Journal18 | Pendant Essays on Paint Boxes

Left: Partial view of the contents of Charlotte Martner’s paint box (Private collection; author’s photograph). Right: Caspar Schneider, Paint box on stand, ca. 1789, mahogany on oak structure, 75 cm high (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Recent pieces from J18′s Notes & Queries:

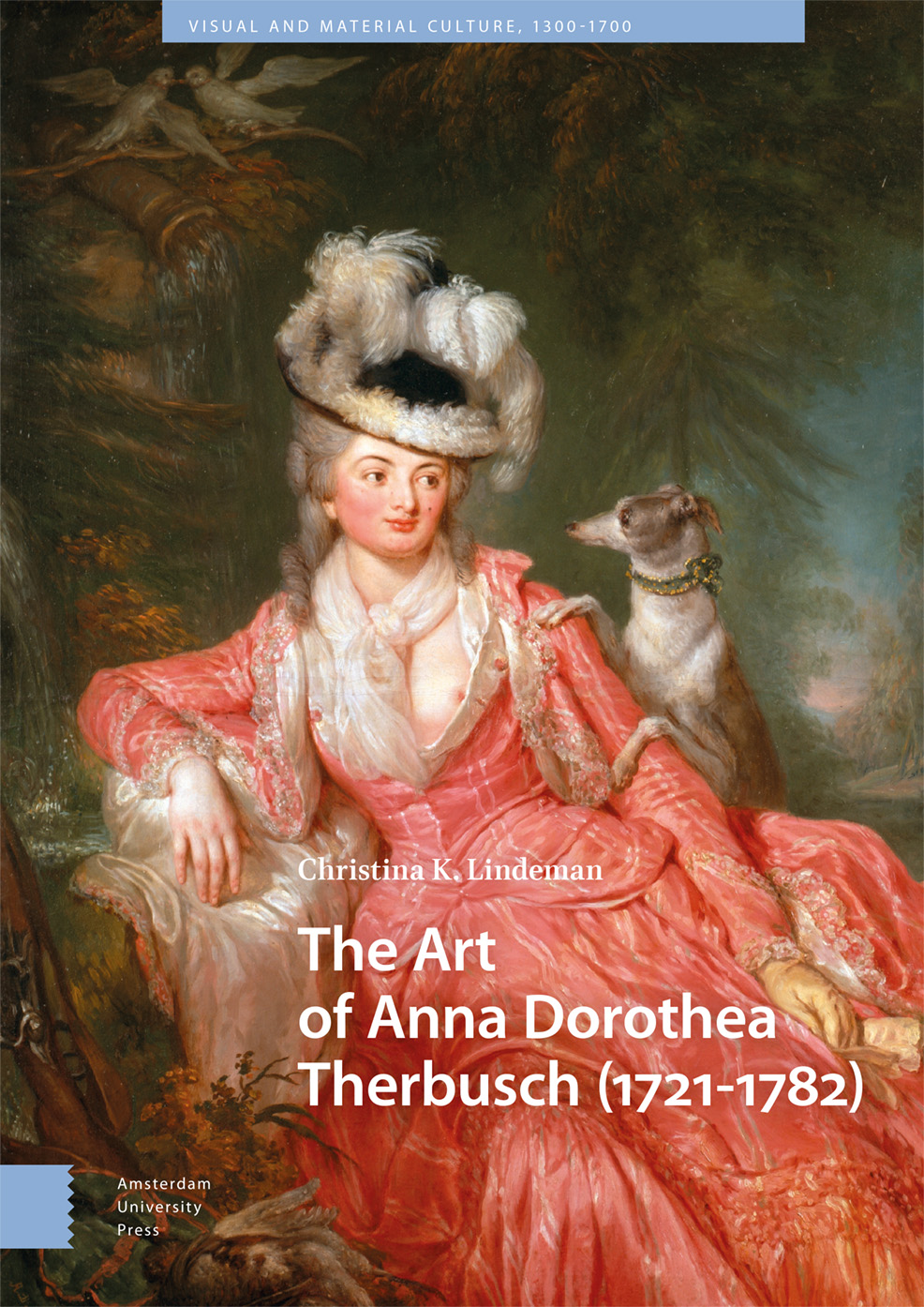

Conceived as pendants, these two essays by David Pullins and Damiët Schneeweisz unpack two paint boxes that belonged to Marie Victoire Lemoine (1754–1820) and Charlotte Daniel Martner (1781–1839), bringing out how these boxes tie the material history of painting to gender, colonialism, and enslavement.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

David Pullins, “Contained Assertions: Marie Victoire Lemoine’s Paint Box,” Journal18 (December 2023).

Marie Victoire Lemoine, The Interior of a Woman Painter’s Atelier, 1789, oil on canvas, 116.5 × 88.9 cm (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Holding a loaded palette, brushes and maulstick, a standing woman represents the art of painting, while a second woman seated on a low stool embodies the foundational art of drawing (Fig. 1).[1] Their practices converge in the canvas underway on an easel, depicting a priestess presenting a young woman to a statue of Athena, goddess-protectress of the arts, in which chalk outlines have begun to be fleshed out in color. But the allegory has been dressed in contemporary terms, pointedly situating Marie Victoire Lemoine’s The Interior of a Woman Painter’s Atelier in the year it was executed, 1789, and boldly taking on the language of genre painting that was used more often to critique than to promote women artists. Michel Garnier’s A Young Woman Painter from the same year offers a counter-image (Fig. 2). A painter sets her canvases aside (literally turned to the wall, her easel reflected distantly in the mirror), while she is distracted by love (signaled by the dove, flowers, and book propped on an insubstantial table easel). In contrast to Lemoine’s somber, antique mise-en-abyme, Garnier chooses an unfinished “Greuze girl” as his gloss. . . .

The full essay is available here»

David Pullins is Associate Curator in the Department of European Paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Damiët Schneeweisz, “Laboring Likeness: Charlotte Daniel Martner’s Paint Box in Martinique (1803–1821),” Journal18 (December 2023).

Charlotte Martner, Self-Portrait with Four People, 1805, watercolor on ivory and cardboard, 14.5 × 11.5 cm (Private collection).

In Charlotte Daniel Martner’s self-portrait miniature (1805), the classical tendencies of French eighteenth-century portraiture collide with a distinctive burgeoning Antillean visual culture of the early nineteenth century (Fig. 1).[1] The miniature is a contrast in colors: the artist’s luminous pale white skin and Empire dress, emanating from the portrait’s ivory ground like moonlight, set against the darker skin tones of the man, women, and child that surround her, each dressed in dulled shades of red, orange, blue, and beige. The precise status of the four Black individuals within this household is unclear, and they are yet to be identified, but their placement, each suspended in an act of domestic labor, suggests that perhaps they depict those then enslaved in Martner’s home. At the center of the portrait is a brisk loss, as if someone has pressed their thumb to the watercolor and swept away Martner’s features, leaving only a set of auburn eyes, the contours of a nose, dark-brown eyebrows, and loose curls pinned back with a bejeweled comb. . .

The full essay is available here»

Damiët Schneeweisz is a PhD Candidate at The Courtauld Institute of Art currently on Doctoral Placement at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

Journal18, Fall 2023 — Cold

The latest issue of J18:

Journal18, Issue #16 (Fall 2023) — Cold

Issue edited by Michael Yonan

Feeling cold is increasingly a privilege in our warming world. Regions of the world known for temperate, moderate climates are becoming accustomed to erratic weather. Cooler areas of the globe are warming, and warmer areas becoming too hot to occupy. Accompanying these climatological transformations are humanity’s attempts to control temperature, led by the invention of technologies (most prominently air conditioning) which help us live comfortably, but which come with substantial human, economic, and environmental costs. By creating pleasant temperatures in which to live and work, we exacerbate the problem that makes human intervention into the climate more urgent.

Feeling cold is increasingly a privilege in our warming world. Regions of the world known for temperate, moderate climates are becoming accustomed to erratic weather. Cooler areas of the globe are warming, and warmer areas becoming too hot to occupy. Accompanying these climatological transformations are humanity’s attempts to control temperature, led by the invention of technologies (most prominently air conditioning) which help us live comfortably, but which come with substantial human, economic, and environmental costs. By creating pleasant temperatures in which to live and work, we exacerbate the problem that makes human intervention into the climate more urgent.

The cause of these changes is the consumption of fossil fuels, which transformed human life profoundly in the pursuit of modernity. The origin of this transformation falls squarely within the long eighteenth century. The established scientific terminus post quem for measuring human effects on global temperatures is the year 1800. Moreover, the 1700s were the final century of the Little Ice Age, a climatological phenomenon characterized by lower global mean temperatures. With these conditions in mind, might temperature play a greater role in our discussion of eighteenth-century art? For this issue of Journal18, I have invited scholars to address this possibility. My goal is to encourage reflection on how eighteenth-century art might engage the scholarly literatures on historical climatology and the history of the senses. Do the conditions of eighteenth-century life, as filtered through artistic production, help us understand why the world became warmer? Can we find in the eighteenth century’s ideas about temperature the roots of our current beliefs, and perhaps locate in art ways of rethinking or undoing the assumptions that have brought us to this place?

The essays offered here address these concerns from multiple perspectives, engage varied works of art, and do so in diverse regions of the globe. Jennifer Van Horn examines an eighteenth-century plate warmer, made circa 1790, owned by George Washington and used in his residences, to reveal its place within a racially determined temperature-scape. She achieves this by analyzing not only how it mediated temperatures for its socially prominent owners, but also how it reveals the experiences of the enslaved individuals who tended it during dinners. She thereby locates the warmer’s effect on bodies, its thermoception, within the “complex entanglements of cold, race, unfreedom, and materiality” of early America to produce a “racialized thermal order.”

Sylvia Houghteling’s essay takes us to a different region of the globe, South Asia, and to a different problem, namely creating cool temperatures for inhabitants of a hot climate. Houghteling shows that South Asian societies produced sophisticated systems of cooling long before colonial occupation, but these early techniques often relied on creating the psychological effect of cold by stimulating other senses, notably smell and sight. She thereby produces a synesthetic framework for temperature modification, one in which the senses interconnect. This approach offers insight into how to produce art history that is sensually engaged, not just in an erotic dimension, but in the ability to imagine complex sensual entanglements through the past’s material remains.

Alper Metin leads us to the Ottoman Empire, where he investigates the history of a warming device appreciated across the world: the fireplace. Eighteenth-century Ottoman patrons adapted fireplace designs from Western models, and in so doing responded to substantial socioeconomic and cultural changes in Ottoman society. These included the desire for increased comfort in domestic interiors and the need to display wealth and sophistication through a fireplace’s decoration. Metin reflects on the Ottoman Turkish terminology for fireplaces, revealing both gendered and socio-ethnic dimensions to its language, and on morphological changes to fireplace design. Fireplaces emerge as more than just warming devices, but rather as creations that express changing conditions and mentalities in a society rethinking its international place.

Our shorter notices take up these themes in further directions. Kaitlin Grimes shows how the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway incorporated narwhal ivory into conceptions of royal power that both supported and materialized its colonial project in the Arctic Atlantic. Etienne Wismer demonstrates that melting glaciers in Switzerland (much in the news today) fascinated Europeans in the years around 1800, spurring scientific investigations, inspiring interior decoration, and generating new health regimens. Both Grimes and Wismer explore the relationship between what Wismer calls a “biotope” and the human beings who inhabited it. I would add that art mediates the relationship between humanity and biotope, and that temperature is a central force constituting their interconnection.

Issue Editor

Michael Yonan, University of California, Davis

a r t i c l e s

• Jennifer Van Horn — Racialized Thermoception: An Eighteenth-Century Plate Warmer

• Sylvia Houghteling — Beyond Ice: Cooling through Cloth, Scent, and Hue in Eighteenth-Century South Asia

• Alper Metin — Domesticating and Displaying Fire: The Technical and Aesthetic Evolution of Ottoman Fireplaces

s h o r t e r p i e c e s

• Kaitlin Grimes — Narwhal Ivory as the Arctic Colonial Speciality of the Kingdom of Denmark-Norway

• Etienne Wismer — Making Sense of Ice? Engaging Meltwater in the Long Eighteenth Century in Switzerland and France

All articles are available here»

Call for Articles | Spring 2025 Issue of J18: Africa, Beyond Borders

From the Call for Papers:

Journal18, Issue #19 (Spring 2025) — Africa: Beyond Borders

Issue edited by Prita Meier, Hermann von Hesse, and Finbarr Barry Flood

Proposals due by 1 April 2024; finished articles will be due by 1 September 2024

Since the dawn of decolonization in 1950s and 1960s Africa, Africanist scholars have emphasized Africa’s connections to the rest of the world before the period of European colonialism. While such views have gained widespread currency among Africanists and some Africanist-adjacent scholars and journals, Africa, apart from the continent’s Mediterranean coast, is hardly discussed beyond these circles. Even when medieval and early modern (art)history and material culture studies claim to be global, Africa often remains on the periphery of the discussion of long-distance trade, artistic innovations, and material cultural exchange.

This special issue of Journal18 invites contributions that examine the confluence of the global, interregional, and local in shaping African arts, material culture, and sartorial practices. It seeks to shift standard accounts of globalization by decentering European empire-building and the colonial archive. The long eighteenth century saw the expansion of African polities and local networks of exchange flourished. Internal trade and migration were just as important as oceanic movements. Traders, merchants, and migrants constantly moved between different societies, actively facilitating the intermingling of diverse cultural forms across great distances. Artisans, both free and enslaved, were also highly mobile during this period. Archipelagic Africa, especially its port cities and mercantile polities, played a significant role in shaping the commodity networks of the entire world.

Among the questions that this issue seeks to address are: Can the discussions of African trade objects help us historicize intra-and inter-continental trade and cultural exchanges? How did African royals, travelers, enslaved, and free individuals engage with the foreign and the faraway? What can African artifacts tell us about religious, aesthetic, and cultural transformations in Africa and its internal or transregional diasporas before the colonial period? What can historic African art collecting tell us about African identities and transcultural negotiations? How did Africa inspire global artistic imaginations during this dynamic period?

We welcome proposals for contributions on related topics, including African architectural forms and notions of space; the visualization of race in pre-colonial Africa; cultures of making and their regional and transregional connections; the reception and reimagining associated with transregional or transcultural reception; African writing and graphic systems; the material cultures of enslaved/free Africans and their experiences of migration and diaspora; and the politics of eighteenth-century heritage conservation.

To submit a proposal, send an abstract (250 words) and brief biography to the following addresses: editor@journal18.org and spm9@nyu.edu, vonhesse@illinois.edu, fbf1@nyu.edu. Articles should not exceed 6000 words (including footnotes) and will be due by 1 September 2024. For further details on submission and Journal18 house style, see Information for Authors.

Issue Editors

Prita Meier, New York University

Hermann von Hesse, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign

Finbarr Barry Flood, New York University

leave a comment