Exhibition | Figures of the Fool

Opening next month at the Louvre:

Figures of the Fool: From the Middle Ages to the Romantics

Musée du Louvre, Paris, 16 October 2024 — 3 February 2025

Curated by Élisabeth Antoine-König and Pierre-Yves Le Pogam

Fools are everywhere. But are the fools of today the same as the fools of yesteryear? This fall, the Musée du Louvre is dedicating an unprecedented exhibition to the myriad figures of the fool, which permeated the pictorial landscape of the 13th to the 16th centuries. Over the course of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the fool came to occupy every available artistic space, insinuating himself into illuminated manuscripts, printed books and engravings, tapestries, paintings, sculptures, and all manner of objects both precious and mundane. His fascinating, perplexing and subversive figure loomed large in the turmoil of an era not so different from our own.

Fools are everywhere. But are the fools of today the same as the fools of yesteryear? This fall, the Musée du Louvre is dedicating an unprecedented exhibition to the myriad figures of the fool, which permeated the pictorial landscape of the 13th to the 16th centuries. Over the course of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the fool came to occupy every available artistic space, insinuating himself into illuminated manuscripts, printed books and engravings, tapestries, paintings, sculptures, and all manner of objects both precious and mundane. His fascinating, perplexing and subversive figure loomed large in the turmoil of an era not so different from our own.

The exhibition examines the omnipresence of fools in Western art and culture at the end of the Middle Ages, and attempts to parse the meaning of these figures, who would seem to play a key role in the advent of modernity. The fool may make us laugh, with his abundance of frivolous antics, but he also harbours a wealth of hidden facets of an erotic, scatological, tragic or violent nature. Capable of the best and of the worst, the fool entertains, warns or denounces; he turns societal values on their head and may even overthrow the established order.

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, Yard with Madmen, 1794 (Dallas: Meadows Museum).

Within the newly renovated Hall Napoléon, this exhibition, which brings together over 300 works from 90 French, European and American institutions, brings us on a one-of-a-kind journey through Northern European art (English, Flemish, Germanic, and above all French), illuminating the profane aspects of the Middle Ages and revealing a fascinating era of surprising complexity. The exhibition explores the disappearance of the figure of the fool with the Enlightenment and the triumph of reason, and its resurgence at the end of the 18th century and all throughout the 19th. The fool then became a figure with which artists identified, wondering: ‘What if I were the fool?’

The exhibition is curated by Élisabeth Antoine-König, Senior Curator in the Department of Decorative Arts, and Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, Senior Curator in the Department of Sculptures, Musée du Louvre.

With the support of the Cercle des Mécènes du Louvre, the Fondation Etrillard and the New York Medieval Society.

Élisabeth Antoine-König and Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, eds., Figures du Fou: Du Moyen Âge aux Romantiques (Paris: Musée du Louvre éditions / Gallimard, 2024), 448 pages, ISBN: 978-2073073037, €45.

Exhibition | An Actor with No Lines — Pierrot

Watteau, Pierrot, also known as Gilles, detail, ca. 1718–19, oil on canvas, 1.84 × 1.56 meters

(Paris: Musée du Louvre).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

This exhibition opens in October at The Louvre in conjunction with the The Fool . . .

A New Look at Watteau: An Actor with No Lines — Pierrot, Known as Gilles

Musée du Louvre, Paris, 16 October 2024 — 3 February 2025

Curated by Guillaume Faroult

Watteau’s Pierrot, formerly known as Gilles, is one of the most famous masterpieces in the Louvre’s collection. This enigmatic work, which has long raised questions for art historians, is currently undergoing conservation treatment at the Centre for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France, after which time it will be the focus of a spotlight exhibition.

Louis Crépy after Antoine Watteau, Self-Portrait (Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France).

Nothing is known about the painting before it was discovered by the artist and collector Dominique Vivant Denon (1747–1825), Director of the Louvre under Napoleon. It soon came to be regarded as a Watteau masterpiece and garnered praise from renowned writers and art historians. It has often been seen as reflecting a certain image of the 18th century—mischievous, cynical, or melancholy, depending on the author and the era. Its fame boosted the return to favour of 18th-century art in the age of Manet and Nadar.

The exhibition will present the findings of the conservation project, approaching this wholly original work—whose attribution to Watteau has sometimes been questioned—both as part of the artist’s oeuvre and in the cultural and artistic context of the time. Alongside many other paintings and drawings by Watteau, there will be works by his contemporaries: painters, draughtsmen, engravers (Claude Gillot, Antoine Joseph Pater, Nicolas Lancret, Jean Baptiste Oudry, Jean Honoré Fragonard, etc.), and writers (Pierre de Marivaux, Alain-René Lesage, JeanFrançois Regnard, Evaristo Gherardi), with special emphasis on the rich theatrical repertoire of the time.

As soon as the painting entered the Louvre in 1869, via the bequest of Louis La Caze (1798–1869), it became a favourite with generations of viewers. Its powerful appeal is partly due to its outstanding quality, but also to its originality for the period and to the mystery surrounding its production.

The exhibition will also explore the painting’s rich and varied critical reception and its far-reaching artistic legacy. This powerful, enigmatic image has greatly inspired French writers, including Théophile Gautier, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, George Sand, the Goncourt brothers, and Jacques Prévert. The painting has also influenced photographers, filmmakers, and musicians (Nadar, Marcel Carné, Arnold Schoenberg), as well as visual artists (Edouard Manet, Gustave Courbet, Pablo Picasso, André Derain, Juan Gris, James Ensor, Georges Rouault, and Jean-Michel Alberola), driving them to new creative heights.

The show will explore the fascinating conversations between these great creative minds and Watteau’s enigmatic painting, even as it resonates harmoniously with the Figures of the Fool exhibition scheduled for the same dates in the Hall Napoléon.

Guillaume Faroult, Revoir Watteau: Un comédien sans réplique. Pierrot, dit le Gilles (Musée du Louvre Éditions and Liénart Éditions, 2024), 240 pages, €40.

Exhibition | Mary Robinson: Actress, Mistress, Writer, Radical

Now on view at Chawton House, as noted at Art History News:

Mary Robinson: Actress, Mistress, Writer, Radical

Chawton House, Hampshire, 2 September 2024 — 21 April 2025

Attributed to John Hoppner, Portrait of Mrs. Robinson as Perdita, 1782, oil on canvas, 79 × 66 cm (Chawton House, Hampshire).

“Her name is Robinson, … she is I believe almost the greatest and most perfect beauty of her sex.”

—Prince of Wales to Mary Hamilton, December 1779

“She is a woman of undoubted Genius … I never knew a human Being with so full a mind—bad, good, & indifferent, I grant you, but full, & overflowing.”

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Robert Southey, 25 January 1800

The first exhibition dedicated to the scandalous life and literary genius of Mary Robinson.

A star of the London stage, Mary Robinson (1757–1800) became notorious as a royal mistress. From treading the boards of London’s theatres, to gracing the gossip columns of newspapers, Robinson pioneered celebrity status. She lit up the fashion world, sparking trends with her choice of outfit or carriage, and she went on to light up the literary world with novels, poems, and essays. A talented poet, she developed her distinctive poetic style alongside some of the best-known writers of the day, and she honed her political ideas in the radical circle around William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Long remembered only for her relationship with the Prince of Wales (later George IV)—who fell in love with her on stage as Perdita in The Winter’s Tale—Mary Robinson has in recent decades been reclaimed as one of the most important and overlooked writers of the late 18th century. This exhibition traces the extraordinary journey of her life and artistic development from the most famous woman in England to social outcast, exploring her hard-won second career as one of the most popular and influential writers of her day. Rare and early editions of her writing—from the debut novel that sold out by lunchtime on the day it was published to her impassioned argument for women’s rights—are brought together with scant surviving manuscript material from collections and archives across the UK. These will be interpreted alongside the portraits, engravings, and caricatures through which her image was circulated and her reputation both shaped and ruined. Her compelling biography enables reflections on the complexity of female celebrity and sexuality, at the time and in society today.

Chawton House is a Grade II-listed Jacobean manor house in the village of Chawton, adjacent to Alton, Hampshire that once belonged to Jane Austen’s brother, Edward. Chawton House is now a centre for early women’s writing with a collection of over 4,500 rare books and manuscripts written by women from 1660 to 1860. Since 2015 it has been open to the public as an historic house, telling the story of the Austen and Knight families and pioneering women writers.

Exhibition | Celebrity in Print

From the press release (9 September 2024) for the upcoming exhibition:

Celebrity in Print

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, 9 November 2024 — 8 November 2025

Curated by Katie McKinney

Edward Fisher, after Mason Chamberlin, Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, London, 1763, mezzotint (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1968-154).

Before the 18th century, consumers in the Atlantic world lacked wide access to images of famous people other than monarchs. Broad circulation of engraved portraiture changed all that, and, for the first time, people could put a recognizable likeness or caricature with a name they might have heard or read about in a newspaper. Starting in November, visitors to the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, one of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, will learn how a market was developed for images of newsworthy or notable writers, actors, criminals, social climbers, athletes, politicians, and military figures. Celebrity in Print—on view in the Michael L. and Carolyn C. McNamara Gallery from 9 November 2024 until 8 November 2025—will showcase approximately 30 objects illustrating the impact celebrities had on material culture. From recognizable people in colonial government to ordinary people who led extraordinary lives, portrait prints featured in the exhibition will be paired with examples of porcelain, silver, and archeological fragments.

“Like their modern counterparts, 18th-century celebrities were trendsetters,” said Ron Hurst, the Foundation’s chief mission officer. “People on both sides of the Atlantic admired the clothing, furnishings, and houses of the famous. Those who could afford to do so sought to emulate those fashions, sometimes even referencing the possessions of a particular luminary. Celebrity in Print will allow our visitors to get a glimpse of those bygone leading lights.”

Among the more recognizable examples of colonial government notables to be featured in Celebrity in Print is Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790). Long before he became a Revolutionary statesman who helped draft the Declaration of Independence and acted as the first Ambassador to France, Franklin was already well known as a printer, writer, scientist, and inventor. In Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia, a mezzotint made in London in 1763 after a work by Mason Chamberlin, several of Franklin’s most famous experiments are depicted including the lightening rod. After the print was published in England, his son ordered 200 copies to sell in Philadelphia. Franklin enjoyed handing the print out to his friends and correspondents, especially those he could not visit in person, as this was apparently a favorite likeness of his.

George Washington (1732–1799), perhaps the most well-known figure in the Colonies during the Revolutionary War, was also a person of great interest abroad. English print publishers were quick to capitalize on the public’s interest in news from the war in America. Although George Washington, Esqr., a mezzotint made in London in 1775, is inscribed “Drawn from life by Alex.r Campbell of Williamsburgh in Virginia,” the artist’s name is fictitious; the real artist’s identity is unknown. Washington wrote to Colonel Joseph Reed to thank him for sending him a copy of the print, noting in January 1776 that, “Mr. Campbell whom I never saw to my knowledge, has made a very formidable figure of the Commander-in-Chief, giving him a sufficient portion of terror in his countenance.” The fact that the portrait bore little resemblance to Washington was not important to a public eager to get a look at the American general.

Celebrity in Print also explores how print media offered an opportunity for writers, artists, and actors to become famous not only for their work but for who they themselves were. Plays, prints, and stories of famous actors crossed the Atlantic leading to demand for portraits and descriptions of their authors or actors who made roles famous.

“Just as today we use ever-expanding technologies to shape and share our image, artists, actors, politicians, athletes, and socialites of the past used the printed word and images to expand their influence and fame,” said Katie McKinney, Colonial Williamsburg’s Margaret Beck Pritchard curator of maps and prints. “The word ‘celebrity’ wasn’t used in the modern sense until the 19th century, but the phenomenon certainly can trace its origins to 18th-century print culture.”

James MacArdell after Francis Hayman, Mr. Woodwarde in Character of ye Fine Gentleman in Lethe, 1740–65, mezzotint (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1973-318).

One way in which an author’s literary intellect was portrayed to his audience was through the use of an engraved portrait, or frontispiece, at the beginning of a publication. An exhibition highlight is the image of Charles Ignatius Sancho (ca. 1729–1780) from his posthumous book Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho, an African (London, 1782)—a copy of which was purchased by Joseph Prentis (1754–1809) of Williamsburg (Prentis was an enslaver). Sancho was apparently born to enslaved parents who died shortly after his birth. At age two, his enslaver gave him as a ‘gift’ to three sisters in Greenwich, England, where he was poorly treated. John, Duke of Montagu, noticed his interest in education and encouraged him to learn. After the Duke’s death, Sancho ran away to join the Montagu household where he rose to the rank of butler. As a high-ranking servant for an important family, Sancho met and corresponded with many of the leading literary figures of his day. After leaving domestic service, he became a grocer in Westminster, where he raised a family with his wife. As a property-owning man, he was able to vote, making him the first Black man in England known to vote in a parliamentary election. An abolitionist, Sancho frequently wrote about the intelligence and potential of people of African descent at a time when racist ideas reinforced slavery by casting Black people as inferior. As letter writing in the 18th century was considered an art form, and it was often expected in elite circles that letters would be read aloud and shared, Sancho developed a reputation for his skillful, entertaining, and powerful letters. While Sancho’s genius was largely unknown outside of a small group of England’s cultural, literary, and political elite until after his death in 1780, it changed when his friends gathered his letters and published an edited version of them to benefit his widow and children.

Figure of Henry Woodward, Bow Porcelain Manufactory, London, 1750–53, soft-paste porcelain (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1968-228).

Just as today, actors were known not only for the roles they played but also as public figures in their own right. Audiences were interested in their personal lives and backgrounds as well as their performances. These actors were often depicted in prints wearing costumes or striking poses that represented their most famous roles. Portraits of actors, poets, and creative figures served as inspiration for ceramic figures, and their appearance appeared on handkerchiefs, snuffboxes, and drinking vessels. One example featured in Celebrity in Print is of the successful British actor Henry Woodward (1714–1777) who was known for his comedic performances. The soft-paste porcelain figure of Woodward, made by the Bow Porcelain Manufactory in London (1750–53), is based on a print that showed him as ‘The Fine Gentleman’, one of his most celebrated characters from David Garrick’s first play, Lethe, or Esop in Shades, first performed in London on 15 April 1740. Woodward’s character, dressed in an absurd outfit, poked fun at wealthy Englishmen who traveled through Europe on what was known as the Grand Tour. Upon their return, it was feared that they would adopt foreign dress, customs, and tastes. The play, which was popular in the Colonies, was performed in New York, Philadelphia, Annapolis, and Charleston.

Models and fashionable society women are celebrated today, and the same was true in the 18th century. At mid-century, Elizabeth Gunning was one of the most portraited women in Britain. A likeness of her in mezzotint, Elizabeth, Dutchess of Hamilton and Argyll, made in London in 1770 after work by Catherine Read, is also featured in the exhibition. Born in Ireland to a family of minor nobility, Elizabeth and her sister Maria (another noted beauty) became instant celebrities when they were presented to London society in 1751. The Duke of Hamilton was so taken with 17-year-old Elizabeth that they married that same evening, sealing the nuptials with a bed curtain ring. After his death several years later, she married John Campbell, who became the 5th Duke of Argyll. She and her sister both suffered for their beauty, however, due to the dangerous white lead contained in the cosmetics they wore. Elizabeth recovered, but her sister died from lead poisoning at the age of 27.

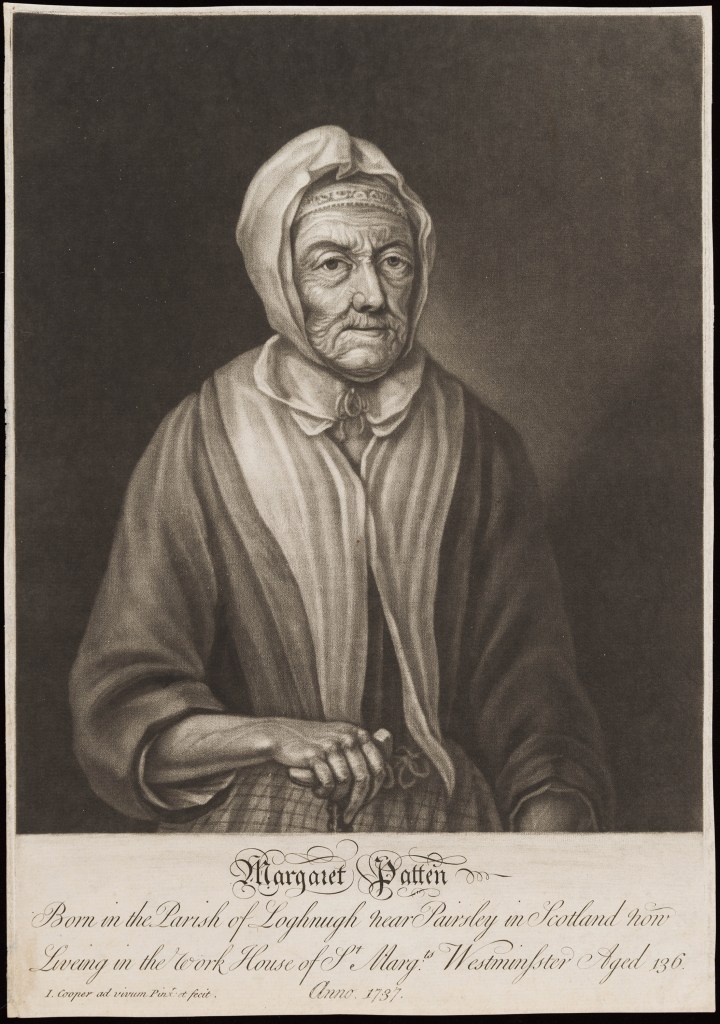

After John Cooper, Portrait of Margaret Patten, 1737, mezzotint engraving on laid paper (Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, Museum Purchase, 1979-312).

Printed likenesses also helped create celebrity among ordinary people who led extraordinary lives. One such woman was Margaret Patten (b.? –1739). Given that 50 was considered the threshold of old age, it is not surprising that Patten, who claimed to be 136 years old in 1737, attracted attention. News of her long life reached newspapers throughout the English Colonies, and people were especially interested in Patten’s secret to long life. Descriptions mention that she was “very hearty,” took long walks, and drank only milk. At the end of her life, Patten lived in a workhouse in London where she died in 1739. The mezzotint included in the exhibition is based on a portrait by John Cooper painted at the request of local officials to hang in the workhouse to commemorate Patten’s long life.

William Ansah Sessarakoo (c. 1736–1770) was the son of John Corrantee, a prominent Fante man from the port city of Annamaboe, Ghana, and a powerful cultural intermediary between African merchants on the interior and European slave traders on the coast. To strengthen his position with Europeans, Corrantee sent one son to be educated in France, and his other, William, to study in England in 1744. En route, Sessarakoo boarded a slave ship on its way to Barbados. When the captain died, no one remained on board to verify his identity or legal status, and he remained in Barbados where he was enslaved. For several years, his father petitioned European officials to investigate his son’s whereabouts. Finally, a ship was sent to Barbados to find him, and after four years enslaved, Sessarakoo sailed to England. The public was fascinated with his story and hailed him as “the prince of Annamaboe.” His wrongful enslavement and visit to London inspired ballads, plays, memoirs, and art, including a 1749 mezzotint engraved by John Faber Jr.

Call for Papers | Scottish Society for Art History: Art and Text

From ArtHist.net:

Scottish Society for Art History: Art and Text

National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, 6–7 February 2025

Proposals due by 25 October 2024

The Scottish Society for Art History (SSAH), in partnership with the National Library of Scotland, will host a two-day in-person event exploring the relationship between art and the written word in Scotland.

Scottish art has long been inspired by literature, while Scottish artists and publishers have made fundamental contributions in the fields of book and magazine illustration, advertising posters, comics, graphic novels, and artists’ books. In turn, there has been a significant body of writings on Scottish art in both fiction and non-fiction, and many outstanding collaborations between artists and writers. This conference will share current research and critical debate into the myriad relationships between art and text and we hope to engage with artists, writers, curators, archivists, art historians, literary and linguistic scholars, and interdisciplinary researchers. Topics include, but are not limited to:

• Art inspired by literature

• Critical writing on art

• Fiction and poetry inspired by art

• Artists’ books

• Concrete poetry

• Posters and advertising

• Banners and protest art

• Illuminated manuscripts

• Comics, magazines, and book illustration

• The relationship between art and text in theatre, performance art, video, and multimedia art

• Collaborations between artists and writers

• Artists’ archives

• Crossovers between art history, literary history, and Scottish studies

• Art and art history relating to Scots, Gaelic, and Doric

We welcome proposals for 20-minute papers or 10-minute case studies to be presented in person at the event. Proposals should be in the form of 300- to 500-word abstracts, accompanied by brief biographical details and a supporting image. The deadline for proposals is 5pm on Friday, 25 October 2024. If you would like to discuss the CFP in greater detail or submit an abstract, please contact Matthew Jarron at m.h.jarron@dundee.ac.uk.

The organisers are unable to provide speakers’ fees, but all speakers will receive free entry to the event, promotion via social media as part of the event, and publication opportunities. A selection of papers from the conference will be published in the Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History.

Exhibition | André Charles Boulle

Closing soon at the Musée Condé:

André Charles Boulle

Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly, 8 June — 6 October 2024

Curated by Mathieu Deldicque, with Sébastien Evain and William Iselin

Writing Table of the Prince of Condé, long-term lease from the Château de Versailles to the Condé Museum (RMN-Grand Palais / A. Didierjean)

The collection of the Condé Museum in Chantilly features two desks by one of the greatest French cabinetmakers of all time, André Charles Boulle. From June to October 2024, the Grands Appartements of the Princes of Condé at the Château de Chantilly will host the first-ever exhibition in France to explore Boulle’s life and work.

The show brings together this ingenious designer’s most significant pieces, commissioned by the most illustrious patrons in France—the King, the Grand Dauphin, the Prince of Condé, and the Duchess of Burgundy—in a celebration of French furniture-making excellence, its techniques, and unrivalled grace. The life and long career of André Charles Boulle (1642–1732) need little introduction. Cabinetmaker, artist, and artisan, Boulle worked for the Bâtiments du roi, the department of the King’s Household responsible for building works, for more than half a century, and he and his workshop produced pieces for the Royal Family and the French nobility. He achieved high technical perfection, particularly in metal-and-tortoiseshell marquetry, which he raised to new heights. An ingenious bronzesmith, Boulle established the use of gilt-bronze in furniture and gave his creations a unique look. He was also a curious collector and a talented draughtsman who took pains to bring his production to a broader audience, notably through engravings. Synonymous with the sumptuousness of French art under Louis XIV, he achieved recognition in his lifetime, and his name has been celebrated ever since.

André Charles Boulle was a leading figure in the development of French furniture in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Besides the commode, one of his most influential designs at the end of Louis XIV’s reign was the flat-topped writing table (bureau plat). Besides producing desks on six legs and desks with several drawers on each side supported by eight legs, Boulle invented a new type of desk, with a single row of three drawers in the frieze, resting on four legs. This flat writing table made his reputation, and brass-and-tortoiseshell marquetry, rich gilt-bronze mounts, and slender, curved shapes became the hallmark of elegance in furniture and the ultimate symbol of power. They were produced in increasingly large numbers from the second decade of the eighteenth century until the early years of the Régence. The innovations made by Boulle defined the shape of the French writing table for more than half a century.

The exhibition charts developments in desk design, shape, and decoration through a large and varied display of desks by Boulle, each with a long-established provenance. Furniture with ‘part’ and ‘counterpart’ marquetry is presented side by side in a way that reveals their beauty and helps visitors learn more about them. Key pieces produced by the same workshop will complete this fascinating survey and put this unparalleled production into its broader context. Bookcases, consoles, stands, torchères, caskets, chandeliers, medal cabinets, and bookbindings—all of illustrious provenance—remind us of this ingenious artist’s versatile talent and creativity.

The exhibition is curated by Mathieu Deldicque, Lead Heritage Conservator, Director of the Conde museum, in collaboration with Sébastien Evain, conservator and independent expert, a specialist in French 18th-century furniture and objets d’art, and William Iselin, an expert in French 18th-century furniture and objets d’art. In partnership with the Château de Versailles, the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Mathieu Deldicque, ed., André Charles Boulle (Saint-Rémy-en-l’Eau: Éditions d’art Monelle Hayot, 2024), 304 pages, ISBN: 979-1096561452, €39.

Lecture | Adrienne Childs on Pearls and Blackamoors

Presented by the Lewis Walpole Library and the Wadsworth Atheneum:

Adrienne Childs | Pearl Drops and Blackamoors: The Black Body and Pearlescent Adornment in European Art

Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, 10 October 2024, 6pm

Nicolaes Berchem, A Moor Offering a Parrot to a Lady (detail), ca. 1660–70, oil on canvas (Hartford: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 1961.29).

European artists of the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries often depicted Black figures wearing pearl ornaments. The contrast evoked notions of luxury, distant lands, and exoticism. Art historian and curator Adrienne L. Childs, PhD explores the complexities of subjugating and enslaving Black bodies in one context and using their images to showcase luxuries in another. Before the lecture, meet at 5pm in the galleries to view works from the museum’s European art collection. Free and open to the public with registration encouraged.

The lecture is offered in connection with the exhibition The Paradox of Pearls: Accessorizing Identities in the Eighteenth Century, curated by Laura Engel, Professor, Duquesne University, on view at the Lewis Walpole Library until 31 January 2025.

Adrienne L. Childs is an independent scholar, art historian, and curator. She is Senior Consulting Curator at The Phillips Collection in Washington, DC. Her current book project is an exploration of Black figures in European decorative arts entitled Ornamental Blackness: The Black Figure in European Decorative Arts, forthcoming from Yale University Press (2025). She is co-curator of Vivian Browne: My Kind of Protest for The Phillips Collection (on view until September 2025). She recently co-curated The Colour of Anxiety: Race, Sexuality and Disorder in Victorian Sculpture at The Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, England. She was the guest curator of Riffs and Relations: African American Artists and the European Modernist Tradition at The Phillips Collection in 2020. Childs was awarded the 2022 Driskell Prize from The High Museum of Art in recognition of her contribution to African American art and art history. She holds a BA from Georgetown University, an MBA from Howard University, and a PhD in the History of Art from the University of Maryland. Currently, Childs serves as the Distinguished Scholar at the Leonard A. Lauder Center at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Colloquium | American Art, Empire, and Material Histories

This fall at Historic Deerfield:

Reawakening Materials: American Art, Empire, and Material Histories in Historic Deerfield’s Collection

Historic Deerfield, Deerfield, Massachusetts, 7–8 November 2024

Historic Deerfield announces Reawakening Materials: American Art, Empire, and Material Histories in Historic Deerfield’s Collection, a public colloquium focused on the institutions’ collection of paintings, works on paper, and decorative arts from Thursday, 7 November to Friday, 8 November 2024. Questions of ’empire’ emerged from an interest in scholars rethinking the American experience from the lens of global European empires (England, Spain, France, The Netherlands, etc.) and U.S. imperialism. Historic Deerfield’s collection focuses on 18th-and 19th-century American art and material culture, and it is based in a landscape tied to Indigenous communities, histories of enslaved people and free people of African descent, and settler colonialism.

The colloquium will explore relationships between empire, materials of objects, and settler colonialism in the collection, specifically asking how these art historical topics can be generative for recontextualizing Historic Deerfield’s place in the study of New England history, art, and culture. Speakers will investigate materials that reveal new ideas of empire, including: pastels, lacquer, birch, engravings on paper, and linen. The program will also workshop methods for telling these narratives through historic interiors, including objects tied to violence and absence, and opportunities to bring in stories of joy and survivance.

Keynote speaker

• Charmaine Nelson, Provost Professor, Black Diasporic Art & Visual Culture, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Additional speakers

• Megan Baker, PhD Candidate in Art History, University of Delaware and 2024–25 Smithsonian Institution Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery

• Mary Amanda McNeil, Assistant Professor, Department of Studies in Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora, Tufts University

• Lan Morgan, Associate Curator, Peabody Essex Museum

• Joseph Litts, PhD Candidate in Art History, Princeton University

• Jonathan Square, Assistant Professor of Black Visual Culture, Parsons School of Design

• Morgan Freeman, PhD Candidate in American Studies, Yale University

• Michael Hartman, Jonathan Little Cohen Associate Curator of American Art and PhD Candidate in Art History, University of Delaware

• Anthony Trujillo, PhD Candidate in American Studies, Harvard University

Online registration will be posted shortly. Please send questions to Ian Hamilton, ihamilton@historic-deerfield.org.

Symposium | Guillaume Lethière

Next week at The Clark, in connection with the exhibition:

Guillaume Lethière Symposium

The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, 27 September 2024

Join us for a symposium in celebration of Guillaume Lethière. The exhibition, organized in partnership with the Musée du Louvre, is the first to investigate Lethière’s extraordinary career. This one-day conference invites renowned scholars and the public to examine Lethière’s considerable body of work, as well as the presence and reception of Caribbean artists in France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Join us for a symposium in celebration of Guillaume Lethière. The exhibition, organized in partnership with the Musée du Louvre, is the first to investigate Lethière’s extraordinary career. This one-day conference invites renowned scholars and the public to examine Lethière’s considerable body of work, as well as the presence and reception of Caribbean artists in France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

More information is available here»

s c h e d u l e

10.00 Director’s Welcome — Olivier Meslay, Hardymon Director, Clark Art Institute

10.05 Opening Remarks — Esther Bell, Deputy Director and Robert and Martha Berman Lipp Chief Curator, Clark Art Institute

10.25 Session One

• Guillaume Lethière: The Exceptional Trajectory of a Free Person of Color — Frédéric Régent, Maître de Conférences and Directeur de Recherche, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

• Lethière’s Allegorical Confines: Indemnity, Colonialism, and African Diasporic Fantasies — C. C. McKee, Assistant Professor of the History of Art and Director of the Center for Visual Culture, Bryn Mawr College

12.05 Break and Exhibition Viewing

1.05 Session Two

• Colonial Networks: Remapping the ‘Paris’ Art World in the French Antilles — Meredith Martin, Professor of Art History, New York University and the Institute of Fine Arts

• Picturesque Plantations: Jenny Prinssay’s Construction of a French Caribbean Idyll — Remi Poindexter, The Graduate Center, CUNY, and University Fellow in Art History at the University of North Carolina Asheville

2.45 Break

3.50 Session Three

• Guillaume Lethière’s Roman Years — Francesca Alberti, Director of the Department of Art History at the Académie de France in Rome–Villa Medici and Professor of Art History at the Université de Tours and the Centre d’Études Supérieures de la Renaissance

• From Neoclassicism to Preromanticism: Lethière, the Missing Link? — Richard-Viktor Sainsily-Cayol, Multimedia Visual Artist and Urban Scenographer

4:50 Closing Remarks — Esther Bell

5.00 Reception

Call for Papers | Le vrai, le faux: Festival de l’histoire de l’art

From ArtHist.net:

Le vrai, le faux: Festival de l’histoire de l’art / The True, the False: Festival of Art History

Fontainebleau, 6–8 June 2025

Proposals due by 3 November 2024

En 2024, la région autrichienne du Salzkammergut porte le titre de Capitale européenne de la culture. Si nous le mentionnons, c’est d’une part pour montrer qu’au-delà de Vienne, Linz ou Salzbourg, l’Autriche recèle des lieux culturels qui en font le pays invité de cette 14e édition du festival de l’histoire de l’art mais c’est aussi parce que cette région abrite le village d’Hallstatt. Ce charmant bourg de près de 800 âmes est inscrit sur la liste du patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO, un classement qui ne l’a pas empêché d’être reconstruit à l’identique (lac inclus !) dans la province de Guangdong dans le sud-ouest de la Chine. Parler simplement d’Hallstatt a-t-il encore un sens ? Ne vaut-il mieux pas préciser « Hallstatt en Autriche » et « Hallstatt en Chine » ? Ou bien faut-il dire « Hallstatt l’originale » ? Y a-t-il alors une « vraie Hallstatt » et une « fausse Hallstatt » ? Le village construit en Chine n’est-il pas aussi réel que celui construit en Autriche ? Et si l’on répond à cette question par la négative, quels arguments convoquer ? L’origine géographique ? L’antériorité temporelle ? L’authenticité ?

En novembre 2017 a eu lieu, au palais de justice de Paris, dans les salons de la Cour de cassation, un colloque réunissant trois cent cinquante magistrats, juristes, conservateurs, historiens de l’art et experts. Au cœur de leurs discussions, l’évolution nécessaire de la loi du 9 février 1895 dite « loi Bardoux », seule loi dans l’arsenal juridique français à réprimer les « fraudes en matière artistique »[1] et établissant une distinction entre le faux et la contrefaçon[2].

Que faire de ces objets pris dans le champ du vrai et du faux ? Les exposer ? Les cacher dans les réserves ? Que faire des restaurations des édifices advenues au fil des siècles ? Faut-il montrer les strates historiques d’un édifice ou bien s’en tenir à la dernière version en date ? Autant d’interrogations qui touchent au cœur même de l’histoire de l’art et de ses métiers. Interroger le vrai et le faux dans l’histoire de l’art, ses discours et ses pratiques, exige de prendre en compte les glissements qui peuvent s’opérer entre ces deux notions et au sujet desquelles la réflexion se forme et se transforme au fil du temps et de bien garder à l’esprit que les partages entre vrai et faux se font selon des critères très différents en fonction des contextes culturels et historiques.

Rien n’a été plus normal, tout au long de l’histoire de l’art et ce, jusqu’à une époque relativement récente, que la répétition des formes et des œuvres sans altération de la valeur des premières créées. Bien que certains sculpteurs grecs ou romains, certains orfèvres ou architectes médiévaux aient l’habitude de signer leurs œuvres, la notion d’originalité de la création artistique comme fondement de la valeur d’une œuvre n’existait pas au sens où nous l’entendons aujourd’hui. Les premières anecdotes artistiques posant le problème du vrai et du faux en art occidental datent de la Renaissance. Le cupidon de Michel-Ange offert comme un antique au cardinal de San Giorgio, la copie sur cuivre par Marc-Antoine Raimondi des gravures sur bois d’Albrecht Dürer et l’utilisation par le premier du monogramme du second sont des topoï de la littérature artistique. La culture européenne de la première modernité n’ignorait pas le lien entre valeur artistique et authenticité de l’œuvre mais il ne s’agissait pas de penser les œuvres comme vraies ou fausses. Du XVIe au XIXe siècle, les copies, les pastiches, les interprétations sur d’autres médiums étaient nombreuses et leur utilité — pédagogique, politique, mémorielle — et leur valeur résidaient plus dans leurs qualités techniques que dans leur degré d’authenticité.

Le XIXe siècle marque un tournant dans l’importance conférée à cette notion. En 1885, le petit-fils de Jacques-Louis David publiait un texte intitulé Quelques observations sur les 19 toiles attribuées à Louis David à l’exposition des portraits du siècle (1783–1883). Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts (V. Havard, Paris, 1883). Sur ces dix-neuf toiles, il en reconnaît quatre, en accepte six autres et en exclue huit[3]. Jacques-Louis-Jules David fait donc œuvre d’expert et son jugement vaut pour homologation de l’œuvre de son aïeul. La figure de l’expert, qu’il ou elle soit artiste, historien de l’art ou critique, prend ainsi une importance nouvelle, capable de réduire à peau de chagrin le catalogue d’un artiste comme de le faire grossir plus que de mesure. À partir de la seconde moitié du XXe siècle, le faux et son créateur, le faussaire, deviennent les antagonistes majeurs des historiens de l’art, des experts, des musées et institutions culturelles. Ce n’est qu’avec ce qu’on appelle la « post-modernité » que le double, la copie et parfois le faux redeviennent des opérations artistiques et esthétiques à part entière[4]. Mais le faux peut aussi, pour certains artistes, être un objet politique. Lorsque le collectif d’artistes et d’auteurs italiens Wu Ming tentait de faire advenir dans les journaux d’informations nationaux ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui des fake news, ce n’était pas dans le but de tromper mais bien de faire comprendre les mécanismes de la tromperie en rendant ensuite le stratagème public[5]. À l’ère de la post-vérité, nous pourrons poser la question de la réussite et des risques d’une telle utilisation du vrai et du faux. Aujourd’hui, les images générées par l’intelligence artificielle, elle-même nourrie d’images existantes, sortent du paradigme de la copie ou de la citation et obligent à repenser les notions d’auctorialté et d’authenticité[6].

Le thème choisi pour cette 14e édition du festival de l’histoire de l’art embrasse tous les champs de notre discipline, c’est pourquoi il est utile de dégager quelques pistes de travail qui ne sont, bien sûr, pas exhaustives :

• Entre « vrai » et « faux » : « Vrai » et « faux » sont les deux pôles d’une réflexion qui porte en premier lieu sur l’unique et le multiple. Les propositions pourront s’attacher ainsi au statut des différents types de production artistique qui viennent redoubler l’œuvre originale : il en va ainsi de l’interprétation (retranscription de l’originale dans une technique différente), du pastiche (travail réalisé à partir d’une œuvre par un autre artiste pour souligner la manière du premier), de la copie (reproduction fidèle d’une œuvre qui s’annonce comme telle) et bien évidemment du faux, dont les modalités varient entre la contrefaçon intentionnelle (la copie que l’artiste ou le vendeur n’annonce PAS comme telle mais comme original), la falsification de l’authenticité ou encore la reproduction non autorisée d’œuvres protégées par des droits d’auteur.

• Des histoires de « faux » : L’histoire de l’art est remplie d’œuvres et d’objets qui ont été à un moment considéré comme authentiques et dont on a par la suite démontré qu’il s’agissait de « faux », soit exécutés volontairement pour tromper, soit mal identifiés par celles et ceux qui les ont acquis, exposés et commentés. Les propositions pourront porter sur telle ou telle « affaire » plus ou moins célèbre, sur la manière dont le caractère faux ou inauthentique des œuvres ou d’un ou plusieurs éléments de celles-ci a été découverte, sur les modifications des discours qui ont pu en surgir. La parole des restauratrices et restaurateurs sera ici particulièrement précieuse.

• Techniques et reproductibilité technique: les questionnements autour du vrai et du faux, de l’unique et du multiple, doivent tenir compte des conditions de production. L’une des problématiques principales de cette édition est l’œuvre d’art aux époques de sa reproductibilité technique, de l’estampe à la photographie aux images numériques actuelles. Ces techniques reproductives successives soulèvent la problématique de l’œuvre originale et de ce que Walter Benjamin appelle son « aura », un concept qui se trouve aujourd’hui détaché des œuvres originales précisément à cause des techniques modernes de reproduction[7]. La dimension technique, celle qui permet à un artiste qui copie ou à un faussaire qui falsifie de s’approcher au plus près du style d’un artiste doit nous retenir et nous amener à nous demander où commence le faux. La création du faux requiert un véritable art de la contrefaçon et si un faussaire repenti souhaite venir partager ses secrets techniques avec le public du festival, qu’il ou elle s’en sente bienvenu.

• Plaisir de tromper et d’être trompé: dans l’Antiquité puis à partir de la Renaissance, le concept de mimesis possède une importance capitale dans les théories de l’art. Pourra ainsi être interrogée la notion de trompe l’œil qui, quel que soit le medium utilisé, cherche à donner par une exacte représentation l’illusion de la présence de l’objet figuré. Les grandes figures — réelles ou légendaires — de ce genre (Zeuxis et Parrhasios, Bramante, Le Bernin, Cornelis Gijsbrechts ou Louis-Léopold Boilly) pourront être convoquées mais il faudra également convier à nos débats les philosophes qui ont interrogé ce genre et qui et qui contestent la parfaite adéquation du trompe l’œil à la réalité et parlent plutôt du plaisir donné par une illusion connue [8].

• Restauration et authenticité : la notion de restauration ou de restitution authentique ou « à l’identique » varie fortement suivant les contextes historiques et culturels.

• L’histoire de l’art face au faux: quelle(s) position(s) pour l’historien/historienne de l’art face à cette question du vrai et du faux ? Dans une optique historiographique, nous invitons les participantes et participants à se pencher sur la fascination mais aussi la difficulté que certains grands noms de notre discipline ont éprouvé face à ces sujets. Toute aussi importante est la réflexion sur l’appréciation relative qui est attachée à la valeur d’authenticité. Ce qui est considéré comme non-authentique dans une culture, ne l’est pas forcément dans l’autre. Nous sommes particulièrement intéressés à élargir les exemples au-delà de l’art européen. Et puis, il serait intéressant de voir comment l’histoire de l’art peut s’emparer, si ce n’est du faux tout du moins de la fiction, sur un plan méthodologique. Certains de nos collègues historiens et historiennes travaillent depuis plusieurs années selon la méthode de l’histoire contrefactuelle[9]. Et si ? Et s’il existait une histoire de l’art contrefactuelle ? La méthode contrefactuelle, voici un futur encore trop peu advenu dans le champ de l’histoire de l’art qu’il serait pertinent d’interroger.

• De l’utilité du faux: aujourd’hui, la valeur de la copie ou de la reproduction ne se conçoit plus en fonction de la virtuosité qu’elles affichent mais de leur utilité. Les fac-similés permettent de montrer des œuvres et des lieux majeurs de l’histoire de l’art trop fragiles pour être visibles, voire de replacer dans son contexte original une œuvre déplacée. Cette problématique engage de nombreuses questions techniques, notamment celle de l’échelle de ces fac-similés (l’échelle 1 des moulages du musée des monuments français et les dimensions inférieures de la « réplique » de la grotte Cosquer à Marseille ne peuvent être mis sur le même plan), des matériaux utilisés pour les produire (voir le travail par exemple de l’atelier Factum Arte à Madrid dont l’imprimante assure des impressions reproduisant la couleur et le relief) et de la dimension éthique de leur utilisation (objectif uniquement financier, accessibilité du public et protection de l’œuvre, défi technique).

• Connoisseurship versus analyses scientifiques: traditionnellement, les arguments d’authenticité étaient fondés sur les analyses stylistiques qui permettaient d’attribuer une œuvre à un artiste. Aujourd’hui, et ce déjà depuis quelques décennies les méthodes et les outils scientifiques, parfois de laboratoires travaillant de concert avec les institutions culturelles (le C2RMF du Louvre ou le Labart à Louvain-la-Neuve), opposent au discours des experts celui des sciences dites dures. Si parfois les deux discours peuvent en effet s’affronter, comme pour les termes « vrai » et « faux », une opposition aussi binaire et manichéenne n’a pas lieu d’être. Le festival sera heureux de faire dialoguer ces deux méthodes tant « l’intervention du laboratoire dans les questions de critique d’art [est] l’une des principales révolutions [contemporaines][10]. »

• Le droit et la valeur de l’original : en lien avec ces discours d’authentification, le thème « Vrai-Faux » demande à la fois d’interroger celles et ceux qui élaborent le discours juridique nécessaire pour faire face aux dérives, mais aussi celles et ceux qui attribuent une valeur aux objets. Nous souhaitons accueillir des propositions abordant le marché de l’art d’hier et d’aujourd’hui, analysant la manière dont le vrai, le faux et toutes les nuances entre ces deux termes modifient, font ou défont la valeur d’une œuvre[11]. Cette problématique engage notamment le domaine de la restauration des monuments historiques et des œuvres. Si, sans le savoir-faire des restaurateurs, soucieux de préserver ou de reconstituer les œuvres dont l’état de conservation est fragile, nombre d’entre elles seraient menacées de disparition, quand est-ce qu’une restauration devient une « hyper-restauration », voire un faux[12]? Où se termine la restauration et où commence la création ?

Je propose une communication :

https://www.festivaldelhistoiredelart.fr/appel-a-contribution-le-vrai-et-le-faux/

[1] Loi du 9 février 1895, sur les fraudes en matières artistiques, JORF du 12 février 1895, page 805, modifiée par l’ordonnance n°2000-916 du 19 septembre 2000, art. 3.

[2] Cette loi définit le faux « à l’apposition d’une fausse signature » et ne s’applique qu’aux œuvres non tombées dans le domaine public. La loi définit la contrefaçon comme une violation des droits d’auteurs, cette dernière dépendant d’autres dispositions du code de la propriété intellectuelle (Articles L. 111-3, L. 332-1, L. 332-3, L. 335-2 et L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle).

[3] François CHAMOUX et al, « Copies, répliques et faux », Revue de l’art, 21, 1973, p. 5–31.

[4] Thierry LENAIN, « Le faux en art et ses valeurs. Repères pour une archéologie », Boris LIBOIS et Alain STROWEL (éd.), Profils de la création, Bruxelles, Presses universitaires Saint-Louis, 1997, p. 177–187.

[5] Stefania CALIANDRO, « Fake Art, entre le contrefait et le contrefactuel », Interfaces numériques, 11 (2), 2022.

[6] Gregory CHATONSKY et Antonio SOMAINI, « Sortir du paradigme de la copie », A.O.C., mercredi 24 janvier 2024.

[7] Bruno Latour et Adam Lowe, « La migration de l’aura ou comment explorer un original par le biais de ses fac-similés », Intermédialités / Intermediality (17), 2011, p. 173–91.

[8] Jean BAUDRILLARD, « Le trompe-l’œil ou la simulation enchantée », De la séduction, Paris, Denoël-Gonthier, coll. « Bibliothèque Médiations », 1981 ; Oscar CALABRESE, L’Art du trompe-l’œil, Follet J.-P. (trad. de l’italien), Paris, Citadelles & Mazenod, coll. « Phares », 2010.

[9] Quentin DELUERMOZ, Pierre SINGARAVELOU, « Explorer le champ des possibles. Approches contrefactuelles et futurs non advenus en histoire », Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine, 2012/3 (n° 59-3), p. 70–95.

[10] Thierry LENAIN, « Le faux en art et ses valeurs … », art. cit.

[11] « [L]’esthétique a cédé la place à l’authentique qui, loin des critères de beauté, fait ou défait la valeur d’une œuvre, tant au regard de l’histoire de l’art, que du marché ». Jean-Claude Marin, procureur général près la Cour de cassation, Allocution prononcée lors du colloque du vendredi 17 novembre 2017, « Le faux en art » : https://www.courdecassation.fr/toutes-les-actualites/2017/11/17/le-faux-en-art

[12] Hélène VEROUGSTRAETE, « Vers des frontières plus claires entre restauration et hyper-restauration », CeROArt, 3 | 2009, [En ligne], URL : http://ceroart.revues.org/index1121.html ; voir également Hélène VEROUGSTRAETE, Roger VAN SCHOUTE et Till-Holger BORCHERT, T.-H.(éd.), Restaurateurs ou faussaires des Primitifs flamands. [Fake or not fake. Het verhaal van de restauratie van de vlaamse Primitieven]. Catalogue d’exposition, Bruges Groeningemuseum 26 novembre 2004-28 février 2005, Gand (Ludion) 2004.

______________________________________

Modalités des interventions

Les interventions du festival de l’histoire de l’art adoptent des formats variés, avec une priorité donnée à des interventions traduisant la recherche en histoire de l’art sous une forme vivante et destinée à un large public.

• Conférence : 1 participant, entre 20 ou 30 minutes maximum,

• Dialogue : 2 participants, entre 40 et 50 minutes maximum,

• Table ronde : jusqu’à 3 participants plus 1 modérateur, durée 1h à 1h10 minutes maximum durée 1h30 maximum incluant le temps d’échange avec le public.

N.B. : Chaque intervention est suivie d’un échange de 10 à 15 minutes avec le public

Dépôt et sélection des propositions

Sont encouragées à candidater conservatrices et conservateurs, restauratrices et restaurateurs, professionnelles et professionnels du monde de l’art, étudiantes et étudiants en master et doctorat, chercheuses et chercheurs, enseignantes et enseignants.

Les candidatures peuvent être envoyées jusqu’au 3 novembre 2024 inclus (avant minuit) via le formulaire dédié : https://www.festivaldelhistoiredelart.fr/appel-a-contribution-le-vrai-et-le-faux/

Un lien n’est pas attendu entre le thème du FHA et le pays invité (l’Autriche), ce dernier ne faisant pas l’objet d’un appel à communication.

Les propositions de communication doivent impérativement être rédigées en français et se présenter sous la forme suivante :

• Titre du projet (80 signes maximum, espaces compris)

• Un résumé (600 signes maximum, espaces compris)

• Une présentation plus longue (3500 signes maximum, espaces compris)

• Un CV + une courte biographie professionnelle

N.B. : Dans le cas des dialogues et des tables rondes, le porteur ou la porteuse du projet doit se désigner clairement dans la proposition d’intervention. Les propositions incomplètes ne seront pas examinées.

L’examen des propositions sera réalisé par l’équipe du festival de l’histoire de l’art accompagné d’un jury issu du comité scientifique du festival de l’histoire de l’art présidé par Madame Laurence Bertrand Dorléac.

leave a comment