Call for Papers | Temporal Ecologies in Art and Nature, ca. 1800

From ArtHist.net:

Sympoiesis: Temporal Ecologies in Art and Nature, ca. 1800

Sympoiesis: Zeit-Ökologien in Kunst und Natur um 1800

Erbacher Hof, Mainz, 30 September — 2 October 2026

Proposals due by 15 March 2026

Second annual conference of the Mini-Graduate College Die ästhetischen Erfindungen der Ökologie um 1800, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

Between geological deep time and the fleetingness of a single breath, between the slow erosion of coastlines and the periodic return of day and night, between vegetative growth, heartbeat, pulse, and meter, concepts of the natural unfold as constellations of heterogeneous temporal horizons. In works of art, these heterogeneous temporalities can be synchronized: the artwork then becomes a site of sympoiesis (Donna Haraway). This delineates a becoming-with in which biological growth processes, cyclical repetitions, and linear processes of decay are not merely represented but amalgamated into a new aesthetic temporality of the artwork itself. Mary Delaney serves as one example here. In her Paper Mosaiks, she makes collages out of real plant parts put together with colored paper. She presents bud and fruiting body, which are distinct developmental stages, simultaneously, thus transgressing the natural temporal order and creating a synchronicity of diachronic events.

The conference seeks to explore how artworks around 1800 work as cross-sections through heterogeneous temporal layers of the natural. The guiding concept of sympoiesis marks a shift in perspective. It does not pitch nature against art, nor does it denote environments as mere background. Instead, it highlights the cooperative production of vitality across different forms of knowledge and practice. At the center is thus a making-with, in which matter and materials, media, bodies, discourses, and practices enter into relation with one another. The chosen timeframe of around 1800—during which the interplay of natural philosophy, early biology, geology, aesthetics, poetics, and new musical temporal orders is especially prominent—lends itself to discussions of how vitality is both understood in the context of ecological relations and conceived as a temporally structured process of becoming.

A range of disciplinary approaches is welcome, including:

• Temporal ecologies in poetics and aesthetics, descriptions of nature, history of metaphors; meter, rhythm, repetition; temporal semantics of growth, transformation, threshold, crisis.

• Image-time and material time; montage/collage, series, study; landscape as a medium of deep time; visualizations of cycles, change, erosion; practices of collecting and classification as temporal orders.

• Beat, pulse, period, tempo as models of the living; bodily and affective temporalities; rhythmization, synchronization, and their disruptions; form as a temporal ecology (recurrence, variation, transition).

More broadly, the conference invites reflections on:

• Aesthetics and orders of temporality

• Temporal concepts within individual disciplines

• Knowledge and history, tense and development

• Phenomenologies of movement and transformation: how can growth and metamorphosis be narrated or visualized without freezing them in static representation?

• Rhythm and meter: where does “striated time” (meter, beat, measured time) encounter the ‘smooth time’ of organic flow? How do heartbeat, pulse, and breath relate to the musical period or poetic meter around 1800?

• Cycles and thresholds: how do art, literature, and music stage the transition from day to night, the change of seasons, or the stages of life? Do these works assert a harmonious synchronicity of the natural, or do they instead make visible the asynchronies and fractures within the temporal fabric?

The workshop will take place from 30 September to 2 October 2026 at the Erbacher Hof in Mainz. We invite interested scholars to submit abstracts in either German or English (maximum 300 words) for a 30-minute presentation, along with a short CV, to gregor.wedekind@uni-mainz.de and ctheisin@uni-mainz.de by 15 March 2026.

b i b l i o g r a p h y

• Bender, Niklas und Gisèle Séginger (Hg.): Biological Time, Historical Time: Transfers and Transformations in 19th-Century Literature, Leiden: Brill | Rodopi, 2018 (Faux Titre, 431).

• Gamper, Michael und Helmut Hühn (Hg.): Zeit der Darstellung. Ästhetische Eigenzeiten in Kunst, Literatur und Wissenschaft, Hannover: Wehrhahn, 2014.

• Geulen, Eva: „Zur Idee eines ‚innern geistigen Rhythmus‘ bei A.W. Schlegel“, in: Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie, Bd. 137, 2018, Sonderheft: August Wilhelm Schlegel und die Philologie, S. 211–224.

• Groves, Jason: »Goethe’s petrofiction. Reading the ›Wanderjahre‹ in the Anthropocene«, in: Goethe yearbook 22 (2015), p. 95–113.

• Gould, Stephen Jay: Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle: Myth and Metaphor in the Discovery of Geological Time, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987.

• Haraway, Donna: Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Durham: Duke University Press, 2016.

• Heringman, Noah: Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004.

• Honold, Alexander: Hölderlins Kalender. Astronomie und Revolution um 1800, Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2005.

• Kisser, Thomas (Hg.): Bild und Zeit. Temporalität in Kunst und Kunsttheorie seit 1800, München: Fink, 2011.

• Kling, Alexander und Jana Schuster (Hg.): Zeiten der Materie. Verflechtungen temporaler Existenzweisen in Wissenschaft und Literatur, 1770–1900, Hannover: Wehrhahn, 2021.

• Kugler, Lena: Die (Tiefen-)Zeit der Tiere. Zur Biodiversität modernen Zeitwissens, Göttingen: Wallstein, 2021.

• Mitchell, Timothy F.: Art and Science in German Landscape Painting, 1770–1840, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993 (Clarendon Studies in the History of Art, 11)

• Naumann, Barbara: Musikalisches Ideen-Instrument. Das Musikalische in Poetik und Sprachtheorie der Frühromantik, Stuttgart: Metzler, 1990.

• Oesterle, Ingrid: „‚Es ist an der Zeit!‘. Zur kulturellen Konstruktionsveränderung von Zeit gegen 1800“, in: Goethe und das Zeitalter der Romantik, hg. von Walter Hinderer, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2002, S. 91–119.

• Pause, Johannes und Tanja Prokić (Hg.): Zeiten der Natur: Konzeptionen der Tiefenzeit in der literarischen Moderne, Berlin und Heidelberg: Metzler, 2023.

• Ronzheimer, Elisa: Poetologien des Rhythmus um 1800. Metrum und Versform bei Klopstock, Hölderlin, Novalis, Tieck und Goethe, Berlin und Boston: De Gruyter, 2020.

• Rudwick, Martin J. S.: Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005.

• Schnyder, Peter: Erdgeschichten: Literatur und Geologie im langen 19. Jahrhundert, Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, 2020.

• Völker, Oliver: Langsame Katastrophen. Eine Poetik der Erdgeschichte. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2021.

• Voßkamp, Friederike: Im Wandel der Zeit. Die Darstellung der Vier Jahreszeiten in der Bildenden Kunst des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts, München und Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2023.

Call for Papers | Rethinking Familial Ties in the Visual Arts

From ArtHist.net:

(Re)alignment: Rethinking Familial Ties in the Visual Arts

National Gallery, London, 28 May 2026

Proposals due by 26 January 2026

Expanding our understanding of family, community, and what binds us together requires us to look beyond conventional definitions and documented histories. While official records like birth certificates offer us names, dates, and biological ties, they often fail to capture the emotional, cultural, and chosen connections that shape our identities and our sense of belonging. In a world where families are built not only by blood but by shared experience, mutual care, and collective memory, we must turn to other forms of expression to grasp the full picture.

Visual art—through painting, sculpture, photography, and other media— has long served as a powerful tool for representing and reimagining lineage and connection. These works can embody intimacy, inheritance, loss, and continuity in ways that resist formal categorisation. A family portrait may reveal who is physically present, but also who is emotionally central. A sculpture might abstractly represent generations, resilience, or migration. A photograph can capture unspoken dynamics: the touch of a hand, the distance between bodies, a gesture of affection or estrangement. Such representations invite us to ask: What does family look like when it isn’t constrained by official records? How do artists convey relationships rooted in mentorship, solidarity, or shared struggle? What visual metaphors such as threads, branches, shadows, echoes might they use to trace the invisible ties that bind?

Art can fill in the silences left by documentation. It allows us to see what a birth certificate cannot: the emotional textures of a relationship; the complexities of chosen family; and the legacies passed through gesture, tradition and story rather than DNA. By engaging with these visual representations, we expand our understanding of lineage not as a fixed biological chain, but as a living, evolving network of connection and meaning.

With this in mind, we welcome proposals for 20-minute papers from researchers, museum professionals, independent scholars, artist-practitioners, and postgraduate students. A potential outcome of the Colloquium will be the publication of selected papers in a special journal issue or edited volume. Papers may cover any period, geographic location, or medium of art.

Proposals will relate to the following themes:

• Ancestry: How are family lines and the dynamics of succession visually rendered in the arts? From large-scale family portraits to ornate illuminations of family trees, papers may focus on any one of the myriad ways in which ancestral ties have been made legible for public and private audiences. This may include shields, crests, trees and other symbols of family.

• Familial relationships: In what way are intimate family bonds portrayed in the visual arts? From siblings to parents, grandparents, and children, artists have long been drawn to depicting their own family members as well as undertaking commissions from patrons.

• Marriage: Portraits of betrothed or newly married couples may be a visual contract born of financial and social arrangements, romantic keepsake, or even a symbol of resistance. ‘Mystic marriages’ and mythical subjects further diversify the types of marriage we may see rendered in art.

• Inheritance and legacy: ‘Passing it on’ is a major part of family dynasties, particularly when it comes to hereditary titles and businesses. Visual art can be one means of not just establishing a line of inheritance but justifying and even fictionalising it.

• Blended and extended families: With the concept of a ‘nuclear’ family being a modern invention, family groups have long included members from outside the immediate or even blood related spheres. Step-relations, in-laws, wards, and charges have been integrated socially, legally, and visually into familial groups.

• Chosen family: Whether spiritual, such as in confraternities, convents, and other religious orders, or social, as is often found in the LGBTQ+ communities, depictions of chosen family might emphasise elements of support, belonging, or diversity.

Abstracts of no more than 300 words, along with a short biography (maximum 150 words), should be sent to maryanne.saunders@nationalgallery.org.uk by Monday, 26 January 2026. Please include your name, institutional affiliation (if applicable), preferred email, contact details, and any accessibility requirements. The conference organisers aim to let contributors know the outcome by mid-February. For further information, please view the colloquium website page.

Call for Articles | 2028 Issue of NKJ: The Artist’s Biography

From the Call for Papers:

The Artist’s Biography, 1400–Present

The Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art / Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ)

Volume 78 (2028)

Proposals due by 20 January 2026

In Rembrandt en de regels van de kunst (1961), Jan Emmens explored how, shortly after Rembrandt’s death, critics portrayed him as a Pictor vulgaris who preferred low-life company, fallen women, and ‘rough’ brushwork rather than classicism and fine painting. Such early criticism had a lasting impact on the Romantic idea of the artist as a misunderstood genius, influencing how Rembrandt and his artworks are perceived to this very day. Art historians also indulge in biographical manipulation, as Machiel Bosman shows in Rembrandts plan: De ware geschiedenis van zijn faillissement (2019). He scrutinizes archival material to expose the fragility of biographical claims built on incomplete or interpreted evidence while inviting reflection on how artist’s biographies are constructed, revised and contested. At the same time, new research on the artist, such as into Rembrandt’s relationship to the African community in Amsterdam (Ponte, 2020), has expanded our understanding of the artist as well as provided an entry into further understanding the Black experience in the Dutch Republic.

Biography, the containment and shaping of the unruly details of a human life into writing by another, has been central to art history since the appearance Vasari’s Lives of 1550. Authors of lives of Netherlandish artists, Karel van Mander, Joachim von Sandrart, Cornelis de Bie, Arnold Houbraken, Gerard de Lairesse, Filippo Baldinucci, Bainbrigg Buckeridge, Adriaan van der Willigen and Gerarda Hermina Marius, among others, all used biography to shape their accounts of art and included commentary on artists’ life choices alongside evaluations and descriptions of their art. Netherlandish art history from the start has thus been enmeshed with the personal identity of the artists who contributed to it, and biography, however problematic or challenging, has always been implicated in art theory and the analysis of art objects. As Nanette Salomon showed in “The Art Historical Canon: Sins of Omission” (1991), the selection of which artists’ lives to include and how they were written effectively shaped the canon of art history.

Of late, however, analysis of biographies has also served as an instrument to expand and critique the canon with particular significance for the study of Netherlandish art. Aspects neglected in biographies like artists’ gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and social class serve as a lens to ask new questions of familiar artworks or bring to the fore previously unknown or ignored artworks. Artists who did not appear in the standard biographies, especially women, are being rediscovered and given new ‘lives’. Additionally, biographical studies can also move into the direction of cancel culture. Comedian Hannah Gadsby, in her Netflix show Nanette (2017) and her exhibition, It’s Pablomatic (2023) at the Brooklyn Museum castigated Picasso’s misogyny. That same year, essayist Claire Dederer published Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma (2023), exploring the consequences of such feelings as described by Gadsby. What do we do with great art by bad people? How do we define what’s bad and how does this relate to the art?

NKJ 78 invites contributions exploring examples of entanglement between artwork and artist biography that will advance our understanding of the significance and theoretical implications of biographies of artists from the Low Countries (present-day Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands), 1400-present. We are also interested in papers that consider the definition of artists’ biographies and the potential value to art historical study for expanding it.

The call is open for studies on a range of matters related to artists’ biographies, including but not limited to:

• Historical attempts at separating artists from their art

• Identity as a driving artistic force

• Appropriation of an artist’s biography to political ends

• Biography in the quest for greater representation in scholarship and museum collections

• Biography in relation to notions of genius or greatness

• Relationship of artists’ biographies and the identity and status within culture

• Transgression/transgressive behavior as inherent artistic quality

• The relation between biography and cancel culture

• The power of time to change appreciation of artists’ conduct

• The relationship between individual artist’s identities and their broader societal contexts

• Differences in the form and function of artist biographies in northern and southern Europe

• Differences in the writing and perception of biographies between male and female artists

• How art theory shapes biography and vice versa

• Relating the life of the artist to the life of objects

• Portraits as a form of biography

• Artistic autobiography, including self portraits

• Expansion of the notion of biography

• Biography as a frame of cultural encounter, involving the locations, mobility and geographical affiliations of artists

• Biography and the development of art connoisseurship, including insights from technical and digital art history

• The literary tools of artists’ biographical writing: ekphrasis, anecdote, the moral exemplum

The NKJ is dedicated to a particular theme each year and promotes innovative scholarship and articles that employ a diversity of approaches to the study of Netherlandish art in its wider context. More information is available here. Contributions to the NKJ are limited to a maximum of 7500 words, excluding notes and bibliography. Following a peer review process and receipt of the complete text, the editorial board will make a final decision on the acceptance of a paper.

Please send a 500-word proposal and a short CV to all volume editors by 20 January 2026:

Lieke Wijnia, l.wijnia@rug.nl

Natasha Seaman, nseaman@ric.edu

Ingrid Vermeulen, i.r.vermeulen@vu.nl

Schedule

20 January 2026: Deadline for submission of abstracts

February 2026: Notifications about abstracts

1 November 2026: Submission of full articles for peer review

Early 2027: Decision on acceptance based on peer reviews

1 July 2027: Deadline revised articles

1 September 2027: Final articles, including illustrations & copyrights

Early 2028: Publication

Symposium | New Discoveries in Furniture and Historic Interiors

Left: Alexander Roslin, Portrait of Hedvig Elisabet Charlotta, Princess of Sweden, detail, 1775 (Nationalmuseum, Sweden). Center: André-Charles Boulle, Coffer-on-stand (Chatsworth House Trust). Right: Mirror shard cabinet, Apartment of Margravine Wilhelmine of Bayreuth, ca. 1750 (Old Palace of the Hermitage in Bayreuth; photo by Achim Bunz).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the reservation page at Eventbrite:

New Discoveries in Furniture and Historic Interiors

University of Buckingham, London Campus, 23 January 2026

Registration due by 19 January 2026

The Furniture History Society invites you to its eighth Early Career Research Symposium, to be held at the University of Buckingham’s London campus, 51 Gower Street, from 9.30am to 5pm on Friday, 23 January. Part of the Society’s Early Career Group (ECG) programme, the symposium features current research by emerging scholars in furniture history, the decorative arts, and historic interiors. The programme reflects the wide range of interests among early-career researchers, with speakers from Britain, Sweden, France, Italy, Germany, and the United States. The event is free to attend, but advance registration via Eventbrite is required by midnight (GMT) on Monday, 19 January. The limited number of places are allocated on a first-come, first-served basis. The symposium will be recorded and made available for one month to registered participants. Any enquiries about this event or the Early Career programme should be directed to grants@furniturehistorysociety.org.

The day is made possible thanks to the generous support of the University of Buckingham, the Della Howard Fund, and the Oliver Ford Trust.

p r e s e n t a t i o n s

• Mary Algood (V&A/RCD History of Design Programme, UK) — Makers of Funeral Furniture in 17th-Century England

• Tristan Fourmy (Institut National du Patrimoine, France) — Hercules in the Decorative Arts in 18th-Century France

• Laini Farrare (University of Delaware, USA) — Atlantic Mahogany: Enslavement, Labor, and the Early American Windsor Chair

• Francesco Montuori (European University Institute, Italy) — Beyond Chinoiserie: The Gabinetto di Porcellana and its Floor

• Anne Weiss (University of Cologne, Germany) — Status and Space: Dynastic References in the Furnishings of Wilhelmine von Bayreuth’s Apartments in the New Palace and Old Palace of the Hermitage in Bayreuth, 1735–1758

• Karolina Laszczukowska (University of Uppsala, Sweden) — The Material Hierarchies in the Furnishings and Interiors of the Private Apartments of Princess Sofia Magdalena and Duchess Hedvig Elisabet Charlotta at Stockholm Palace in 1766 and 1774

• Katherine Hardwick (Chatsworth House, UK) — Garrets Full of the Commodity? Collecting Boulle at Chatsworth

• Paul Giraud (Institut National du Patrimoine, France) — Collecting Italian 18th-Century Furniture at the Belle Epoque: The Origins of Interior Design

• Justine Lecuyer (Sorbonne, France) — Crafting Comfort: Upholstery and Textile Aesthetics in 19th-Century Interiors

• Eleonora Drago (Civic Museums of Treviso, Italy) — Paul Albert Bernard and the Decoration of the French Room at the Biennale in 1905: An Homage to Venice and France from a Decorative Skylight

Exhibition | The Count of Artois, Prince and Patron

Château de Maisons, in Maisons-Laffitte, a northwest outer suburb of Paris, about 12 miles from the city center

(Photo: © EPV / Thomas Garnier)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the Château de Versailles:

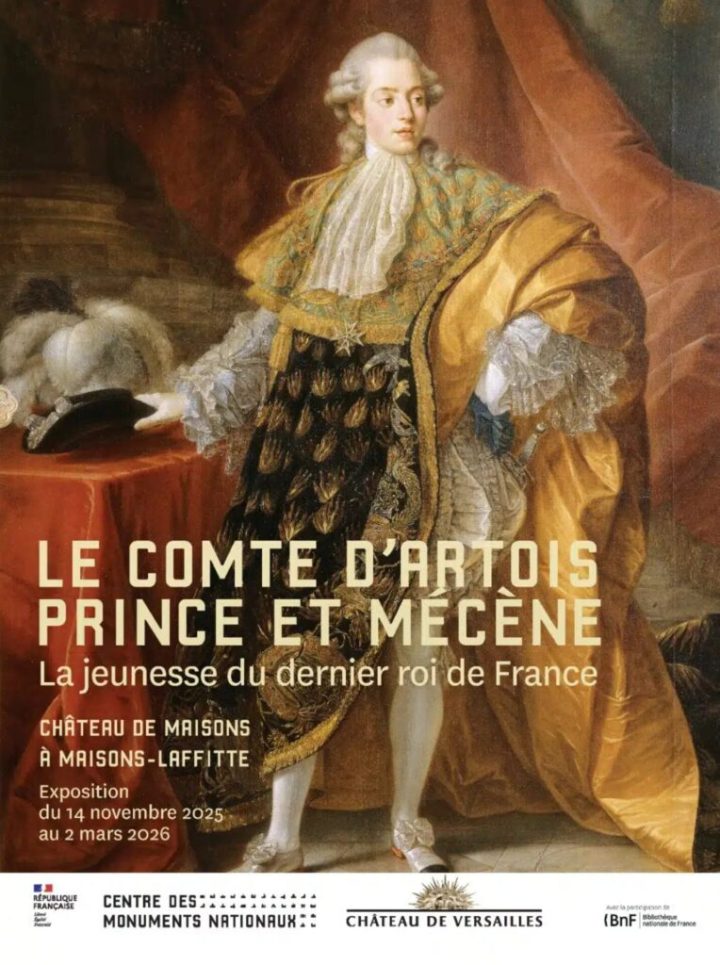

The Count of Artois, Prince and Patron: The Youth of the Last King of France

Château de Maisons, Maisons-Laffitte, 14 November 2025 — 2 March 2026

The result of a partnership between the Centre des Monuments Nationaux and the Palace of Versailles, this exhibition traces the life of the Count of Artois (1757–1836), brother of Louis XVI and the future Charles X, through his residences, his artistic projects, and his passions. From the splendor of the Château de Maisons to the count’s exile in 1789, it reveals the journey of a refined prince at the heart of the 18th century.

The exhibition begins with a presentation of the Château de Maisons in the 18th century and then traces the life of the Prince of Artois from his birth to his exile. The prince’s personality, his life, his patronage, and his taste are explored through a great variety of objects: graphic arts, paintings, objets d’art, sculptures, furniture, curiosities, and books. The exhibition also highlights the prince’s interest in architecture, as he was the last owner of the Château de Maisons under the Ancien Régime. Sourced primarily from the collections of the Palace of Versailles, the exhibition benefits from additional prestigious loans from the National Archives, the National Library of France, the Louvre Museum, the Mobilier National, the Château de Fontainebleau, the Carnavalet Museum, the Musée de l’Armée – Invalides, the municipal library of Versailles, and the Fine Arts Museums of Amiens and Reims, as well as from private collections.

The exhibition as installed at the Château de Maisons

(Photo: © EPV / Thomas Garnier)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The Count of Artois, Future Charles X

Reputed for his frivolous spirit and taste for luxury, the Count of Artois was both an attractive and controversial figure, eccentric yet conservative. Charles-Philippe of France, known under the title Count of Artois, was born in Versailles on 9 October 1757. He was the grandson of Louis XV and the brother of Louis XVI and the future Louis XVIII. He became King of France upon the death of the latter in 1824, under the name Charles X, and soon emerged as the representative of the most uncompromising Catholic faction. He was consecrated at Reims the following year. The July Ordinances of 1830, which restricted freedom of the press and dissolved the Chamber, triggered an uprising that became known as the Three Glorious Days. Faced with the revolt, Charles X abdicated and left France. His exile led him first to Scotland, then to Prague, and finally to Istria (a peninsula shared by Slovenia, Croatia, and Italy), where he died on 6 November 1836.

A Taste for Innovation

From an early age, the Count of Artois distinguished himself through his marked interest in splendor and refinement, coupled with an unrestrained passion for the modern currents of art and fashion. He was very close to Marie-Antoinette at the beginning of her reign, and they shared this common enthusiasm. However, unlike the queen, constrained by the demands of court etiquette, the Count of Artois enjoyed far greater freedom to adopt and promote the latest trends.

From an early age, the Count of Artois distinguished himself through his marked interest in splendor and refinement, coupled with an unrestrained passion for the modern currents of art and fashion. He was very close to Marie-Antoinette at the beginning of her reign, and they shared this common enthusiasm. However, unlike the queen, constrained by the demands of court etiquette, the Count of Artois enjoyed far greater freedom to adopt and promote the latest trends.

The château de Maisons, a masterpiece by François Mansart, was built from 1633 onward for René de Longueil, a magistrate of the Parliament of Paris. Designed as a pleasure residence, it became, as early as the 17th century, a place admired by the court. King Louis XIV himself visited it several times. In the following century, the estate entered a new era of splendor when, in 1777, the Count of Artois acquired it. He commissioned the architect François-Joseph Bélanger to transform the château with ambitious embellishment projects, refined interior decoration, and modern gardens. The count intended to make it both a setting for entertainment and a symbol of aristocratic refinement. But the upheavals of 1789 brought the work to a halt, and the prince’s property was confiscated.

After the Revolution, the château passed through various hands, from Marshal Lannes under the Empire to the banker Jacques Laffitte, who subdivided the park. The château was saved from ruin at the beginning of the 20th century thanks to its listing as a historic monument and its acquisition by the State. Today, restored and open to the public, the Château de Maisons remains a jewel of the Grand Siècle and still bears the mark of the Count of Artois’s lavish ambitions, whose tenure constitutes one of the most brilliant episodes in its history.

A Dialogue between Collections

The partnership established in 2013 between the Centre des Monuments Nationaux and the Palace of Versailles creates a dialogue between collections that are too often overlooked and major landmarks of France’s national heritage. Temporary exhibitions allow both institutions to pool their resources in order to offer as many people as possible the opportunity to discover, or rediscover, chapters of French history within the prestigious setting of national monuments. The CMN and the Palace of Versailles have concluded a deposit agreement that will allow the return and presentation, in situ, of works that were once at Maisons during the time of the Count of Artois, seized during the Revolution, and later kept at Versailles.

Curators

• Laurent Salomé, director of the National Museum of the Palaces of Versailles and Trianon

• Vincent Bastien, scientific collaborator at the Palace of Versailles

• Benoît Delcourte, chief curator at the Palace of Versailles

• Raphaël Masson, chief curator at the Palace of Versailles

• Clotilde Roy, responsible for enriching the collections of the Centre des Monuments Nationaux

• Gabriel Wick, doctor of history

Vincent Bastien, Benoît Delcourte, and Clotilde Roy, eds., Le Comte d’Artois, Prince et Mécène: La Jeunesse du Dernier Roi de France (Paris: Éditions du patrimoine, 2025), 96 pages, ISBN: 978-2757710821, €16.

At Christie’s | From the Collection of Arthur Georges Veil-Picard

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Happy Family (L’Heureuse Famille, alternatively: Young Couple Contemplating a Sleeping Child, The Return Home, or The Reconciliation), oil on canvas, 70 × 89 cm. Estimate: €1,500,000–2,000,000.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release (8 January) for the sale:

Chefs-d’oeuvre de la collection Veil-Picard, Auction #24451

Christie’s, Paris, 25 March 2026

On March 25, Christie’s is proud to present at auction a group of thirty masterpieces from the collection of Arthur Georges Veil-Picard (1854–1944). Rarely exhibited, this collection—whose works are often known only through black-and-white reproductions—remains among the most mysterious and coveted. Featuring works by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Hubert Robert, Jean-Antoine Watteau, Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, and Marie-Suzanne Roslin, the sale brings together the greatest names in 18th-century French painting and could, on its own, embody this golden age of art history in France. A true labor of love for the 18th century, the collection perfectly illustrates the joviality, sense of pleasure, and freedom so characteristic of the period. Estimated at €5–8 million, this exceptional ensemble represents a long-awaited event for collectors in search of masterpieces.

Marie-Suzanne Roslin, Madame Hubert Robert, née Anne-Gabrielle Soos, 1771, pastel. Estimate: €70,000–100,000.

Pierre Etienne, Vice President of Christie’s France and International Director of the Old Masters Department, and Hélène Rihal, Head of the Old Master and 19th-Century Drawings Department, note: “There are works one searches for over many years, desired even without having seen them. This is the case for these museum-quality pieces from the Veil-Picard collection, kept hidden within the family for decades. A heritage preserved with pride, which Christie’s is honored to unveil to the public for the first time. The sale is also an opportunity to pay tribute to Arthur Georges Veil-Picard, who assembled this unique collection purely out of his love for drawing and painting and his taste for marvelous images.”

Banker and brilliant entrepreneur at the helm of the renowned Pernod distillery, Arthur Georges Veil-Picard began building his collection in the early 20th century. A free-spirited collector—almost self-taught, instinctive, and passionate about the 18th century—he gathered important treasures in his private mansion in the Plaine Monceau district of Paris. Over forty years, he created an ensemble that remains a reference worldwide, especially among museum curators and collectors of Old Master paintings and drawings. A discerning connoisseur, Veil-Picard also inherited a lineage of knowledgeable collectors and generous benefactors of Alsatian origin. The Louvre and the Musée des Beaux-Arts et d’Archéologie in Besançon, the family’s hometown, benefited from this generosity on numerous occasions. Today, many works from the Veil-Picard collection are housed in the Louvre, Versailles, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Among Veil-Picard’s favorite artists, Fragonard best reflects the collector’s jovial character—he owned up to sixteen of his works, five of which are included in the sale. The centerpiece, The Happy Family, perfectly illustrates the ‘Fragonard style’ (€1,500,000–2,000,000). Painted in the 1770s, after the Italian journey that liberated the painter’s manner, this work showcases Fragonard’s lively, spontaneous brushwork. Its tender scene is enhanced by the voluptuousness of a deliberately playful composition. Of the various versions of the work, the one offered here is considered by scholars to be the first and most representative of Fragonard’s palette. Two other versions remain in private collections, and a preparatory study is held at the André Malraux Museum in Le Havre.

Hubert Robert, Madame Geoffrin’s Luncheon.

The same lightness is found in a delightful portrait, The Little Coquette, also known as The Peeping Girl (€400,000–600,000). This mischievous, tilted face offers the quintessence of Fragonard’s art: a painting of pleasure and spontaneity. Beyond its aesthetic and expressive qualities, it boasts a prestigious provenance, having belonged to Hippolyte Walferdin, a great admirer of 18th-century art, and later to Count de Pourtalès—collectors among the most enlightened of their time, still celebrated today. A charming, large wash drawing, Woman with a Dove, also came from Walferdin’s collection before being acquired by the Rothschild family (€200,000–300,000).

Intimate, confidential scenes remain highly prized by lovers of 18th-century painting. Works by Hubert Robert, Madame Geoffrin’s Luncheon and An Artist Presents a Portrait to Madame Geoffrin, perfectly exemplify this taste. Famous for her salon that gathered Enlightenment scholars and artists, Madame Geoffrin embodies the spirit of her century. These two paintings, depicting her in her drawing room and bedroom, brilliantly showcase Robert’s talent for capturing the atmosphere of his time. They are also the last works commissioned by this celebrated patron (estimate on request).

Among the twenty drawings in the collection, a large sheet in red chalk and black stone by Antoine Watteau stands out as a major rediscovery in the artist’s corpus. Illustrated in black and white in the 1996 catalogue raisonné of Watteau’s drawings, it was described there as “from an inaccessible private collection.” Reminiscent of the celebrated Pierrot in the Louvre, this Actor Holding a Guitar under His Arm has never been exhibited publicly (€600,000–800,000). A remarkable and joyful drawing by Gabriel de Saint-Aubin offers a vivid example of his talent as a chronicler of Parisian life. While female nudes were forbidden at the Academy, the artist depicts a painter and his model in the intimacy of the studio (The Private Academy, €150,000–200,000). A pastel by Marie-Suzanne Roslin, one of the rare female academicians of the Enlightenment, presents a delicate portrait of Madame Hubert Robert, née Anne-Gabrielle Soos (€70,000–100,000). Finally, in a more historical vein, the collection also includes two pairs of drawings dated 1783 by Jean-Michel Moreau, illustrating festivities held in honor of the Dauphin’s birth by the royal couple at the Hôtel de Ville (€300,000–500,000) and at the Palais Royal (€70,000–100,000).

Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, The Private Academy, 1776. Estimate: €150,000–200,000.

Exhibition | Virtue and Vice: Allegory in European Drawing

On view this spring at The Getty:

Virtue and Vice: Allegory in European Drawing

Getty Center, Los Angeles, 3 March — 7June 2026

This rotation from Getty’s collection explores how European artists from the 16th to 19th centuries made drawings to criticize bad behavior as well as praise virtuous deeds. Drawings of proper and improper conduct range from straightforward examples (charity, lust, and greed) to complex allegories (virtue, decadence, and friendship). Whether warning against sinful ways or celebrating how one should behave, drawings visualized moral codes, political ideologies, and social norms.

Image: Jacques de Gheyn II, Allegory of Avarice, ca. 1609, pen and brown ink, 18 × 13 cm (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2003.23).

Exhibition | Learning to Draw

Hubert Robert, A Draftsman in the Capitoline Gallery, detail, ca. 1765, red chalk, 46 × 34 cm

(Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 2007.12)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Now on view at The Getty:

Learning to Draw

The Getty Center, Los Angeles, 21 October 2025 — 25 January 2026

Drawing is a skill, gained like any other through study and practice. Combining the movement of the hand with the dedication of the mind, drawing was considered the foundation of the arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture since the Renaissance. Proficiency in drawing was critical for exploring, inventing, and communicating ideas visually, but how was this foundational ability actually learned? This exhibition explores artistic training and the mastery of drawing in Europe from about 1550 to 1850.

Call for Papers | The Lessons of Rome

From ArtHist.net:

Les Leçons de Rome / The Lessons of Rome, 9th Edition

Lyon Museum of Fine Arts, 13 March 2026

Proposals due by 15 February 2026

This study day aims to provide a space of reflection for anyone who grasps Italy as an architectural, urban, and landscape research laboratory. Defining Italy as a laboratory involves analyzing contexts of urban policies as well as design experiences, theories, practices, legacies, mutations, and prospects. It means building knowledge and culture, learning and developing tools to conceive the present and to enrich contemporary practices. The Lessons of Rome will provide an opportunity to engage current and upcoming research, to share existing and generate new knowledge and dialogues with Italy. Professionals, students, PhD candidates, researchers, and people from various academic disciplines, schools, and nationalities are welcome. Th study day is organized in partnership by the Ecole nationale supérieur d’architecture de Lyon, the LAURE, the Institut Culturel Italien of Lyon, and the Lyon Museum of Fine Arts.

Researchers wishing to contribute are invited to send a proposal with a title, an abstract (about 200 words), and a short biography to rome@lyon.archi.fr before 15 February 2026. The official language of the day is French, but proposals and papers may also be submitted in English.

Scientific Committee

Nicolas Capillon, Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Lyon

Julie Cattant, Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Lyon

Benjamin Chavardès, Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Lyon

Lorenzo Ciccarelli, Università degli studi di Firenze

Philippe Dufieux, Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Lyon

Federico Ferrari, Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Paris-Malaquais

Audrey Jeanroy, Université de Tours

Manuel Lopez Segura, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University

Alessandro Panzeri, Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture de Lyon

Davide Spina, The University of Hong Kong

Call for Papers | Rethinking Early Modern Prints, 15th–18th Centuries

From ArtHist.net:

Rethinking Early Modern Prints Today: New Questions and New Approaches

Actualités et perspectives de la recherche sur l’estampe à l’époque moderne

Université de Poitiers, CRIHAM, 24 September 2026

Proposals due by 16 February 2026

This symposium aims to bring together established researchers, early career scholars, PhD candidates, and students—in art history or related disciplines—to present and discuss current research and perspectives on prints in the early modern period (15th–18th centuries). It seeks to provide a forum for exchange devoted to recent approaches and ongoing projects, whether they focus on the practices and techniques of printmaking, on its networks of production, circulation, and exchange, or on the place of the printed image within visual and material culture. Presentations, lasting around twenty minutes, may address, without geographical restriction, any aspect of the production, circulation, or reception of prints, from historical, artistic, material or theoretical perspectives.

As part of the Creation, Corpus, Heritage (Création, corpus, patrimoine) program of the Centre de Recherches Interdisciplinaires en Histoire, Histoire de l’Art et Musicologie (CRIHAM), the symposium will take place at the University of Poitiers and will also be available via videoconference. Please submit an abstract with a title (in French or English) of no more than 2500 characters (including spaces) and a short biographical note (institutional affiliation, contact details, and research topics) by 16 February 2026 to je.rechercheestampe@gmail.com.

Organizers

• Teoman Akgönül, University of Poitiers (CRIHAM) and INHA

• Amélie Folliot, Rennes 2 University (HCA)

• Estelle Leutrat, University of Poitiers (CRIHAM)

• Louise Quentel, University of Poitiers (CRIHAM)

leave a comment