Restoration of the Williamsburg Bray School Completed

Opened in 1760, the Bray School is believed to be the oldest surviving building in the United States for the education of Black children. As noted by Lauren Walser in her Preservation article, the school “taught a pro-slavery, faith-based curriculum based on the teachings of the Church of England.” Photo from the Instagram account of Bruce A. deArmond, which foregrounds historic architecture.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The story of the recovery of the Bray School at Colonial Williamsburg is recounted in the latest issue of Preservation (Spring 2025). The formal dedication of the restored building took place on 1 November 2024. It opens to the public this spring. From Colonial Williamsburg:

The Williamsburg Bray School was one of the earliest institutions dedicated to Black education in North America. From 1760 to 1774, teacher Ann Wager likely taught hundreds of students between the ages of three and ten. Students learned the tenets of the Anglican Church and subjects including reading, and for girls, sewing. The Bray School’s deeply flawed purpose was to convince enslaved students to accept their circumstances as divinely ordained. Hidden in plain sight on the William & Mary campus for over 200 years, the Williamsburg Bray School now stands in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area as the Foundation’s 89th original structure. . . .

The Bray School will be used as a focal point for research, scholarship, and dialogue regarding the complicated story of race, religion, and education in Williamsburg and in America.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From Colonial Williamsburg:

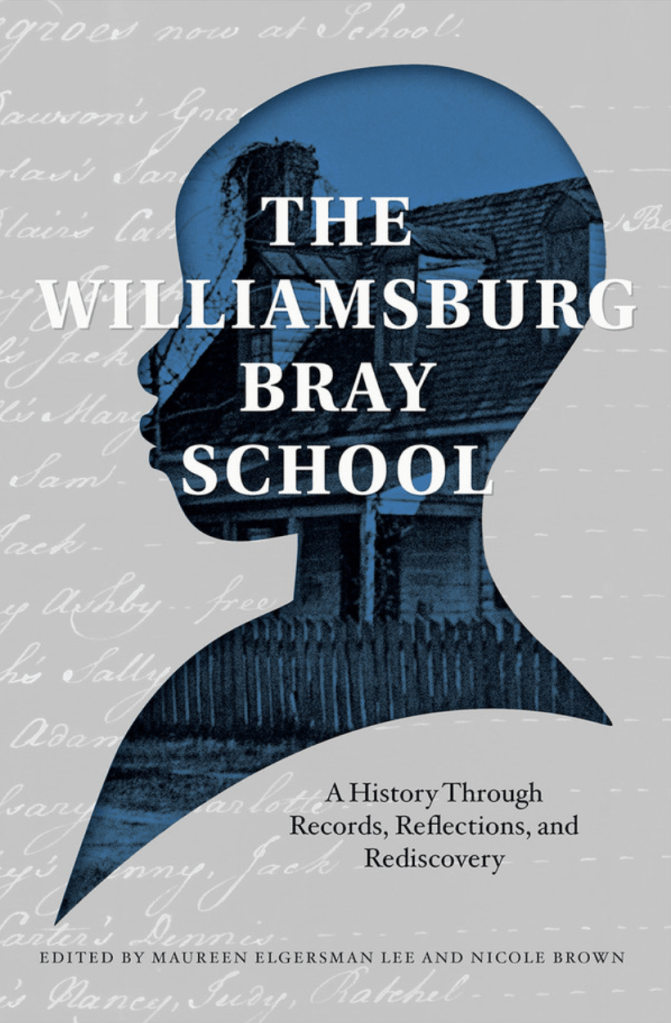

Maureen Elgersman Lee and Nicole Brown, eds., The Williamsburg Bray School: A History through Records, Reflections, and Rediscovery (Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg, 2024), 176 pages, ISBN: 978-0879353032, $20.

Seven letters tracing the arc of the Williamsburg Bray School—from its founding in 1760 to its closing in 1774—provide the foundation for a collection of essays that explore the school’s history and its implications for the enslaved and free Black children who attended. These letters are some of the surviving correspondence between the Williamsburg school’s administrators and the Associates of Dr. Thomas Bray, a London-based Anglican charity whose charge was to minister to what it saw as the spiritual needs of African Americans. The essayists reflect on the evolution of the Williamsburg Bray School, offering a variety of perspectives on the school and the children who attended it. Some pieces reflect years of research and writing on the establishment of the school. Others, including writings from some of the descendants of these students, represent more recent opportunities to reflect on the school and its historical context. In addition to a short history of the school, a map that pinpoints where the children resided in Virginia’s colonial capital, and photographs of the historic letters, the book delves into the 21st-century discovery of the Williamsburg Bray School building, its subsequent move from the William & Mary campus to Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area, and the restoration of the structure that can help tell the complicated story of race, religion, and education in Williamsburg and early America. Author Antonio Bly also shares the poignant story of Isaac Bee, a student at the school who broke the bonds of his enslavement to a Williamsburg planter and rose up from slavery to freedom.

Seven letters tracing the arc of the Williamsburg Bray School—from its founding in 1760 to its closing in 1774—provide the foundation for a collection of essays that explore the school’s history and its implications for the enslaved and free Black children who attended. These letters are some of the surviving correspondence between the Williamsburg school’s administrators and the Associates of Dr. Thomas Bray, a London-based Anglican charity whose charge was to minister to what it saw as the spiritual needs of African Americans. The essayists reflect on the evolution of the Williamsburg Bray School, offering a variety of perspectives on the school and the children who attended it. Some pieces reflect years of research and writing on the establishment of the school. Others, including writings from some of the descendants of these students, represent more recent opportunities to reflect on the school and its historical context. In addition to a short history of the school, a map that pinpoints where the children resided in Virginia’s colonial capital, and photographs of the historic letters, the book delves into the 21st-century discovery of the Williamsburg Bray School building, its subsequent move from the William & Mary campus to Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area, and the restoration of the structure that can help tell the complicated story of race, religion, and education in Williamsburg and early America. Author Antonio Bly also shares the poignant story of Isaac Bee, a student at the school who broke the bonds of his enslavement to a Williamsburg planter and rose up from slavery to freedom.

Maureen Elgersman Lee, director of the William & Mary Bray School Lab, holds both a master’s degree and a doctorate in African American Studies. She is an award-winning professor and author of numerous books and articles on the history of Blacks in the Americas.

Nicole Brown is Graduate Assistant for the William & Mary Bray School Lab and a PhD Candidate in American Studies at William & Mary; she was previously a Program Design Manager at The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. As a first-person historical interpreter, Brown portrays a variety of women including Ann Wager, the 18th-century white teacher at the Williamsburg Bray School, and Monticello’s Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. Brown’s ongoing academic research centers Black literacy in the Atlantic World via interdisciplinary and descendant-engaged scholarship.

Exhibition | Silver from Modest to Majestic

Daniel Garnier, Silver Chandelier, made in London, 1691–97, silver and iron (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1938-42). Fashioned for King William III of England sometime between 1691 and 1697, this chandelier hung at St. James’s Palace in London. It is believed to have been sold for its silver value by King George III when it was seen as outdated. After remaining in private hands for more than a century, it was auctioned in 1924 to William Randolph Hearst, the prominent American newspaperman. Colonial Williamsburg acquired the chandelier shortly before WWII.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release (3 April 2025) for the exhibition:

Silver from Modest to Majestic

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, 24 May 2025 — 24 May 2028

Work is currently underway at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg on a new exhibition featuring more than 120 objects from the museum’s extensive collection of 17th- to 19th-century silver. Silver from Modest to Majestic will be on view in the museum’s newly relocated Mary Jewett Gaiser Silver Gallery, on the main floor of the museum until 24 May 2028.

The exhibition’s scope is wide-ranging, from a 49-lb chandelier made for a monarch to a simple spoon made by a Williamsburg silversmith, all displayed in brilliantly lit cases against dark blue backgrounds. While silver has long been associated with wealth and aristocracy, the items featured in this exhibition were crafted for use in nearly every setting imaginable ranging from churches, classrooms, and kitchens to businesses, battlefields, and bedrooms. One thing that every piece on display has in common is a powerful story. Some are objects of great beauty created with the highest level of skill, while others have lengthy pedigrees. Knowing who made a piece and who used it lets Colonial Williamsburg curators pinpoint that object in a time and a place, and then bring it forward through history, allowing it to tell its tale.

“Collecting objects where we know the ‘who, when, and where’ of their manufacture, plus their provenance, allows us to exhibit silver items which transcend the differences between artistic, historical, and functional,” said Erik Goldstein, Colonial Williamsburg’s senior curator of mechanical arts, metals and numismatics. “These particular objects are the pinnacle of early silver, no matter how humble they may be.”

This new exhibition replaces the museum’s previous silver exhibition, Silver from Mine to Masterpiece, which was on view from 2015 to 2023. While the former exhibition had a larger percentage of British silver, nearly half of the objects on display in the new exhibition are examples of early American-made silver, many of which were created for everyday use by ordinary people. Early colonists originally relied on imported British silver wares, but over time, the innovation, skill, and entrepreneurship of those early American tradespeople resulted in the establishment of a robust and exciting cohort of American silversmiths producing items that were touched by everyone from elite to enslaved individuals.

“Our collection of British silver is justly famous, but our decision to build a collection of American silver terrifically advances the museums’ goal of telling the varied stories of so many different craftspeople and consumers, each of whom influenced the tastes and styles of colonial America,” said Grahame Long, executive director of collections and deputy chief curator.

Punch Ladle, possibly made in Williamsburg, ca.1740–70, silver and wood (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of A. Jefferson Lewis III in memory of Elizabeth Neville Miller and Margaret Prentis Miller Conner, 2023-101; photo by Jason Copes). This worn and lovingly preserved ladle, believed to have been made locally, descended in the Prentis family of Williamsburg.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Visitors to Colonial Williamsburg will experience firsthand how the pieces featured in Silver from Modest to Majestic connect to the lives of Williamsburg’s 18th-century residents. One item in the exhibition—a silver punch ladle, owned by the Prentis family of Williamsburg and passed down in the family for 250 years—served as the model for a reproduction punch ladle created by Williamsburg’s silversmiths that visitors will find in the corner cupboard at the Williamsburg Bray School after it opens to the public in June 2025. Archaeological records show that Ann Wager, headmistress of the Williamsburg Bray School, had punch wares.

“Having the Prentis family’s original ladle gave us a wonderful opportunity to reproduce a piece that we know was used by an 18th-century Williamsburg family and put it in the context of the Bray School where it helps to tell that story,” said Goldstein.

Caddy Spoon, marked by Hester Bateman (1708–1794), London, 1789–90, silver (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Mr. E. Palmer Taylor, 1998-92; photo by Jason Copes). Many now-anonymous British women worked in the silversmithing trade, producing small items like buttons or finishing and polishing larger wares. Standing out is Hester Bateman, who ran a thriving silversmith business after the death of her husband. She specialized in affordable items aimed at the rising middle class. When Bateman retired in 1790, the business was carried on by her sons and one of her daughters-in-law.

Other recently acquired highlights of the silver exhibition include the earliest-known Virginia-made horse racing trophy awarded to a horse named Madison in 1810; an Indian Peace medal struck by the U.S Mint during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency as a diplomatic gift for a Native American chief; and a church communion cup made in Massachusetts around 1670, the earliest piece of American silver in the Foundation’s collection. These pieces will join some of the extraordinary older items from the collection including a cache of British silver made between 1765 and 1771, which was discovered in 1961 in a field near Suffolk, Virginia. While the origins of the buried treasure, and the reason that no one ever returned to retrieve it, remain unknown to this day, this collection is a reminder of the high monetary—and not just aesthetic―value of silver in early America.

The objects on display in Silver from Modest to Majestic represent the work of a few dozen known silversmiths including Paul Revere (1735–1818), a hero of the American Revolution who learned the trade of silversmithing from his father; Myer Myers (1723–1795), the son of a Jewish refugee who became known as the leading silversmith of New York; and Hester Bateman (1708–1794), a female silversmith in London who ran a thriving business after the death of her husband, specializing in affordable items aimed at the rising middle class. Many items in the exhibition are unmarked, made by unknown makers including enslaved silversmiths. Even the items that are credited to known makers could have been made by smiths employed, apprenticed, or enslaved to the master of the shop. To learn exactly how the items in Silver from Modest to Majestic were created, visitors to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg can visit the Silversmith shop in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area where artisan historians preserve the trade by practicing it as their 18th-century counterparts would have.

This exhibition is generously funded by The Mary Jewett Gaiser Silver Study Gallery Endowment. Admission to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg is free.

leave a comment