Exhibition | Celebrity in Print

From the press release (9 September 2024) for the upcoming exhibition:

Celebrity in Print

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, 9 November 2024 — 8 November 2025

Curated by Katie McKinney

Edward Fisher, after Mason Chamberlin, Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, London, 1763, mezzotint (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1968-154).

Before the 18th century, consumers in the Atlantic world lacked wide access to images of famous people other than monarchs. Broad circulation of engraved portraiture changed all that, and, for the first time, people could put a recognizable likeness or caricature with a name they might have heard or read about in a newspaper. Starting in November, visitors to the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, one of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, will learn how a market was developed for images of newsworthy or notable writers, actors, criminals, social climbers, athletes, politicians, and military figures. Celebrity in Print—on view in the Michael L. and Carolyn C. McNamara Gallery from 9 November 2024 until 8 November 2025—will showcase approximately 30 objects illustrating the impact celebrities had on material culture. From recognizable people in colonial government to ordinary people who led extraordinary lives, portrait prints featured in the exhibition will be paired with examples of porcelain, silver, and archeological fragments.

“Like their modern counterparts, 18th-century celebrities were trendsetters,” said Ron Hurst, the Foundation’s chief mission officer. “People on both sides of the Atlantic admired the clothing, furnishings, and houses of the famous. Those who could afford to do so sought to emulate those fashions, sometimes even referencing the possessions of a particular luminary. Celebrity in Print will allow our visitors to get a glimpse of those bygone leading lights.”

Among the more recognizable examples of colonial government notables to be featured in Celebrity in Print is Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). Long before he became a Revolutionary statesman who helped draft the Declaration of Independence and acted as the first Ambassador to France, Franklin was already well known as a printer, writer, scientist, and inventor. In Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, a mezzotint made in London in 1763 after a work by Mason Chamberlin, several of Franklin’s most famous experiments are depicted including the lightening rod. After the print was published in England, his son ordered 200 copies to sell in Philadelphia. Franklin enjoyed handing the print out to his friends and correspondents, especially those he could not visit in person, as this was apparently a favorite likeness of his.

George Washington (1732–1799), perhaps the most well-known figure in the Colonies during the Revolutionary War, was also a person of great interest abroad. English print publishers were quick to capitalize on the public’s interest in news from the war in America. Although George Washington, Esqr., a mezzotint made in London in 1775, is inscribed “Drawn from life by Alex.r Campbell of Williamsburgh in Virginia,” the artist’s name is fictitious; the real artist’s identity is unknown. Washington wrote to Colonel Joseph Reed to thank him for sending him a copy of the print, noting in January 1776 that, “Mr. Campbell whom I never saw to my knowledge, has made a very formidable figure of the Commander-in-Chief, giving him a sufficient portion of terror in his countenance.” The fact that the portrait bore little resemblance to Washington was not important to a public eager to get a look at the American general.

Celebrity in Print also explores how print media offered an opportunity for writers, artists, and actors to become famous not only for their work but for who they themselves were. Plays, prints, and stories of famous actors crossed the Atlantic leading to demand for portraits and descriptions of their authors or actors who made roles famous.

“Just as today we use ever-expanding technologies to shape and share our image, artists, actors, politicians, athletes, and socialites of the past used the printed word and images to expand their influence and fame,” said Katie McKinney, Colonial Williamsburg’s Margaret Beck Pritchard curator of maps and prints. “The word ‘celebrity’ wasn’t used in the modern sense until the 19th century, but the phenomenon certainly can trace its origins to 18th-century print culture.”

James MacArdell after Francis Hayman, Mr. Woodwarde in Character of ye Fine Gentleman in Lethe, 1740–65, mezzotint (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1973-318).

One way in which an author’s literary intellect was portrayed to his audience was through the use of an engraved portrait, or frontispiece, at the beginning of a publication. An exhibition highlight is the image of Charles Ignatius Sancho (ca. 1729–1780) from his posthumous book Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho, an African (London, 1782)—a copy of which was purchased by Joseph Prentis (1754–1809) of Williamsburg (Prentis was an enslaver). Sancho was apparently born to enslaved parents who died shortly after his birth. At age two, his enslaver gave him as a ‘gift’ to three sisters in Greenwich, England, where he was poorly treated. John, Duke of Montagu, noticed his interest in education and encouraged him to learn. After the Duke’s death, Sancho ran away to join the Montagu household where he rose to the rank of butler. As a high-ranking servant for an important family, Sancho met and corresponded with many of the leading literary figures of his day. After leaving domestic service, he became a grocer in Westminster, where he raised a family with his wife. As a property-owning man, he was able to vote, making him the first Black man in England known to vote in a parliamentary election. An abolitionist, Sancho frequently wrote about the intelligence and potential of people of African descent at a time when racist ideas reinforced slavery by casting Black people as inferior. As letter writing in the 18th century was considered an art form, and it was often expected in elite circles that letters would be read aloud and shared, Sancho developed a reputation for his skillful, entertaining, and powerful letters. While Sancho’s genius was largely unknown outside of a small group of England’s cultural, literary, and political elite until after his death in 1780, it changed when his friends gathered his letters and published an edited version of them to benefit his widow and children.

Figure of Henry Woodward, Bow Porcelain Manufactory, London, 1750–53, soft-paste porcelain (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1968-228).

Just as today, actors were known not only for the roles they played but also as public figures in their own right. Audiences were interested in their personal lives and backgrounds as well as their performances. These actors were often depicted in prints wearing costumes or striking poses that represented their most famous roles. Portraits of actors, poets, and creative figures served as inspiration for ceramic figures, and their appearance appeared on handkerchiefs, snuffboxes, and drinking vessels. One example featured in Celebrity in Print is of the successful British actor Henry Woodward (1714–1777) who was known for his comedic performances. The soft-paste porcelain figure of Woodward, made by the Bow Porcelain Manufactory in London (1750–53), is based on a print that showed him as ‘The Fine Gentleman’, one of his most celebrated characters from David Garrick’s first play, Lethe, or Esop in Shades, first performed in London on 15 April 1740. Woodward’s character, dressed in an absurd outfit, poked fun at wealthy Englishmen who traveled through Europe on what was known as the Grand Tour. Upon their return, it was feared that they would adopt foreign dress, customs, and tastes. The play, which was popular in the Colonies, was performed in New York, Philadelphia, Annapolis, and Charleston.

Models and fashionable society women are celebrated today, and the same was true in the 18th century. At mid-century, Elizabeth Gunning was one of the most portraited women in Britain. A likeness of her in mezzotint, Elizabeth, Dutchess of Hamilton and Argyll, made in London in 1770 after work by Catherine Read, is also featured in the exhibition. Born in Ireland to a family of minor nobility, Elizabeth and her sister Maria (another noted beauty) became instant celebrities when they were presented to London society in 1751. The Duke of Hamilton was so taken with 17-year-old Elizabeth that they married that same evening, sealing the nuptials with a bed curtain ring. After his death several years later, she married John Campbell, who became the 5th Duke of Argyll. She and her sister both suffered for their beauty, however, due to the dangerous white lead contained in the cosmetics they wore. Elizabeth recovered, but her sister died from lead poisoning at the age of 27.

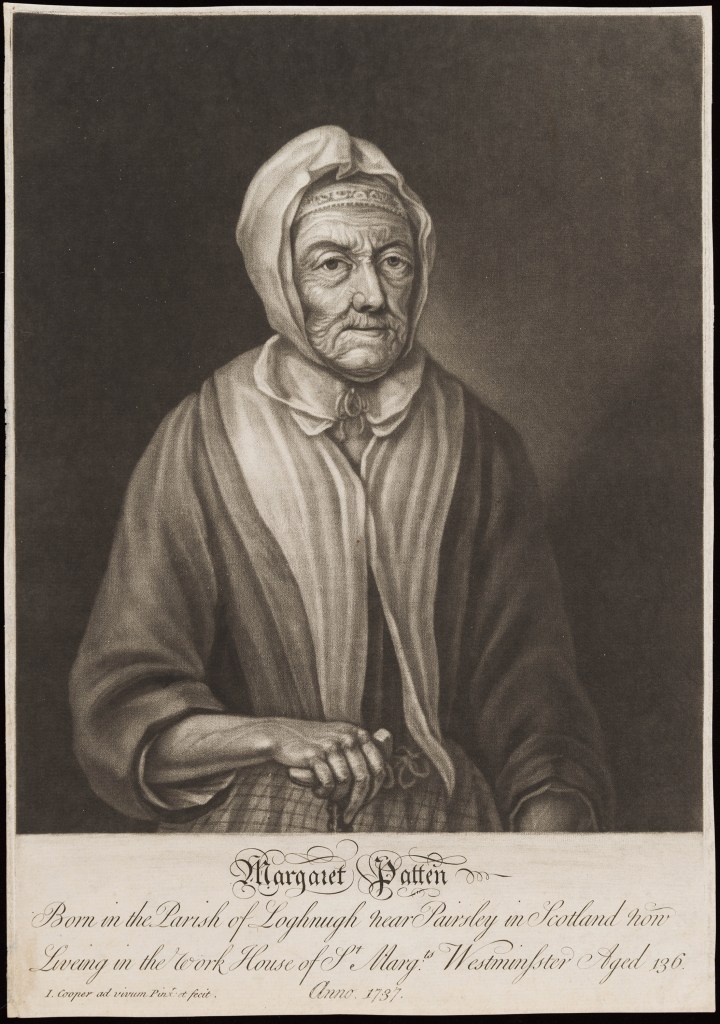

After John Cooper, Portrait of Margaret Patten, 1737, mezzotint engraving on laid paper (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1979-312).

Printed likenesses also helped create celebrity among ordinary people who led extraordinary lives. One such woman was Margaret Patten (b.? –1739). Given that 50 was considered the threshold of old age, it is not surprising that Patten, who claimed to be 136 years old in 1737, attracted attention. News of her long life reached newspapers throughout the English Colonies, and people were especially interested in Patten’s secret to long life. Descriptions mention that she was “very hearty,” took long walks, and drank only milk. At the end of her life, Patten lived in a workhouse in London where she died in 1739. The mezzotint included in the exhibition is based on a portrait by John Cooper painted at the request of local officials to hang in the workhouse to commemorate Patten’s long life.

William Ansah Sessarakoo (c. 1736–1770) was the son of John Corrantee, a prominent Fante man from the port city of Annamaboe, Ghana, and a powerful cultural intermediary between African merchants on the interior and European slave traders on the coast. To strengthen his position with Europeans, Corrantee sent one son to be educated in France, and his other, William, to study in England in 1744. En route, Sessarakoo boarded a slave ship on its way to Barbados. When the captain died, no one remained on board to verify his identity or legal status, and he remained in Barbados where he was enslaved. For several years, his father petitioned European officials to investigate his son’s whereabouts. Finally, a ship was sent to Barbados to find him, and after four years enslaved, Sessarakoo sailed to England. The public was fascinated with his story and hailed him as “the prince of Annamaboe.” His wrongful enslavement and visit to London inspired ballads, plays, memoirs, and art, including a 1749 mezzotint engraved by John Faber Jr.

leave a comment