Online Talk | Alexandra Kirtley on the Work of Black Artisans

As noted at Events in the Field, administered by The Decorative Arts Trust:

Alexandra Kirtley | Thomas Gross in Context: Black Artisans in Early Philadelphia

Online, DAR Museum, 9 September 2025, noon (Eastern Time)

Thomas Gross Jr., Double Chest (Chest-on-Chest), made in Philadelphia, 1805–10, mahogany, tulip poplar, and yellow pine with brass, 83 inches high (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1983-167-1a,b).

The work of cabinetmaker Thomas Gross (1775–1839) provides the centerpiece to the study and understanding of Black artists and artisans who contributed to the fabric of the prolific art community in early Philadelphia. This richly illustrated talk will share the documentary evidence of the names of those people as well as the work they made, from silversmiths, upholsterers, potters, and cabinetmakers to painters like David Bustill Bowser and his seamstress wife Elizabeth Harriet Stevens Gray Bowser.

Please note that this event is taking place online only; Alexandra Kirtley will not be present at the DAR Museum.

Registration is available here»

Alexandra Kirtley is the Montgomery-Garvan Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Call for Papers | Religious Enlightenments: Spirituality and Space

This session is part of next year’s EAHN conference; the full Call for Papers is available here:

Religious Enlightenment(s): Spirituality and Space in the Long Eighteenth Century

Session at the Conference of the European Architectural History Network, Aarhus, 17–21 June 2026

Chair: Demetra Vogiatzaki

Proposals due by 19 September 2025

In recent decades, the traditional view of the Enlightenment as a period of radical secularization and material monism has been substantially revised. Scholars such as David Sorkin, Jonathan Israel, Catherine Maire, Paschalis Kitromilides, and Robert Darnton have emphasized the enduring and multifaceted role of religion and spirituality—across both institutional and popular expressions—in shaping the politics, culture, and everyday life of the long eighteenth century. Architectural surveys of the period, however, have often lagged behind this historiographical turn, overlooking the importance of religion and spirituality in the shaping of Enlightenment culture, limiting their scope to a strictly formal analysis, or dismissing non-sanctified spaces and experiences of spirituality as anomalies in the progressive, inevitable ‘disenchantment’ of the world.

In recent decades, the traditional view of the Enlightenment as a period of radical secularization and material monism has been substantially revised. Scholars such as David Sorkin, Jonathan Israel, Catherine Maire, Paschalis Kitromilides, and Robert Darnton have emphasized the enduring and multifaceted role of religion and spirituality—across both institutional and popular expressions—in shaping the politics, culture, and everyday life of the long eighteenth century. Architectural surveys of the period, however, have often lagged behind this historiographical turn, overlooking the importance of religion and spirituality in the shaping of Enlightenment culture, limiting their scope to a strictly formal analysis, or dismissing non-sanctified spaces and experiences of spirituality as anomalies in the progressive, inevitable ‘disenchantment’ of the world.

This session invites papers that explore the political, social, and aesthetic resonances of sacred space in the Enlightenment. From little studied state-sponsored and public programs, all the way to local, vernacular and/or intimate expressions of sacrality, how did architecture and the built environment broad-writ reflect or resist evolving religious identities, dogmatic debates, and communal rituals? Following the lead of such studies as Karsten Harries’ work on Bavarian Rococo Churches, or Ünver Rüstem’s reading of Ottoman Baroque forms and their entanglement with local Christian and Islamic traditions, the goal is to integrate formal analysis with socio-politically embedded approaches, foregrounding spatial practices that have often been overlooked in dominant narratives of Enlightenment architecture.

Topics might include, but are not limited to:

• Patronage networks and sacred architecture in diasporic or commercial communities, as in the port towns of the Mediterranean.

• Reused or re-interpreted religious sites in post-Jesuit or post-missionary contexts (i.e. in the Ethiopian highlands).

• Syncretic religious spaces shaped by colonial conquest and negotiation, as for example, in and around the settlements of New France.

• Ephemeral structures associated with pilgrimage, mourning, or ritual performance.

• Staged sacred environments in Enlightenment theatre, festivals, and visual culture.

• Interfaith collaborations and architectural vocabularies in multi-confessional settings.

We particularly encourage proposals that attend to sacred experiences and spatial practices beyond the bounds of formal religious architecture, and that consider the ways in which spiritual expression operated through, and resisted Enlightenment-era aesthetics. Abstracts are invited by 19 September 2025, 23.59 CET. Abstracts of no more than 300 words should be submitted directly to the chair, along with the applicant’s name, email address, professional affiliation, address, telephone number, and a short curriculum vitae.

Chair

Dr. Demetra Vogiatzaki, gta/ETH Zurich

vogiatzaki@arch.ethz.ch

The Burlington Magazine, July 2025

The long 18th century in the July issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 167 (July 2025)

e d i t o r i a l

Maria van Oosterwijck, Vanitas stilleven, ca. 1675, oil on canvas (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum).

• “The Gallery of Honour,” p. 635. The gallery of honour in the heart of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, has recently welcomed an impressive painting to its walls: Vanitas still life by Maria van Oosterwijck (1630–93). In a compelling sense the artist has long had a place in galleries of honour, as works by her were acquired by Emperor Leopold I, Louis XIV of France, and Cosimo III de’ Medici of Tuscany.

r e v i e w s

• Christian Scholl, “Germany’s Celebration of Caspar David Friedrich’s 250th Anniversary,” pp. 694–701.

In Germany, the 250th anniversary of Caspar David Friedrich’s birth was celebrated with a series of exhibitions. Key among them were those organised by the three museums with the most extensive holdings of the artist’s work: the Hamburger Kunsthalle, the Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. All three focused on stylistic, iconographic and technical aspects of the artist’s work rather than on Friedrich’s life, and each in its own way has thrown fresh light on his complex and enigmatic art.

Luis Egidio Meléndez, Still Life with Figs, ca. 1760, oil on canvas (Paris: Musée du Louvre, on view at the Musée Goya, Castres).

• Robert Wenley, Review of the exhibition Wellington’s Dutch Masterpieces (Apsley House, London, 2025), pp. 713–15.

• Christoph Martin Vogtherr, Review of the exhibition Corot to Watteau? On the Trail of French Drawings (Kunsthalle Bremen, 2025), pp. 715–18.

• Elsa Espin, Review of the exhibition Le Louvre s’invite chez Goya (Musée Goya, Castres, 2025), pp. 718–20.

• John Marciari, Review of the exhibition Picturing Nature: The Stuart Collection of 18th- and 19th-Century British Landscapes and Beyond (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2025), pp. 720–22.

• Kee Il Choi Jr., Review of the exhibition Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, pp. 722–25.

• Deborah Howard, Review of Mario Piana, Costruire a Venezia: I mutamenti delle tecniche edificatorie lagunari tra Medioevo e Età moderna (Marsilio, 2024), pp. 732–33.

• Isabelle Mayer-Michalon, Review of Christophe Huchet de Quénetain and Moana Weil-Curiel, Étienne Barthélemy Garnier (1765–1849): De l’Académie royale à l’Institut de France (Éditions Faton, 2023), pp. 737–39.

Call for Papers | CAA 2026, Chicago

I’ve highlighted here a selection of panels related to the eighteenth century; but please consult the Call for Papers for additional possibilities. –CH

114th Annual Conference of the College Art Association

Hilton Chicago, 18–21 February 2026

Proposals due by 29 August 2025

Architectural Utopias Redux

Chair: Demetra Vogiatzaki (ETH Zurich)

Can utopia still be a meaningful framework for researching and teaching architecture in a time of ecological and political crisis? Since the Enlightenment, architectural utopias have often shed their emancipatory potential, functioning instead as instruments of capitalist expansion, settler colonialism, and modernist abstraction–so Manfredo Tafuri and Anthony Vidler, among other architectural historians, have claimed. Yet beneath the failed promises of the architectural ‘avant-gardes’ lie counter-histories of resilience—’rear-guard’ efforts that challenged dominant spatial paradigms while restoring equity in their present. This panel invites a rethinking of architectural utopianism by turning attention to those who resisted, subverted, or reconfigured utopian ideals from the margins. What insights can be gained by examining utopia not as a formal project of radical innovation, but as a practice of community endurance and revolt?

We welcome papers that explore the spatial practices of feminist, decolonial, spiritual, and other collectivist movements challenging the exclusions embedded in dominant utopian narratives. These may include intentional communities, grassroots infrastructures, pedagogical experiments, or speculative practices grounded in marginalized worldviews. Submissions may address any historical period, but special attention will be given to work that situates premodern, early modern, or underrepresented geographic contexts within broader debates on utopianism. We also encourage contributions proposing alternative methodologies for teaching utopias in architecture—through archives, oral histories, literary or material culture. By centering the ‘rear-guard’ of architectural history—those whose visions have often been erased, or dismissed—we hope to reimagine utopia not as an unreachable blueprint, but as a lived and ongoing project of resistance.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Art and Architecture vs. Environment: Failure, Redesign, and Innovation in the Early Modern Iberian World (Society for Iberian Global Art)

Chairs: Rebecca Yuste (Columbia University) and Amy Chang (Harvard University)

The history of the early modern Iberian world is strewn with stories of architectural ambition and engineering innovation that seek to defy, overcome, or restructure extant environmental conditions. Land-reclaiming and flood-controlling projects represent a major thematic in this period, from Regi Lagni in Naples to the desagüe of Mexico City, as do seismic-responsive architectures such as the famous Earthquake Baroque in the Philippines and Guatemala, and as well as post-earthquake architectures in Sicily and Lisbon. Early modern architecture and engineering is often characterized by new boldness of ambition in responding to, attempting to overcome, or intending to change environmental conditions, it often yields cycles of loss, failure, and reiteration, until new technics are achieved.

This panel seeks to learn from stories of architectural and infrastructural failure, innovation, and redesign, especially as it relates to practices of colonialism, from across the Iberian world. We invite papers that seek to complicate the narrative of architectural domination on the land and landscape and search for cases that focus on moments of disjunction and defeat in the face of environmental factors, and the struggle to respond. Papers may examine the consequences of incomplete knowledge of landscapes, ecologies, and materials, and the cases under consideration may be architectural works that were unfinished, hypothetical, never realized, or rebuilt after confronting natural disasters and misunderstandings of ground conditions. We also welcome papers on artworks representing knowledge of materials and environments; moments of disaster, engineering, and rebuilding; or changes in understandings of nature and environment.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Bad Government: Art and Politics in the Eighteenth Century (American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies)

Chair: Amy E. Freund (Southern Methodist University)

How did art, architecture, and visual and material culture in the long eighteenth century perpetuate or resist objectionable forms of government? This panel will consider how the arts were weaponized both by political leaders to shore up their regimes and by their critics to bring those regimes down. Potential topics include but are by no means limited to: the arts of the eighteenth century’s revolutions and counterrevolutions, the enlistment of the visual arts to justify, perpetuate, and resist colonialism, popular media and propaganda, the building and destruction of palaces, monuments, and other public-facing forms of art, artists as political actors, private and domestic forms of artistic control and contestation, portraits of rulers and political figures, sacred art in the service of secular struggles, and the mobilization of scientific illustration for political ends.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Centering the Margins: Art and Identity beyond the Colonial American Metropoles

Chairs: JoAnna Reyes (Arizona State University) and Carlos Rivas (The Ohio State University)

This panel investigates the rich artistic traditions of colonial cities in the Americas that developed outside imperial capitals. While metropolitan centers such as Mexico City and Lima have long dominated narratives of colonial art, cities like Antigua (Guatemala), Ouro Preto (Brazil), Cuzco (Peru), and Popayán (Colombia) cultivated distinctive visual cultures that reflected complex interactions among European, Indigenous, African, and mestizo communities. These extra-metropolitan locales were not peripheral but central to the formation of regional artistic identities, often serving as hubs of innovation, adaptation, and resistance.

Panelists will explore how visual culture and aesthetic preference were transformed in these cities through localized interpretations, responding to local materials, labor networks, and spiritual traditions. Religious architecture and devotional arts—especially those commissioned for monasteries, cathedrals, and mission churches—may serve as a lens to examine both the imposition and reinterpretation of colonial ideologies. The panel also considers the importance of artisan networks and the movement of artists, artworks, and raw materials across colonial territories, illuminating the transregional dynamics that shaped local production.

In tracing these developments, the panel foregrounds how artistic production in these cities negotiated colonial authority while fostering creole and Indigenous expressions of identity. By centering these often-overlooked locales, this panel seeks to expand the geographies of colonial art history and enrich our understanding of artistic agency in the Americas.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Freedom, Fugitivity, and Revolt in the Global Netherlandish World, 1500–1800

Chairs: Arianna Ray (Northwestern University) and Kathleen DiDomenico (Washington University in St. Louis)

This session explores the distinct but related notions of freedom, fugitivity, and revolt in art of the global Netherlandish world, ca. 1500–1800. Freedom, understood as the state of being unencumbered by restrictions, restraints, or oppression, is often seen as a defining feature of the early modern Netherlands, where political revolt, religious reform, economic endeavor, and artistic experimentation resulted in newfound freedoms for certain populations. But alongside these often precarious freedoms, there remained hierarchies of power that kept people locked in systems of repression, subjugation, and exploitation. In response, historical subjects turned to strategic practices of fugitivity and revolt, both overt and subtle, in an effort to resist domination and create alternative spaces of personal and collective liberty. This panel will examine concepts of freedom/unfreedom capaciously, as a labor status, an artistic practice, and a theoretical question. We build upon the insights of scholars within and beyond art history, including Saidiya Hartman, Neil Roberts, and Tina Campt, among others. We welcome interdisciplinary and methodologically innovative approaches, particularly those engaging with Black studies, Indigenous studies, gender and queer theory, and decolonial critique.

Potential topics include:

• Depictions of forced labor including slavery, serfdom, and indentured servitude

• Depictions of fugitives, maroons, revolutionaries, and diasporic communities

• Representations of individual and collective acts of resistance

• Mapping spaces/sites/locations of freedom, fugitivity, and revolt

• Objects made by forced laborers or those who achieved freedom

• Visual culture around rebellions and uprisings

• Artistic freedom and creativity

• Coded imagery and subversive aesthetics

• Absences in the archive and/as fugitivity

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Garden and its Discontents / Discontents in the Garden

Chairs: Xiaoyao Guo (Princeton University) and Chenchen Yan (Princeton University)

As locus amoenus and paradise lost, the garden has been a place of ambivalence since the start of human civilization. Positioned uneasily between landscape and architecture, it is also one of the most powerful topoi through which to tame, emulate, and (re)construct nature. This panel revisits the long and rich histories of the garden and investigates its ambivalence, here reformulated as “discontents,” through various cultural historical mediations.

Motivated by Sigmund Freud’s famous essay “Civilization and its Discontents” on the irreconcilable clash between individual instincts and societal regulations, this panel aims to reread the garden into its concrete sociohistorical textures. Furthermore, drawing from the precise translation of the essay’s original title, “The Discontent in Civilization,” this panel approaches the garden as a contested site between ideologies, discourses, and sensibilities in which contradictions and antagonisms are inherently constitutive of its construction. From the Venetian terraferma to the Japanese bonsai, from the English picturesque to the American wilderness, the garden addresses specific questions of its times, and challenges its presumed harmony and unity: What are the discontents housed within the seemingly serene Elysium? What perceptual and conceptual tensions need to be identified, what hierarchies undone? We welcome submissions on the discontents of/in the garden across cultures and histories. This “comparative-global” approach, we hope, would highlight in turn the cultural-specificity and social constructedness of the garden. Articulating these discontents, then, would offer valuable insights into the binaries of art-science, nature-culture, self-other urgent to today’s ecologically conscious world.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Hybridity, Adaptability, and Exchange during the Long Eighteenth Century: Producing Global Aesthetics in Decorative Art and Design (Historians of Eighteenth-Century Art and Architecture)

Chairs: Zifeng Zhao (University of Cambridge) and Alisha Ma (London School of Economics and Political Science)

Over the long eighteenth century (c. 1689–1815), the decorative arts and design underwent profound change via global diffusion of objects, techniques, and knowledge. Although global artistic exchange has shaped cultural landscapes for centuries, this particular period saw the creation of new aesthetic paradigms and fostered cultural discourses regarding notions of cultural agency, identity, and authenticity. This session examines the making of global aesthetic traditions and practices in the long eighteenth century by closely interrogating the dynamics of cross-cultural hybridity, adaptability, and exchange along with their usefulness as art historical concepts. Furthermore, the session will illustrate how the evolution of artistic traditions shaped visual, material, sensorial, and political landscapes across the early modern world.

We invite contributions that address how individuals and collectives responded to cross-cultural interactions, creatively adapting and transforming these influences into novel, hybrid forms. We welcome papers from diverse geographies that consider how decorative art and design functioned as crucial contact zones where local traditions were continuously reimagined through exchange as well as resistance. For example, Indian artisans adapted traditional cotton textile designs for European tastes, while European potters such as the Delft and Meissen factories experimented with new technologies to produce ceramics in competition with Chinese porcelain. Meanwhile, Colonoware pottery was produced by enslaved Africans in North America from a combination of African traditions, local resources and practical demands. Ultimately, this discussion will deepen scholarly understanding of the role played by the decorative arts in producing global visual and material cultures during the long eighteenth century.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Is There a Native American Art History Canon? Is It a Good Idea?

Chairs: Karen Kessel and Alicia Lynn Harris (University of Oklahoma)

While the framing of art history survey courses has gradually shifted from a core focus on Western Civilization emanating from Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean regions to a more global view, the North American continent remains marginalized. Some American art history texts now incorporate Native American works into their narrative, but do Native Americans identify with being part of the United States’ cultural history? Current textbooks for Native American art focus disproportionately on the post-contact era with minimal coverage of the millennia that came before. Why? Archaeologists, who do not generally prioritize artistic achievement in their research, have been the main contributors to studies of the pre-contact era in North America. Given recent contributions to the field from an increase in Native scholars working in museums and academic institutions, this panel seeks to understand and help define the current best practices for teaching Native American art history. We invite papers that assess what can and should be shared, when, and who has authority over cultural domains, along with consideration of what themes, ideas, artworks, and frameworks are currently considered best practices to enhance the appreciation and understanding of Native American art history.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Landscape, Materiality, and Representation in the Long Nineteenth Century

Chair: Noam Gonnen (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev)

This session invites contributions that investigate the entangled relationships between landscape, materiality, and representation in the long nineteenth century. While landscape has often been examined through symbolic, nationalistic, or pictorial frameworks, this panel foregrounds its material dimensions—both as subject and substance—and asks how they shaped artistic and cultural production during this transformative period. How did the physical qualities of land, earth, and environment inflect visual representation? What tensions emerged between landscape as material presence and landscape as mediated image?

Bridging art history, material and visual culture, human geography, and environmental humanities, this session seeks to integrate phenomenological approaches (Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger, Casey), material and object-oriented ontology (Bennett, Harman), and geographical theory (Ingold) with close visual and historical analysis. We are particularly interested in how the materiality of land—its textures, substances, and transformations—was registered, abstracted, or resisted in the practices of representation across diverse geographies, media, and artistic traditions during this period.

Contributors might consider:

• The material construction of landscape images: grounds, supports, pigments, and surfaces

• Representing geological time, land use, or extraction industries

• Earth as medium: pigment, sediment, and organic matter in artistic practice

• Artistic responses to ecological degradation

• Indigenous and non-Western modes of representing land and territory

• The role of materiality in 19th-century cartography or land surveys

• The visual rhetorics of land ownership, enclosure, and displacement

• Intersections of land, labor, and class in visual culture

We welcome proposals engaging with both canonical and understudied works that rethink landscape through its material and representational operations.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Let’s Get Metaphysical: Rethinking the Empiricism of British Art (Historians of British Art)

Chair: Douglas R. Fordham (University of Virginia)

Histories of British art rarely ask metaphysical questions. More common are narratives in which the empiricism of Locke and Newton inspired artists to draw and paint the material world “after the life”. But how feasible was it for British artists to bracket metaphysical questions out of their work? As Eugene Thacker noted, “‘Life’ is a troubling and contradictory concept…. Every ontology of ‘life’ thinks of life in terms of something-other-than-life [which] is most often a metaphysical concept, such as time and temporality, form and causality, or spirit and immanence.”

What, if anything, enabled British art to transcend its base materiality? Should paintings ever be more than mimetic ‘pictures’ of the material world, and if so, what beliefs, ideas, or eternal propositions did they invoke? We have grown accustomed to thinking of British artists as post-Reformation iconoclasts who embraced an empirical view of the world. Painting is treated like a mode of critique in which artists contributed to the disenchantment of the modern world. This panel is interested in British art, in any medium and from any period, that refused to settle for mimetic realism. While altarpieces, funerary monuments, and the spiritual visions of William Blake immediately come to mind, papers could interrogate the ‘naturalism’ or ‘lifelikeness’ of J.M.W. Turner, the Pre-Raphaelites, Walter Sickert, and a great deal more.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Materiality and the Reception of Ancient Objects

Chairs: Stephanie Rose Caruso (The Art Institute of Chicago) and Andrea Morgan (The Art Institute of Chicago)

Ancient Mediterranean objects typically survive in a fragmented state, and their reception, particularly sculpture, has shifted over time. Seventeenth-century artists worked to return fragmented ancient sculptures to a ‘whole’ or ‘complete’ state. Yet, in 1803, Antonio Canova refused Lord Elgin’s proposal to restore the Parthenon marbles, fearing it would damage their original condition. Thus, there was an eventual shift in the perception of the fragment—no longer ‘incomplete’, it possessed an “age value” as Alois Riegl later theorized. With the discovery of ancient textiles in Egypt in the second half of the nineteenth century an opposite approach to the fragment developed. Despite the fact that one might discover a ‘complete’ ancient textile, it was rarely retained; rather, it was cut into as many pieces as possible. Not perceived as fine art, their value instead stemmed from their ability to transmit patterns.

This panel aims to explore the reception, manipulation, restoration, or destruction of ancient objects from the Renaissance through the end of the nineteenth century. We invite papers that investigate whether the specific materiality of ancient objects makes them more vulnerable or resistant to later intervention. Topics can include the exploration of the concept of in/completeness in relation to changing tastes and theoretical divisions between the fine and applied arts; in/completeness and restoration in relation to aesthetic and historical integrity; and the exploration of pastiches. We seek contributions that look closely at surviving objects to extrapolate new ways of thinking about the reception of ancient art.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Modes of Inscription

Chairs: Erica DiBenedetto (The Museum of Modern Art) and Charles Kang (Rijksmuseum)

Adding language to an object takes many forms and has a long history. It can be done, for example, by the maker of an object as an integral part of generating a work. It can be done by others–and often at a later date–as an addition, an intervention, or even an accident irrelevant to the work. While the modes of inscription might differ from case to case, the voice behind the inscription can bestow a sense of authority in the life of an object. It can also trouble its interpretation. Rather than framing the idea of inscription in terms of word/image relations, this CAA session understands the act of adding language to an object fundamentally as a mediation. Although found across many periods, geographies, and mediums, the practice of inscription has not received sufficient attention from a global and transhistorical perspective. Panelists are therefore invited to examine instances of inscription specific to their respective fields, using their expertise to offer new questions and theoretical considerations about the phenomenon. The common aim will be to consider how such mediations help us think differently about conceptions of authorship, meaning, and possession across time and space.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Nature in Indigenous Arts of the Ancient and Colonial Americas

Chairs: James Cordova (University of Colorado Boulder) and Angélica J. Afanador-Pujol

The culture-nature divide inherent in European epistemologies and cosmologies contrasts sharply with Indigenous American perspectives, which emphasize interconnectedness over discordance between humans and the natural world. Before European colonization, Indigenous ontologies profoundly shaped the roles of the natural world in their artistic expressions. These beliefs are often evident in the materials chosen for creations, representations of plants, animals, deities, and other sentient beings, as well as the design and layout of cities. In addition to the colonial exploitation of Indigenous peoples and the natural world, the imposition of European epistemologies elicited diverse responses, ranging from outright resistance to selective appropriation, partial acceptance, and full assimilation. This session invites papers that examine the critical roles nature and the environment played in Indigenous creative expressions from ancient to colonial times (c. 1400 BCE – 1825 CE) across North America, Mesoamerica, the Caribbean, Amazonia, and the Andes.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Pigments and Praxis in the Early Modern Period

Chairs: Annie Correll (New York University) and Gerrit Albertson (Art Institute of Chicago)

Early modern and contemporary sources alike have compared artists’ workshop practices with those of alchemists, as they ground and mixed their pigments with binding media, experimenting with additives and proportions to develop paints with particular viscosities and opacities. Technical studies have further proven the specialized attention that early modern artists paid to their pigments. Hendrick Avercamp used smalt between layers of lead white, diffracting and absorbing light to achieve icy, atmospheric skies in his winter scenes; Frans Hals experimented with indigo in the sashes of his 1627 Haarlem Civic Guard portraits despite contemporary concerns about its discoloration; and Rembrandt developed a signature lead-white paint, adjusting its rheological properties for use in his impasto. This panel seeks to bring together the technical and the art historical to consider pigments not just as agents for color, but for artistic experimentation and cultural significance. We especially welcome joint papers by early modern art historians and conservators or scientists.

Questions addressed may include:

• What can be revealed by tracing the trade routes along which pigments travelled?

• How did environmental or geological factors affect the raw materials of natural pigments? How were they harvested, processed, and made into paint?

• Who played a role in this process? What were the socio-economic or power dynamics at play?

• How did the use of pigments conform to or converge from art theory?

• How did artists experiment to achieve desired color, light, or textural effects?

• What can pigments tell us about the perceived value or purpose of a painting?

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The Margins and Backgrounds of Portraits

Chairs: Joseph Litts (Princeton University) and Michael Hartman (Dartmouth College – Hood Museum)

Portraiture studies have traditionally focused on faces, clothing, and accessories as sites of creating and stabilizing identity within art. Layers of oil paint, pastel dust, and engraved ink articulate race, gender, class, and kinship networks on a scale ranging from jewelry miniatures to life-size replicas. Scholars have demonstrated how these representations surrogated for distant power, how collections and exhibitions were political statements, and how portrait iconoclasm could be broadly ideological rather than personal.

However, what happens behind and around the body? This facet of portraiture remains an open field. Our panel thus invites papers that examine the margins and backgrounds of portraits. These spaces vary from roundels or planes of color, to classicizing scenes or imaginary gardens, to draperies or architectural structures. As much as standardized formulas and techniques have developed for the face itself, the (back)ground has been curiously resistant to such strategies. This panel asks what do these diverse environments—a visualized “habitus,” to borrow from Bourdieu—contribute to the portrait? How might painterly surroundings trouble notions of identity and modernity? For group portraits and conversation pieces, how does setting provoke or dismiss relationality? Do specific display or exhibition contexts become extended backgrounds for portraits, especially with sculptures? Ultimately, how do the edges, however they might be defined, (re)frame our understanding of the key genre of portraiture? In addition to paying close attention to the borders and liminal spaces of portraiture as traditionally understood, we also welcome papers that trouble the definitions of portraiture itself through close attention to context.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Ungrading Art History

Chairs: Jessy L. Bell (Northwestern University) and Brian T. Leahy (Montana State University Billings)

The art history classroom has long been distinguished by harsh grading, steep learning curves, and high-stakes memorization. However, in the current era of generative AI and legislative attacks on the humanities, there is an urgent need for art history to reexamine its pedagogical foundations to better fulfill its most vital role: teaching critical thinking about images. Recent pedagogical movements variously called ungrading, contract grading, or de-grading, backed by research in the science of teaching and learning (Alfie Kohn, Susan D. Blum, Joshua R. Eyler, Jesse Stommel, and others) challenge the predominance of punitive strategies for evaluating student learning. Instead, these studies propose approaches that develop students’ intrinsic desires for learning through evaluative feedback, progress-based assessment, self-reflection, project-based learning, and other methods. This panel asks how art history might also reimagine its pedagogical and evaluative practices beyond grades—or conventional assessments more broadly—not only to deepen student engagement, but also to reclaim the radical potential of looking closely at images.

We invite papers that reconsider assessment in art history and architectural history at the university level. We welcome the results of classroom experiments and reflections, including but not limited to the alternative assessment methods mentioned above; new theoretical frameworks for teaching art history; experiments in student-centered approaches; historical perspectives on grading’s role in disciplining art historical knowledge; or collaborative redefinitions of assessment. Together, the panel asks: What is possible when our students approach art history not as a way to make the grade but as a tool to see the world anew?

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Note (added 18 August 2025) — The posting was updated to include the session on “Materiality and the Reception of Ancient Objects.”

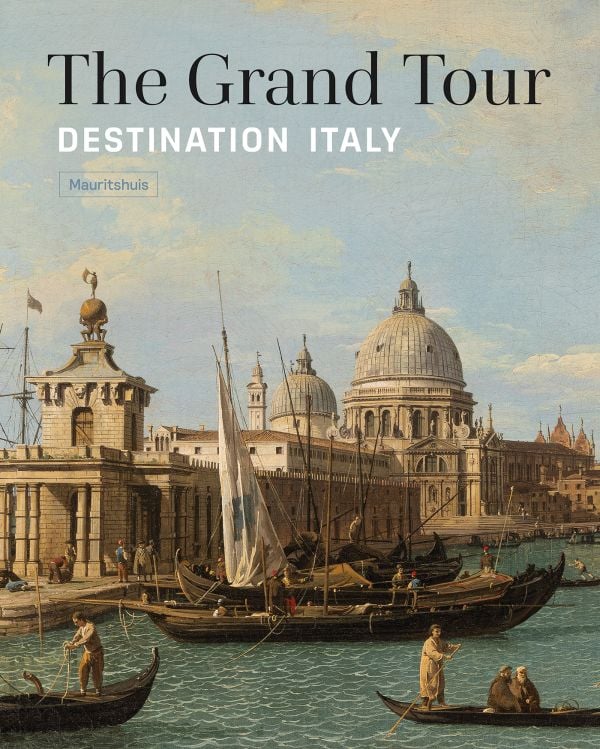

Exhibition | The Grand Tour: Destination Italy

Pompeo Batoni, Portrait of Thomas William Coke, 1774, installed at Holkham Hall.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release (3 July) for the exhibition:

The Grand Tour: Destination Italy

Mauritshuis, The Hague, 18 September 2025 — 4 January 2026

The Grand Tour: Destination Italy features masterpieces from three of the UK’s most esteemed stately homes: Burghley House, Holkham Hall, and Woburn Abbey. The art in this exhibition was collected on tours in the 17th and 18th centuries, when young British aristocrats finished their education by spending several years travelling in continental Europe. The highlights will include an impressive portrait of Thomas William Coke by Pompeo Batoni (Holkham Hall), work by Angelica Kauffman (Burghley House), and two grand Venetian cityscapes by Canaletto (Woburn Abbey), all of them on display in the Netherlands for the first time.

Burghley House: Great Collectors

Visitors will encounter two extraordinary travellers from the Cecil family: John Cecil, the 5th Earl of Exeter, and Brownlow Cecil, the 9th Earl. In the 17th century John and his wife made four tours of Europe, collecting pieces for their stately home, Burghley House. They purchased all kinds of things, including furniture and tapestries, but above all they purchased lots of paintings for their grand house. Their trips were far from easy. The couple travelled with their children, servants, and dozens of horses. Grand Tours were not without their challenges. Sick servants would have to be left behind, horses died in the heat, and carriages broke down.

Nathaniel Dance, Portrait of Angelica Kauffman, 1764 (Burghley House).

Angelica Kauffman: Beloved, Talented, and in Demand

In the 18th century their great grandson Brownlow left for Italy after the death of his wife. He had a particular favourite, Angelica Kauffman, a Swiss-Austrian painter who worked in Italy for many years and was the star of her age beloved, talented, and in demand. The exhibition will include a magnificent portrait of her by Nathaniel Dance that shows her looking straight at the viewer. For many, meeting Kauffman was the highlight of their Grand Tour. Vesuvius can be seen in the background of her portrait of Brownlow. No visit to Naples was complete without a climb to the top of this volcano, which was a popular destination in the 18th century—the earliest example of ‘disaster tourism’. Pietro Fabris painted a detailed image of the eruption of Vesuvius in 1767, with a crowd in the foreground watching the awesome power of nature.

Holkham Hall: Home of Art

Thomas Coke, the 1st Earl of Leicester, was just fifteen when he embarked on his six-year Grand Tour (1712–1718). He travelled with a clear goal in mind: to collect art for the future Holkham Hall, which he had built after his return, in Palladian style, with Roman columns, façades resembling temples and strict symmetry. His artworks were displayed to their best advantage in his palatial country home. During his travels, he collected paintings, drawings, sculptures, books, and manuscripts. Coke was regarded as one of the most important 18th-century collectors of the work of Claude Lorrain, the French master of Italian landscapes, including the fabulous View of a Seaport and Amphitheatre. The top item in the exhibition is an impressive portrait of his great nephew Thomas William Coke, painted by Pompeo Batoni, a typical Grand Tour portrait with a Roman statue from the Vatican in the background.

The cover of the catalogue includes a detail of Canaletto’s View of the Grand Canal in Venice, Looking West, with the Dogana di Mare and the Santa Maria della Salute, ca.1730–40 (Woburn Abbey).

Woburn Abbey: Obsession with Venice

The Grand Tour is synonymous not only with Rome, but also with Venice. John Russell, who became the 4th Duke of Bedford in 1735, visited the city on his Grand Tour (1730–31). Like many young aristocrats, he wanted a permanent memento to take home with him, and what could be more appropriate than a cityscape by Canaletto, the leading painter of 18th-century Venice? Eventually, John Russell commissioned an entire series comprising more than 24 paintings, the largest series of Canalettos still in existence. The paintings normally hang in the dining room at Woburn Abbey, the ancient family seat of the Russells.

The Grand Tour

These days many youngsters take a ‘gap year’ after high school, but a Grand Tour could easily last several years. Italy was the ultimate destination, with Rome, Florence, Naples, and Venice as the absolute highlights. En route, travellers would learn about art, architecture and culture, and collect artworks for their stately homes in England, just as we take back souvenirs nowadays. Yet these trips were not always innocent and high-minded. They are also known for their less salubrious distractions, including gambling and lustful pleasures. To keep the young men on the straight and narrow, they would be accompanied by chaperones. Such a ‘private tutor’ would mockingly be known as a ‘bear leader’. From the 18th century onwards, women also increasingly did the Grand Tour, sometimes with their entire family. The Napoleonic Wars (1803–15) brought the tradition of the Grand Tour to an end. In the 19th century, the advent of the steam train changed travel for good.

The catalogue is distributed by ACC Art Books:

Ariane van Suchtelen, The Grand Tour: Destination Italy (Waanders & de Kunst Publishers, 2025), 112 pages, ISBN: 978-9462626461, $45.

New Book | Travel Stories and the Eastern Adriatic

From The Institute of Art History at Zagreb:

Katrina O’Loughlin, Ana Šverko, and Elke Katharina Wittich, eds., Travel Stories and the Eastern Adriatic with a Section about the Travels of Thomas Graham Jackson (Zagreb: The Institute of Art History, 2025), 296 pages, ISBN: 978-9537875466, €20.

Travel Stories is the fourth collection of selected papers from a series of annual academic conferences held at the Institute of Art History – Cvito Fisković Centre in Split, which began in 2014. The current volume is a direct continuation of the book Discovering Dalmatia: Dalmatia in Travelogues, Images, and Photographs, published in 2019. The same editorial team and volume reviewers have this time grouped the selected papers from the Split conferences into two sections.

Travel Stories is the fourth collection of selected papers from a series of annual academic conferences held at the Institute of Art History – Cvito Fisković Centre in Split, which began in 2014. The current volume is a direct continuation of the book Discovering Dalmatia: Dalmatia in Travelogues, Images, and Photographs, published in 2019. The same editorial team and volume reviewers have this time grouped the selected papers from the Split conferences into two sections.

The first section, “Travellers and Travel Narratives,” brings together five papers related to travel narratives and the Eastern Adriatic over a broad timeline. These papers are authored by individuals from various backgrounds and discuss sources that include a variety of different media (lectures, drawings, books, photographs, diaries, letters), contributing to the exploration of the range of media used in travel narratives within this multimedia genre. The second section follows the Victorian architect Thomas Graham Jackson (1835–1924) on his journey along the eastern Adriatic coast, focusing on selected episodes from this trip, as described in his renowned three-volume work Dalmatia, the Quarnero, and Istria with Cettigne in Montenegro and the Island of Grado (Oxford, 1887), which is dedicated to the architectural and artistic heritage of this region.

The editorial process and publication of this book coincides with the first year of a new project funded by the Croatian Science Foundation, dedicated to Dalmatia and travel writing, ‘Where East Meets West’: Travel Narratives and the Fashioning of a Dalmatian Artistic Heritage in Modern Europe (c. 1675–1941), (Travelogues Dalmatia 2024–27).

c o n t e n t s

Acknowledgments

Ana Sverko — Preface: Exploring Genre, Place, and Travellers within the Travel Narrative

Section 1 | Travellers and Travel Narratives

• Frances Sands — Sir John Soane’s Lecture Drawings: A Virtual Grand Tour

• David McCallam — Carlo Bobba, Souvenirs d’un voyage en Dalmatie (1810): Travel, Empire, and Hospitality in the Early Nineteenth-Century Adriatic

• Ante Orlović — A Photographic Album with a Description of His Majesty the Emperor and King Franz Joseph I’s Tour through Dalmatia in 1875

• Boris Dundović and Eszter Baldavári — The Balkan Letters by Ernő Foerk: A Travelogue Mapping the Architectural Trajectories of Ottoman and Orthodox Heritage

• Dalibor Prančević and Barbara Vujanović — Ivan Meštrović’s Reflections from His Travels to the Middle East

Section 2 | Thomas Graham Jackson and the Eastern Adriatic

• Mateo Bratanić — Travellers, Historians, and Antiquaries: How Thomas Graham Jackson Wrote History in Dalmatia, the Quarnero, and Istria

• Krasanka Majer Jurišić and Petar Puhmajer — Thomas Graham Jackson and the Island of Rab

• Ana Torlak — Thomas Graham Jackson and Salona

• Sanja Žaja Vrbica — The Portrait of Dubrovnik by Thomas Graham Jackson

• Mateja Jerman — The Church Treasuries of Dalmatia and the Bay of Kotor through the Eyes of Thomas Graham Jackson

List of Illustrations

List of Contributors

Cover image: Soane office hand: Detail of a Royal Academy Lecture Drawing Showing an Interior View of the Temple of Jupiter at Diocletian’s Palace, Spalatro (Split), after Robert Adam, Ruins of the Palace of the Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia (London 1764, plate 33), 1806–19 (London: Sir John Soane’s Museum, SM 19/11/1; Ardon Bar-Hama).

Call for Articles | Fall 2026 Issue of J18: Archipelago

From the Call for Papers:

Journal18, Issue #22 (Fall 2026) — Archipelago

Issue edited by Demetra Vogiatzaki and Catherine Doucette

Proposals due by 1 September 2025; finished articles will be due by 1 February 2026

“Antillean art,” remarked St. Lucian poet Derek Walcott upon receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992, “is this restoration of our shattered histories, our shards of vocabulary, our archipelago becoming a synonym for pieces broken off from the original continent.” Walcott’s Nobel lecture, “The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory”, offers a compelling meditation on the interplay between art, history, and the archipelago as a space of fragmentation, multiplicity, and interconnectedness. In dialogue with Walcott’s reflections, Italian philosopher and politician Massimo Cacciari has framed the rise of early Cycladic culture in the Aegean Sea as the archetype of sociocultural relationality in Europe, inviting a reconsideration of the Archipelago as a model of geographical, as well as political negotiations.

As the eighteenth century witnessed the expansion of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the anchoring of European empires across Atlantic, African, Indian, and Mediterranean archipelagic complexes, the insights of Walcott and Cacciari challenge us to rethink how eighteenth-century art and architectural practices in archipelagic spaces were shaped by tensions between isolation, connection, empire, displacement, autonomy, and exchange. While offering an opportunity to reconsider the intertwined histories of colonialism, slavery, and territorialism, focusing on archipelagic structures can help “decenter” Western narratives. An archipelagic perspective is also critical to understanding how island societies navigated and negotiated their cultural identities and agency outside, or in spite of, colonial structures.

As the eighteenth century witnessed the expansion of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the anchoring of European empires across Atlantic, African, Indian, and Mediterranean archipelagic complexes, the insights of Walcott and Cacciari challenge us to rethink how eighteenth-century art and architectural practices in archipelagic spaces were shaped by tensions between isolation, connection, empire, displacement, autonomy, and exchange. While offering an opportunity to reconsider the intertwined histories of colonialism, slavery, and territorialism, focusing on archipelagic structures can help “decenter” Western narratives. An archipelagic perspective is also critical to understanding how island societies navigated and negotiated their cultural identities and agency outside, or in spite of, colonial structures.

This issue of Journal18 explores how archipelagic thinking informs the study of eighteenth-century art, architecture, and material culture. How might concepts of creolization, diaspora, and tidalectics, in the words of Kamau Brathwaite, reshape our understanding of artistic production and circulation? In the fragmentation of archival repositories, what can eighteenth-century objects and built environments made within archipelagic spaces reveal about the experiences of the people who lived there? How did eighteenth-century objects negotiate relationships between islands, oceans, and continents? How did artistic and architectural practices in the archipelago both reflect/reinforce and resist colonial power?

We encourage contributions that explore the metaphorical and material implications of the archipelago in artistic practices, cartography, and networks of exchange and use. We welcome interdisciplinary and innovative approaches to object study in the form of full-length articles or shorter pieces focused on single objects, interviews, or other formats.

To submit a proposal, send an abstract (250 words) and a brief biography to the following email addresses: editor@journal18.org, cd2bv@virginia.edu, and vogiatzaki@arch.ethz.ch. Articles should not exceed 6000 words (including footnotes) and will be due for submission by 1 February 2026. For further details on submission and Journal18 house style, see Information for Authors.

Issue Editors

Demetra Vogiatzaki, gta/ETH Zurich

Catherine Doucette, University of Virginia

Call for Papers | Character in Global Encounters with Architecture

This session is part of next year’s EAHN conference; the full Call for Papers is available here:

‘Character’ in Global Encounters with Architecture, 1700–1900

Session at the Conference of the European Architectural History Network, Aarhus, 17–21 June 2026

Chairs: Sigrid de Jong, Dominik Müller and Nikos Magouliotis

Proposals due by 19 September 2025

The eighteenth century was at once the period when Classical architecture was canonized in the Western world and beyond, and the moment when its supposedly universal ideal came into crisis. The study of competing practices and traditions of various medieval (Romanesque, Gothic, Byzantine) and vernacular architectures in Europe, and the allure of ‘Oriental’ styles (filtered through Turquerie and Chinoiserie) challenged the claims of Classicism, as did the encounters with different extra-European building traditions through travel and colonialism. These encounters prompted an avid preoccupation with cultural difference, as evidenced in Voltaire’s Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations (1756), Vico’s Principi di una scienza nuova d’intorno alla natura delle nazioni (1725–44), and Hume’s Of National Characters (1748).

Before the systematic global histories of architecture of the nineteenth century, and previous to the notion of style, Western authors employed a particular term to describe cultural specificity and difference: character. Stemming originally from the Greek word χαρακτήρ, its meaning evolved from the tool with which one carved signs on a wax or stone surface, over denoting these signs themselves, to the imprint these had on a reader or viewer. The distinctiveness of that impact, and the marks of identity of a whole culture in its environment and material culture, was encapsulated by its character. As such, from 1750 onwards the notion of character became ubiquitous in a variety of languages and was used in reference to people, buildings and landscapes, and shared across different genres of writing and scientific disciplines: from travel literature, political theory and ethnography, over treatises of art and architecture, to gardening manuals.

This session interrogates the architectural category of character in the globalizing world of the long eighteenth century, by zooming in on its meanings, implications, and complexities in moments of encounter between Western and non-Western cultures and architectures. We draw on recent inquiries into how Western travellers conceptualized non-Western architectures (Brouwer, Bressani, and Armstrong, Narrating the Globe, 2023), but also on works aiming to show how indigenous thinking conceptualized and criticized Western political and aesthetic norms (Graeber and Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything, 2021).

We are interested in instances of encounter addressing the following questions:

• How have Western accounts used the notion of character to describe non-Western architectures, building traditions, cultures, landscapes and places?

• How was the notion of character employed for architectures that challenged Western taxonomies and categorizations of architectural style?

• Which are the analogous notions in native languages that have been used to respond to encounters with Western architectures? How were these employed to process cultural specificity and otherness, and to describe, translate, acculturate or criticize Western cultural expressions (including mores and manners) from an indigenous perspective?

We welcome papers dealing with one or more of these questions in the period c. 1700–1900, across geographies. We are eager to discuss a variety of written, visual, and material sources, drawn from various disciplines, to expand the critical history of the term character beyond its well-established place in the history of European architectural theory.

Abstracts of no more than 300 words should be submitted by 19 September 2025 to sigrid.dejong@gta.arch.ethz.ch, nikolaos.magouliotis@gta.arch.ethz.ch, and mueller@arch.ethz.ch, along with the applicant’s name, email address, professional affiliation, address, telephone number, and a short curriculum vitae (maximum one page). Abstracts should define the subject and summarize the argument to be presented in the proposed paper. The content of that paper should be the product of well-documented original research that is primarily analytical and interpretative rather than descriptive in nature.

New Book | London: A History of 300 Years in 25 Buildings

Published last year by Yale UP, with a paperback edition due in September:

Paul Knox, London: A History of 300 Years in 25 Buildings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2024), 448 pages, ISBN: 978-0300269208, $35.

A lively new history of London told through twenty-five buildings, from iconic Georgian townhouses to the Shard

A walk along any London street takes you past a wealth of seemingly ordinary buildings: an Edwardian church, modernist postwar council housing, stuccoed Italianate terraces, a Bauhaus-inspired library. But these buildings are not just functional. They are evidence of London’s rich and diverse history and have shaped people’s experiences, identities, and relationships. Paul L. Knox traces the history of London from the Georgian era to the present day through twenty-five surviving buildings. He explores where people lived and worked, from grand Regency squares to Victorian workshops, and highlights the impact of migration, gentrification, and inequality. We see famous buildings, like Harrods and Abbey Road Studios, and everyday places like Rochelle Street School and Thamesmead. Each historical period has introduced new buildings, and old ones have been repurposed. As Knox shows, it is the living history of these buildings that makes up the vibrant, but exceptionally unequal, city of today.

Paul Knox is an expert in the social and architectural history of London. Originally from the UK, he is now University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech. He is the author of Metroburbia: The Anatomy of Greater London; London: Architecture, Building, and Social Change; and Cities and Design.

New Book | The London Club: Architecture, Interiors, Art

Coming September from ACC Art Books:

Andrew Jones, with photographs by Laura Hodgson, The London Club: Architecture, Interiors, Art (New York: ACC Art Books, 2025), 288 pages, ISBN: 978-1788843294, $75.

A stunning exploration of London’s most beautiful, interesting, and unusual members’ club architecture and interiors

A stunning exploration of London’s most beautiful, interesting, and unusual members’ club architecture and interiors

London has more private members’ clubs than any other city, with new locations opening every year. The UK capital has exclusive clubs for everyone from plutocrats and bishops to jockeys and spies. Written by Andrew Jones, travel writer for the Financial Times and author of The Buildings of Green Park, this large-format picture book is richly illustrated with newly commissioned photographs by Laura Hodgson, covering 300 years of the capital’s architecture and interior design. The London Club: Architecture, Interiors, Art offers a fascinating take on the structures and decorations inside some of the most niche spots in London, giving readers a one-off glimpse into the hidden corners of the city’s social infrastructure.

Andrew Jones has lived in the heart of London clubland, on the border of Mayfair and St James’s, for almost 20 years. He is the author of The Buildings of Green Park, a tour of certain buildings, monuments and other structures in Mayfair and St. James’s, and a contributor to Seeing Things: The Small Wonders of the World according to Writers, Artists, and Others. He writes about cities for the Financial Times, and has also written on architecture for Blueprint, Drawing Matter, and The London Gardener, as well as pieces on London for The World of Interiors and the Londonist.

leave a comment