Call for Papers | Making Early Modern Materialisms, 16th–18th Centuries

From the Call for Papers, which includes the French:

Making Early Modern Materialism(s), 16th–18th Centuries

Fabriquer le(s) matérialisme(s), XVIe–XVIIIe siècles

ENS de Lyon, 30–31 January 2026

Organized by Isabelle Moreau and Jennifer Oliver

Proposals due by 15 June 2025

Bernard Palissy (atelier de) Brique à alvéoles multiples (RMN-Grand Palais, musée de la Renaissance, château d’Ecouen / René-Gabriel Ojéda).

This conference will investigate the contribution made by artisanal and technical practices to materialist thought in early modern scholarly contexts (16th–18th centuries).

Materialism is often presented as a “philosophical discourse produced ‘on the basis of’ or ‘in the name of’ a scientific practice” (Moreau and Wolfe, 2020, our translation), while the history of materialism itself has tended to overlook artisanal know-how, privileging the history of ideas. This situation might be accounted for in two ways. Firstly, any “formulation, from actual observed occurrences, of assertions that cannot be decided on through experimentation” (Andrault, 2017, our translation) thus involves a ‘speculative’ aspect. The role played by theorisation has tended to obscure the practical dimensions of the knowledge being mobilised. Our aim is to reverse this perspective, through attention to the shaping influence of artisanal knowledge and practice on early modern ways of thinking about materiality.

Secondly, the concept of a ‘scientific revolution’ has long been a central tenet in the history of science (Duris, 2016), along with a narrow definition of what ‘science’ is, and the foregrounding of major scholarly figures (Bret, 2016). Like the history of materialism, “the history of science, privileging the study of ideas, has ignored the role of artisans” (Hilaire-Pérez, 2016, translation ours). The recent reconsideration of the of the ‘scientific revolution’ among historians of science—in the field of the life sciences in particular—has opened up a new awareness of the interactions and hybridisations of knowledge between the theoretical and the practical (Hilaire-Pérez, 2016). Applying such a shift in perspective to our study of early modern materialisms is already beginning to bear fruit (see for example the ‘Experimenting the Early Modern Elements’ online conference organised by the Writing Technologies research network, 2021) allowing us to evaluate the impact of artisanal skills and techniques on the various debates on nature and the origins of life.

The role of literary and aesthetic productions in these interactions and hybridisations will also be in focus here. For example, as Frédérique Aït-Touati has recently shown (Théâtres du monde: fabrique de la nature en occident, 2024), real and conceptual theatres (the theatrum mundi and ‘theatre of nature’) were vital sites of exchange and experimentation that allowed for the evaluation and evolution of models of nature.

The period in question—from the 16th to the 18th centuries—is one of many significant scientific and technical discoveries. It also sees the coexistence of very different versions of materialism and even ‘different practices of materialism’ (Pépin, 2012, translation ours). Just as the evolution of science and technology is not linear, materialist discourse is not homogenous. On the other hand, ‘there are many research subjects (reflections on matter, atomism, magic and esotericism, Genesis and theories of the earth, biblical chronology…) that defy religious orthodoxy and draw on scientific research’ (Van Damme, 2016, translation ours). When we attend to know-how and technique, it is striking that the same experiment, the same observation, or the same manipulation of materials can lead to different conclusions and be made to serve diametrically opposed visions of the world. The insistence on empirical experience and autopsy (or seeing for oneself) is also, for that matter, accompanied by repeated warnings about the difficulty of these approaches. Even those with the sharpest eyes and the nimblest fingers will still find, in some cases, that they don’t know a thing, to borrow the expression of Niels Steensen on the anatomy of the brain. The same goes for the micro-anatomy of insects, whose delicate nature, according to Swammerdam, far outstrips the finest cutting edge of his blades. But these limitations on human handiwork do not dampen Swammerdam’s respect for the experience of artisans over scholarly speculations (Duris, 2019). The importance attributed to technical skill and the precision of instruments overturns received ideas of their relationship to knowledge, and calls into question the assumed division of expertise. In order to open up this field of enquiry, we will consider artisanal practices and techniques in their widest sense, in whatever domain (medicine, natural sciences, physics or astronomy).

We especially welcome contributions exploring the following themes:

• Artisanal epistemologies and practical intelligence: the contributions of artisans and practitioners to materialist thought. This theme could be approached from a sociology of sciences perspective, addressing the heterogeneity of actors brought together in experimental contexts and the diversity of practices over the long term of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. One might also revisit the figure of the materialist philosopher with a focus on hybridisation and the mixing of skills, as seen in the ‘scholar-artisans’ brought to light in recent historiography (Hilaire-Pérez, 2016).

• Materialist practices / practices of materialism: anchoring materialist thought within a history of spaces and materials. What are the most important hybrid spaces of knowledge or ‘trading zones’ (Long, 2015) (anatomical theatres, salons, academies, cabinets of curiosity, gardens, etc.)? How are they subject to reappropriation or repurposing? One might also reflect on the textual circulation of materialist thought (from books of secrets to clandestine manuscripts), not least the apparent contradiction between a culture of secrecy and publications aimed at sharing know-how (the notion of ‘useful knowledge’, Berg, 2007; treatises on ‘reduction into art’, Dubourg-Glatigny and Vérin, 2008).

• The materialist tool-box. What practices and skills are most influential in feeding into materialist thought, or, on the contrary, are used by opponents of materialism? Contributions could also reflect on the double paradigm of ‘hand and eye’ in carrying out experiments to support a materialist reading of nature.

• The literary workshop of materialism. It might be productive to consider the incorporation of artisanal images and vocabulary in materialist thought; fictional adaptations of artisanship and artisanal instruments in philosophical fictions; the force of analogy in materialist texts and of literary form in the development of materialist thought.

Abstracts (300 words) should be sent, along with a short CV, to isabelle.moreau@ens-lyon.fr and jennifer_oliver@fas.harvard.edu by the 15th June 2025. Accepted contributors will be notified in July 2025. The conference proceedings are to be published in a special issue of Libertinage et philosophie à l’époque classique (XVIe–XVIIIe siècle).

Organisers

Isabelle Moreau (ENS Lyon) and Jennifer Oliver (Harvard)

Comité scientifique

Isabelle Moreau (ENS Lyon), Jennifer Oliver (Harvard), Kate Tunstall (Oxford), Caroline Warman (Oxford)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Bibliographie Indicative / Indicative Bibliography

Adamson, Glenn. 2007. Thinking Through Craft, Oxford.

Aït-Touati, Frédérique. 2024. Théâtres du monde. Fabriques de la nature en Occident, Éditions La Découverte.

Andrault, Raphaële. 2017. « Leibniz et la connaissance du vivant », dir. Mogens Laerke, Christian Leduc, David Rabouin, Leibniz. Lectures et commentaires, Vrin, p. 171–190.

Berg, Maxine. 2007. « The Genesis of “Useful Knowledge” », History of Science, vol. 14, p. 123–133.

Bert, Jean-François et Lamy, Jérôme. 2021. Voir les savoirs. Lieux, objets et gestes de la science, Anamosa.

Bret, Patrice. 2016. « Figures du savant, XVe–XVIIIe siècle », dir. Liliane Hilaire-Pérez, Fabien Simon, Marie Thébaud-Sorger, L’Europe des sciences et des techniques. Un dialogue des savoirs, XVe–XVIIIe siècle, PUR, p. 95–102.

Charbonnat, Pascal. 2013. Histoire des philosophies matérialistes. Éditions Kimé.

Charbonnat, Pascal. 2006. « Matérialismes et naissance de la paléontologie au 18e siècle ». Matière Première, 1 (1), p. 31–54.

Dubourg-Glatigny, Pascal et Vérin Hélène (dir.). 2008. Réduire en art. La technologie de la Renaissance aux Lumières, Paris, MSH.

Duris, Pascal. 2016. Quelle révolution scientifique ? Les sciences de la vie dans la querelle des Anciens et des Modernes (XVIe–XVIIIe siècle), Éditions Hermann.

Duris, Pascal. 2019. « Changement et préformation. La métamorphose des insectes chez Swammerdam », dir. Juliette Azoulai, Azélie Fayolle & Gisèle Séginger, Les métamorphoses entre fiction et notion. Littérature et sciences (XVIe–XXIe siècle), LISAA éditeur, p. 43–54.

Halleux, Robert. 2009. Le Savoir de la main : savants et artisans dans l’Europe pré-industrielle, Armand Colin.

Hilaire-Pérez, Liliane. 2016. « L’artisan, les sciences et les techniques (XVIe–XVIIIe siècle) », dir. Liliane Hilaire-Pérez, Fabien Simon, Marie Thébaud-Sorger, L’Europe des sciences et des techniques. Un dialogue des savoirs, XVe–XVIIIe siècle, PUR, p. 103–110.

Jacob, Christian (dir.). 2011. Lieux de savoir 2. Les mains de l’intellect, Albin Michel.

Long, Pamela O. 2015. « Trading Zones in Early Modern Europe », Isis, 106–4, p. 840–847.

Mandressi Rafael. 2013. « Le corps des savants. Sciences, histoire, performance », Communications, 92, 2013. Performance – Le corps exposé. Numéro dirigé par Christian Biet et Sylvie Roques. p. 51–65.

Moreau, Pierre-François et Wolfe, Charles T. 2020. « Entretien sur l’histoire du matérialisme », Revue de synthèse, 141 (1-2), p. 107–129.

Mothu, Alain (dir.). 2000. Révolution scientifique et libertinage, Brepols.

Mothu, Alain. 2012. La pensée en cornue. Matérialisme, alchimie et savoirs secrets à l’âge classique, SÉHA/ARCHÉ.

Oosterhoff, Richard J., Marcaida, José Ramón, Marr, Alexander (dir.). 2021. Ingenuity in the Making. Matter and Technique in Early Modern Europe, University of Pittsburgh Press.

Pépin, François (dir.). 2012. Les matérialismes et la chimie. Perspectives philosophiques, historiques et scientifiques, Éditions Matériologiques.

Roberts, Lissa, Schaffer, Simon, Dear, Peter (dir.). 2007. The Mindful Hand: Inquiry and Invention from the Late Renaissance to Early Industrialisation, Amsterdam.

Smith, Pamela H., 2014–. The Making and Knowing Project, Columbia University, https://www.makingandknowing.org/.

Smith, Pamela H., Meyers, Amy R. W., Cook, Harold J. (dir.). 2014. Ways of Making and Knowing. The Material Culture of Empirical Knowledge, The University of Michigan Press.

Van Damme, Stéphane. 2016. « Les sciences à l’épreuve du libertinage », dir. Liliane Hilaire-Pérez, Fabien Simon, Marie Thébaud-Sorger, L’Europe des sciences et des techniques. Un dialogue des savoirs, XVe-XVIIIe siècle, PUR, p. 473–485.

Waquet, Françoise. 2015. L’ordre matériel du savoir. Comment les savants travaillent, XVIe–XXIe siècle, CNRS Éditions.

Call for Papers | Image and Text in Travel Narratives

From the Call for Papers:

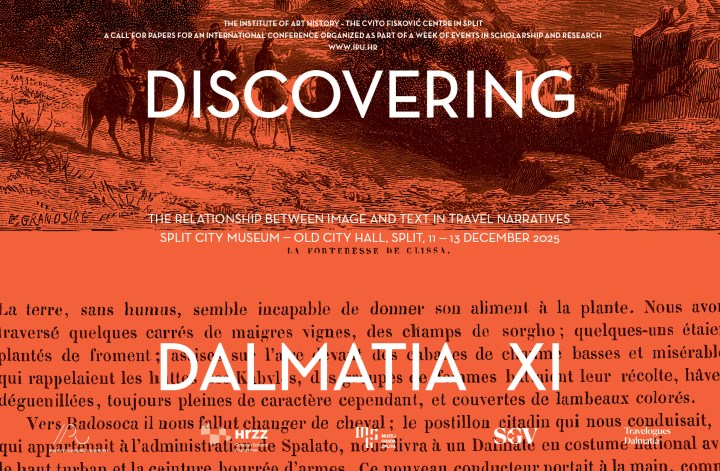

Discovering Dalmatia XI

The Relationship Between Image and Text in Travel Narratives

Split, 11–13 December 2025

Proposals due by 15 July 2025

Keynote Speaker: Heather Hyde Minor, Professor of Art History, Concurrent Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures, University of Notre Dame

Travelogues take shape through the wide range of travel experiences recorded in books, periodicals, diaries, letters, drawings, paintings, prints, and photographs. They represent invaluable historical and cultural sources in which textual and visual narratives are often intertwined in order to convey complex impressions of places, people, and cultural heritage in as much detail as possible. In forming such responses, artist-authors are engaged in an intense dialogue with place, often leaving behind experiences recorded in both text and image. These documents of experience strongly mark, in turn, the spaces they mediate, often becoming models themselves for future travel writers. Among those regions recorded in travel narratives, Dalmatia occupies a significant place: often depicted in this rich relationship between image and text, these together shape a layered perception of its complex identity.

This year’s Discovering Dalmatia conference in Split is specifically dedicated to exploring the ways in which these two forms of representation intertwine within the travel genre. The focus will be on the dynamic relationship between words and images: on the function of visual elements (illustrations, graphics, photographs) within, and alongside, the travel text, and on how—together—they shape the narrative tone of the travelogue and the perception of a particular place. We encourage presenters to think about diachronic perspectives—which follow changes in the relationship between image and text over time—as well as the dialogical nature of this interaction, and how this might raise questions about authorship, credibility, cultural translation, and intermediality in travel literature.

The visual component of the travelogue has often worked to confirm the credibility of the text or to attract a reading audience fascinated by the ‘exotic’ southeastern edge of Europe. At the same time, images bring their own visual rhetoric—sometimes supporting and sometimes replacing the written narrative. Theoretical approaches that consider image and text not as parallel, but as interdependent semiotic systems, are necessary for understanding the specifics of the travel genre. We therefore invite contributions that offer theoretical reflections on this relationship, or which discuss concrete case studies, particularly those concerning travel accounts about Dalmatia and within the intense period of study trips to the region from the eighteenth to the mid-twentieth century.

The conference aims to bring together scholars from different disciplines—the history of art, architecture, literature, visual culture, anthropology, and media studies—to reflect on how the interrelationship between image and text in travelogues contributes to the construction of meaning, memory, and cultural identity. Dalmatia, with its rich presence in the European travel writing tradition, offers particularly fertile ground for such research.

We ask participants to reflect on two central questions:

• How do visual and textual representations of places, particularly Dalmatia, work together in shaping perceptions of space, heritage, identity, and otherness?

• What historical and conceptual models help us understand the relationship between image and text in travel literature?

We welcome proposals that examine a wide range of travel material that combines text and image. It is our hope that the conference will contribute to a deeper understanding of various aspects of the interplay of image and text, to promote rich reflections on Dalmatia’s place in the European cultural imagination, as well as to defining the travelogue as an autonomous, multidisciplinary, and multimedia practice. Proposals for 20-minute papers, consisting of a 250-word abstract and a short CV in Croatian or English, should be sent via email as a PDF attachment to discoveringdalmatia@gmail.com by 15 July 2025.

Registration will take place on the evening of the 10th of December, the closing address will take place on the 13th of December, and the hosts will organise coffee and refreshments for conference participants during breaks. No participation fee will be charged for this conference. The organisers do not cover travel and accommodation costs. The organisers can help participants to find reasonably-priced accommodation in the historic city centre. Papers and discussions will be conducted in English. The duration of a spoken contribution should not exceed 20 minutes. Presentations will be followed by discussions. We propose to publish a collection of selected papers from the conference.

Scientific Committee

Joško Belamarić (Institute of Art History – Cvito Fisković Centre Split)

Davide Lacagnina (University of Siena, School of Specialization in Art History)

Tod Marder (Rutgers University, Department of Art History)

Katrina O’Loughlin (Brunel University London)

Cvijeta Pavlović (University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Department of Comparative Literature)

Marko Špikić (University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Department of Art History)

Ana Šverko (Institute of Art History – Cvito Fisković Centre Split)

Elke Katharina Wittich (Leibniz Universität Hannover)

Sanja Žaja Vrbica (University of Dubrovnik, Arts and Restoration Department)

Organizing Committee

Joško Belamarić (Institute of Art History – Cvito Fisković Centre Split)

Tomislav Bosnić (Institute of Art History – Cvito Fisković Centre Split)

Ana Ćurić (Institute of Art History)

Katrina O’Loughlin (Brunel University London)

Ana Šverko (Institute of Art History – Cvito Fisković Centre Split)

Sanja Žaja Vrbica (University of Dubrovnik, Arts and Restoration Department)

The conference is organized as part of the Croatian Science Foundation project Travelogues Dalmatia IP-2022-10-8676.

leave a comment