiors of the 18th century.

Although little has been published about De Lelie, he is without doubt one of the most important portrait painters of his time. He was born in Tilburg, and after having studied in Antwerp and Düsseldorf, he settled in Amsterdam where he quickly integrated in the upper classes. With his keen eye for detail, refined palette, and smooth hand he was a successful portraitist. Governors, bankers, notaries, officers, professors, and wealthy merchants had themselves painted by him. Thus De Lelie literally gave face to Amsterdam at the turn of the century.

As a family home, Museum Van Loon is the place for showing family portraits. With this exhibition it intends to disclose its own 18th-century collection of paintings and to offer the public the unique opportunity to view the oeuvre of De Lelie and his contemporaries in the house of one of his large commissioners. For visitors the historic perspective is strengthened by the connection between the paintings, furniture, tapestry and carpets in the rooms as one will see one’s immediate surroundings in the museum reflected in the 18th-century interiors in the paintings.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From W Books:

Josephina de Fouw, Adriaan de Lelie (1755–1820) en het achttiende-eeuwse familieportret (Zwolle: W Books, 2014), 64 pages, ISBN: 978-9462580398, €15.

Adriaan de Lelie behoort zonder meer tot de belangrijkste portretschilders van zijn tijd. Zijn wieg stond in Tilburg en na een studietijd in Antwerpen en Düsseldorf vestigde hij zich definitief in Amsterdam. Daar wist hij al snel door te dringen in de kringen van de gegoede burgerij. Met zijn oog voor detail en verfijnde palet was hij een veelgevraagd portrettist. Notabelen, bankiers, notarissen, officieren, hoogleraren en vermogende koopmannen: allen lieten zich door de schilder vereeuwigen. De Lelie heeft zo letterlijk een gezicht gegeven aan het Amsterdam van rond de eeuwwisseling.

Adriaan de Lelie behoort zonder meer tot de belangrijkste portretschilders van zijn tijd. Zijn wieg stond in Tilburg en na een studietijd in Antwerpen en Düsseldorf vestigde hij zich definitief in Amsterdam. Daar wist hij al snel door te dringen in de kringen van de gegoede burgerij. Met zijn oog voor detail en verfijnde palet was hij een veelgevraagd portrettist. Notabelen, bankiers, notarissen, officieren, hoogleraren en vermogende koopmannen: allen lieten zich door de schilder vereeuwigen. De Lelie heeft zo letterlijk een gezicht gegeven aan het Amsterdam van rond de eeuwwisseling.

In deze eerste publicatie gewijd aan De Lelie wordt een beeld geschetst van deze portretten en wordt ingegaan op de karakteristieken van zijn familieportretten. Ook wordt zijn werk vergeleken met voorgangers en tijdgenoten, zoals Tibout Regters, Tischbein en Laquy.

Call for Articles | Anthology: On the Politics of Ugliness

As noted at H-ArtHist:

Anthology: On the Politics of Ugliness

Chapter proposals due by 15 January 2015

Ugliness is a pejorative marker for bodies, things, and feelings that fall beyond or outside the limits of acceptability. Ugliness has long been indirectly deployed in order to mark, collect, and exclude that which is determined to be aesthetically intolerable (Garland-Thomson; Grealy; Schweik), disgusting (Meagher), dirty (Douglas), abject (Kristeva), monstrous (Braidotti; Haraway; Rai & Puar; Schildrick; Sharpe), revolting (Lebesco), grotesque (Russo), or even simply plain and unaltered (Bartky; Bordo; Morgan; Wolf). While aesthetically ugliness has been positioned both against beauty and as a distinct category for art and art-making (Adorno; Ranciere), there has been little sustained engagement with the ways that ugliness operates alongside identities, bodies, intimacies, practices, and spaces (exceptions include Danticat; Kincaid; Athanassoglou-Kallmyer). Part of the reason for this absence might be that ugliness is at once too broad and too diffuse, serving, as art historian Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer has pointed out, as “an all-purpose repository for everything that [does] not quite fit,” a marker of “mundane reality, the irrational, evil, disorder, dissonance, irregularity, excess, deformity, the marginal” (281).

A repository for many socio-cultural feelings and attitudes, ugliness operates in ways that have dangerous and deadly consequences for bodies and those who inhabit them. When a body is labeled or understood as ‘ugly’, it is subsequently positioned as up for expunging, destruction, and affectively motivated terror (Fanon). For example, the ‘ugly laws’ of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America demonstrate the visceral discomfort that ‘ugly’ bodies evoke, justifying their exclusion from public spaces on account of their ‘polluting’ effects (Schweik). This demarcation of ugliness is inextricably bound with taken-for-granted ethical, epistemological, and ontological assumptions about the value of bodies. Further, ugliness is infused with dominant discourses of ability, race, heterosexuality, gender, body size, health, and age. At the level of ideas, relations and institutions, deployments of ugliness can have lethal effects on a body’s horizons and the possibilities for visibility, intimacy, and thick life.

On the Politics of Ugliness seeks to provide the first anthology that centralizes ugliness as a political category. It explores the various ways in which ugliness is deployed against those whose bodies, habits, gestures, feelings, expressions, or ways of being deviate from social norms. It argues that ugliness is politicalin at least two ways: (1) it denotes inequalities and hierarchies, often serving as a repository for all that is ‘other’; and (2) it is contingent and relational, taking shape through the comparison and evaluation of bodies. This collection asserts that it is only in facing ugliness as a political category that we can agitate routinely harmful ways of seeing, understanding and relating.

We are seeking an array of contributions that will center the politics of ugliness as it relates to bodies, feelings, gestures, habits, things, spaces, sounds, intimacies and their operations alongside ability, race, gender, class, sexuality, body size, age, health, or animality. Specifically, we invite submissions of academic papers; however, we will also consider art-based work, memoirs, cultural scholars, writers, and artists. We welcome approaches informed by (but not limited to) critical disability studies, critical race and postcolonial studies, feminist theory, literary theory, art history, cultural studies, queer and sexuality studies, science and technology studies, critical psychology, environmental studies, musicology, and performance studies.

Submissions should engage with the politics of ugliness. Topics of inquiry may include

• interrogations of ugliness as violence against bodies

• the ethics of engaging with ugliness

• feminist explorations of ugliness, ‘ugly’ engagements with feminism

• ugly methodologies, reading practices, and modes of inquiry

• representations of ugliness, ‘ugly’ bodies, body parts, and ‘ugly’ behaviors

• phenomenological encounters with ugliness: feeling ugly, being ‘ugly’, embodying ugliness

• ugly intimacies, feelings, and dispositions (e.g., Ngai; Sharpe)

• genealogies, archives, temporalities, and histories of ugliness

• the fashionizing of ugliness, ugly fashion

• ugly development practices, environmental ugliness

• visual, sensorial, and tactile pollution in relation to spaces and geographies

• theoretical considerations of ugliness as a political category

• reclamations and tactical repositionings of ugliness (e.g., Eileraas)

The deadline for chapter proposals (maximum of 500 words) is 15 January 2015. Please forward proposals or questions to Ela Przybylo (przybylo@yorku.ca) and Sara Rodrigues (sararod@yorku.ca) with the subject heading “On the Politics of Ugliness.”

Exhibition | Alexander, Napoleon, and Joséphine

Opening next spring at the Hermitage Amsterdam:

Alexander, Napoleon, and Joséphine

Hermitage Amsterdam, 28 March — 18 October 2015

Anonymous, after Gioacchino Serangeli, Napoleon and Alexander I Bid Farewell after the Peace of Tilsit (Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)

It is October 1812. Napoleon and his troops are leaving Moscow. The French armies’ long advance has been checked: Tsar Alexander I has refused to surrender to Napoleon. The inhabitants of Moscow have fled and set the city alight. The army can go no further without supplies. The retreat is disastrous. Napoleon loses half a million men to freezing temperatures and combat. This is a turning point in history, the prelude to Napoleon’s ultimate defeat at Waterloo.

This exhibition brings to life the battle waged by two emperors on the turbulent European stage. From their initial friendship, their meeting on the raft at Tilsit and a fragile peace to the great battles and the fire of Moscow. One woman plays a pivotal role in both their lives: Joséphine de Beauharnais. Her collection from Château de Malmaison eventually ended up in the

Winter Palace in St Petersburg.

Symposium | The Century of Taste: Art in the Age of Enlightenment

As noted at H-ArtHist:

Das Jahrhundert des Geschmacks: Kunst im Zeitalter der Aufklärung

Historischer Saal der Ravensberger Spinnerei, Ravensberger Park, Bielefeld, 28 November 2014

Eine Veranstaltung der Kunstsammlung Rudolf-August Oetker GmbH, des Museum Huelsmann und der Professur für Kunstgeschichte der Universität Bielefeld. Konzeption: Monika Bachtler, Johannes Grave und Hildegard Wiewelhove

Das 18. Jahrhundert hat in vielerlei Hinsicht den modernen Kunstbegriff geprägt, der—ungeachtet aller Zuspitzungen und Infragestellungen—noch bis in unsere Gegenwart nachwirkt. Was wir unter Kunst verstehen, aber auch wie wir mit Kunst umgehen und sie in unser soziales Leben einbinden, ist erheblich durch Entwicklungen beeinflusst worden, die im 18. Jahrhundert ihren Anfang genommen haben. In das Jahrhundert der Aufklärung fallen die Etablierung regelmäßiger Kunstausstellungen, die Entstehung der Kunstkritik und die zunehmende Verbreitung einer bürgerlich geprägten Sammelkultur ebenso wie die Begründung der Ästhetik als einer philosophischen Disziplin, die der Sinnlichkeit eine eigene Erkenntniskraft zumisst. All diese Entwicklungen haben ihrerseits in ohem Maße auf die Künstler und ihre Werke zurückgewirkt. In exemplarischer Weise lässt sich in dieser Zeit daher beobachten, wie sich die Kunstproduktion, der Umgang mit Kunst und das Nachdenken über das Ästhetische wechselseitig beeinflussen.

Anlässlich der Ausstellung Wie es uns gefällt. Kostbarkeiten aus der Sammlung Rudolf-August Oetker, die das 18. Jahrhundert mit ausgewählten Werken der Kunst und des Kunsthandwerks vor Augen führt, soll das Symposium Schlaglichter auf die Kunst und ästhetische Kultur dieser Zeit werfen. In sechs Vorträgen wird sich die Veranstaltung sowohl exemplarischen Werken oder Werkgruppen als auch dem kulturellen Kontext zuwenden, um zu einem besseren Verständnis des Jahrhunderts des Geschmacks beizutragen. Dabei könnte sich erweisen, dass die durchaus spielerischen Formen, in denen im 18. Jahrhundert Kunst und Leben immer wieder neu zueinander ins Verhältnis gesetzt wurden, von überraschender Aktualität sind.

Tagungsgebühr: 20€; ermäßigt für Studierende und Auszubildende: 10€. Anmeldung unter (0521) 51-3767 oder info@museumhuelsmann.de

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

P R O G R A M M

10.00 Dr. Monika Bachtler (Kunstsammlung Rudolf-August Oetker GmbH) und Prof. Dr. Hildegard Wiewelhove (Museum Huelsmann), Begrüßung

10.15 Prof. Dr. Johannes Grave (Universität Bielefeld), Einführung

10.30 Dr. Christoph Martin Vogtherr (Wallace Collection London), Niederländische und französische Malerei im Paris des 18. Jahrhunderts

11.30 Dr. Ulrike Grimm (Karlsruhe), Ein Schloss, “in welchem guter Geschmack mehr Gewicht besitzt als äußere Pracht”. Zur Residenz der Caroline Luise von Baden in Karlsruhe

12.30 Mittagspause mit kleinem Imbiss

13.30 Prof. Dr. Anna Zika (Fachhochschule Bielefeld), … und nur das Natürliche ist schön. Modediskurse in deutschsprachigen Journalen des späten 18. Jahrhunderts

14.30 Prof. Dr. Reinhard Wegner (Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena), Wie kommt die Farbe ins Bild? Newtons Lichttheorie und die Schönen Künste

15.30 Kaffeepause

16.00 Prof. Dr. Beate Söntgen (Leuphana Universität, Lüneburg), Stiller Austausch. Chardins Formen der Kommunikation

17.00 Prof. Dr. Thomas Kirchner (Deutsches Forum für Kunstgeschichte, Paris), Die Französische Revolution und die Demokratisierung der Kunst

18.00 Abschlussdiskussion

leave a comment