Funding | Burlington Bursaries for Researching Drawings

From ArtHist.net:

The Burlington Magazine’s Travel Bursaries for Researching European Drawings

Applications due by 1 February 2026

We are delighted to announce a new initiative: The Burlington Magazine Travel Bursaries, generously funded by the Rick Mather David Scrase Foundation. These bursaries are designed to support emerging art historians undertaking research on old master drawings. The awards will fund travel to major collections worldwide to study works of Western art on paper from the Renaissance to 1900.

Typical awards will range from £2,000 to 2,500 for travel within Europe and £3,000–3,500 for intercontinental travel. Applications are welcomed from postgraduate and curatorial researchers worldwide. The deadline for applications is Sunday, 1 February 2026. Further details and application guidelines can be found at The Burlington website.

Call for Papers | Framing the Drawing / Drawing the Frame

From the Call for Papers as noted at ArtHist.net:

Framing the Drawing / Drawing the Frame

Bibliotheca Hertziana—Max Planck Institute for Art History, Rome, 13–15 May 2026

Organized by Tatjana Bartsch, Ariella Minden, and Johannes Röll

Proposals due by 16 January 2026

Leonardo da Vinci, Compositional Sketches for the Virgin Adoring the Christ Child, with and without the Infant St. John the Baptist, silverpoint, pen and brown ink, ca. 1480–85 (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.142.1). As Carmen Bambach notes in her entry for the drawing, “The geometric constructions at the lower right represent his attempts to work out the perspective within the composition, with respect to the spectator’s vantage point.”

The 2026 Gernsheim Study Days seek to explore the relationship between early modern drawings, frames, and framing.

In the early modern period, the frame as a physical object was something that could and, not infrequently, did cost more than the artwork it was framing. Together with the understanding of its economic value, the frame performed a monumentalizing role. The microarchitectural structure was used to signal the importance of an image through the imposition of new hierarchies of space. The symbolic dimension of the frame was both mobilized by artists as an integral part of compositional ensembles and retroactively applied to underscore the importance of certain images.

In the medium of drawing, with the physicality of the wrought object removed, the symbolic connotations associated with acts of framing came to be transposed to a two-dimensional plane, emphasizing the practice as a cultural technique. The form of elevation accomplished by the frame was transformed into a personal referencing system for the artist, part of a creative practice, where the addition of the drawn frame could transform a sheet of paper from an open field, a space for ideas to emerge, to a closed one, creating new hierarchies of space in the mise-en-page. Similarly, a drawn frame around a single motif on a sheet of paper with several motifs serves to illustrate the artist’s selection process and offers an opportunity for reflection on the connection between artist, viewer, and message to be conveyed. It is the goal of this conference to examine these semiotic potentials in and related to drawing in their multiplicity.

In addition to the generative role that forms of framing played in early modern drawings, we are interested in the framing of drawings themselves as it pertains to histories of collecting, reception, and museums. From Vasari’s Libro dei disegni to the modern passepartout, we seek to address how acts of framing shape or change our perception of drawings.

Finally, given the practical, economic, and symbolic significance of the frame, drawings for actual frames comprise an important line of inquiry in interrogating the relationship between drawing, frames, and framing. Alongside the use of the word cornice in Italian to refer to the frame in the early modern period, decorative surrounds were also identified in contemporary sources as ornamenti, a term that could refer both to the celebratory quality of frames as well as the nature of the frame as a liminal space or threshold where artists were able to reflect on the inventiveness of art making. In this context, papers might address the relationship between frame design and drawing and what impact—if any—the expanded drawing practices of the early modern period had on practices of framing.

We invite papers that treat frames and framing, broadly conceived, as they relate to drawing. Possible topics and questions that we hope to address include:

• Frame design and drawing for the decorative arts

• The role of frames and framing in the making or changing of meaning

• Inscriptions on drawings or, later, passepartouts, as a form of framing

• Marginalia as paratextual frames

• How the frame in drawing complicates our understanding of the frame

• The frame as mediator of drawings

• The frame as a metapictorial device

To submit a proposal, please upload a title, a 250-word abstract, and brief CV (no more than 2 pages) as a PDF document at https://recruitment.biblhertz.it/position/19759108 by 16 January 2026.

Conference languages are English, German, and Italian. The Bibliotheca Hertziana will organize and pay for accommodation and reimburse travel costs (economy class) in accordance with the provisions of the German Travel Expenses Act (Bundesreisekostengesetz).

Print Quarterly, December 2025

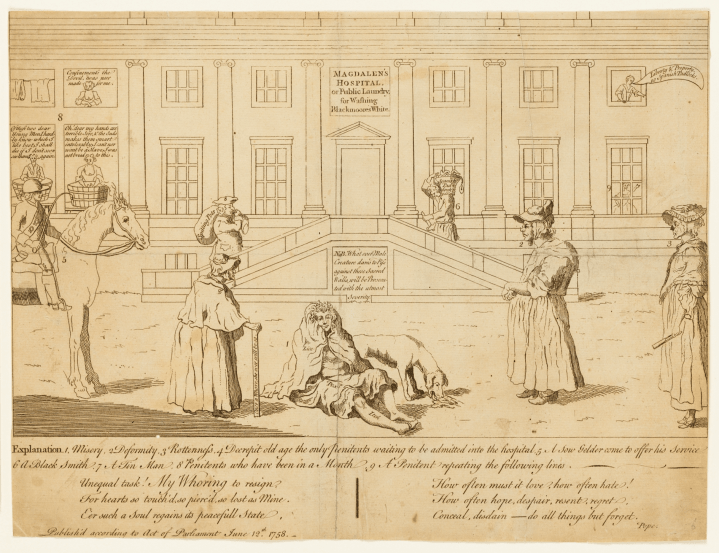

Anonymous artist, Magdalen’s Hospital, or Public Laundry for Washing Blackmoores White, 1758, etching, trimmed within the platemark, 232 × 307 mm (Oxford, Ashmolean Museum).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The long eighteenth century in the latest issue of Print Quarterly:

Print Quarterly 42.4 (December 2025)

a r t i c l e s

• Xanthe Brooke, “Spaignolet’s Drawing Book: An Album with Ribera Prints at Knowsley Hall,” pp. 379–89. This article focuses on an unpublished album containing 28 prints mainly by or after Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652). Brooke seeks to identify the sources and publishers of each impression, explores how the Earl of Derby used the album, and traces the growing taste for Ribera’s work among English collectors in the late seventeenth and the first decades of the eighteenth century.

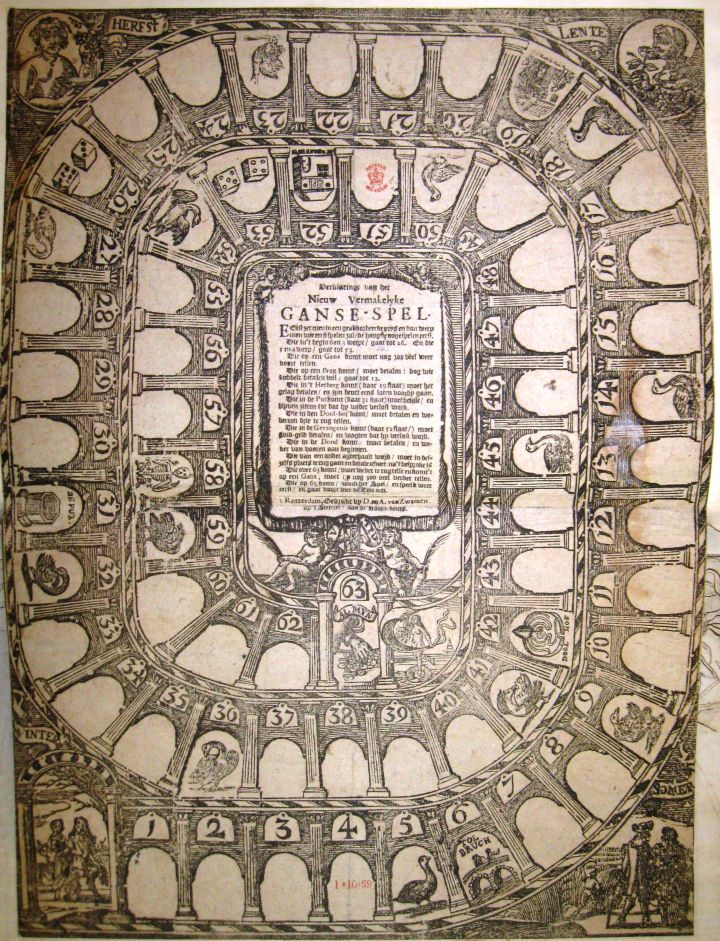

Anonymous artist, The New and Entertaining Game of the Goose, ca. 1759–87, woodcut, 470 × 360 mm (London: British Library, Creed Collection volume 8).

• Emma Boyd, “The Advent of the Magdalen Hospital: A Rare Satirical Print,” pp. 390–401. This article examines an anonymous etching in the Ashmolean Museum depicting the Magdalen Hospital, a charity for ‘penitent prostitutes’. The author discusses the print’s satirical commentary in relation to the charity’s controversial formation and the debates surrounding it. She also examines the print’s authorship within the context of other satirical prints and depictions of London street figures.

• Susan Sloman, “Gainsborough’s Cottage Belonging to Philip Thicknesse near Landguard Fort,” pp. 426–31. This short article contextualises an early etching by Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) from the 1750s, which the author proposes may have served as a subscription ticket for the engraving Landguard Fort, published in August 1754 by Thomas Major (1719–1799). The author also suggests that a painting by Gainsborough long assumed lost never existed.

• Felicity Myrone and Adrian Seville, “Two Unreported Games of the Goose in the Creed Collection in the British Library,” pp. 432–36. This short article describes two unknown examples of the Game of the Goose, one in printed form and the other in manuscript form. The provenance from the collection of London printseller Giles Creed (1798–1858), who specialized in ‘the history of ancient and modern inns, taverns, and coffee-houses’, is briefly traced.

n o t e s a n d r e v i e w s

Anonymous artist, published by Matthew and Mary Darly, Tight Lacing, or, Hold Fast Behind, 1 March 1777, etching and engraving, 351 × 247 mm (Farmington, CT: Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University).

• Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Review of Cristina Martinez and Cynthia Roman, Female Printmakers, Printsellers, and Print Publishers in the Eighteenth Century: The Imprint of Women, c. 1700–1830 (Cambridge University Press, 2024), pp. 445–47.

• Jean Michel Massing, Review of Anna Lafont, L’art et la race: L’Africain (tout) contre l’œil des Lumières (Les presses du réel, 2019), pp. 447–48.

• Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, Review of Elizabeth Gernerd, The Modern Venus: Dress, Underwear, and Accessories in the Late 18th-Century Atlantic World (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2024), pp. 448–49.

• Mathilde Semal, Review of Rolf Reichardt, Éventails symboliques de la Révolution. Sources iconographiques et relations intermédiales (Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2024), pp. 450–52.

• Robert Felfe, Review of Matthew Zucker and Pia Östlund, Capturing Nature: 150 Years of Nature Printing (Princeton Architectural Press, 2022), pp. 452–54.

• Sarah Thompson, Review of Timothy Clark, ed., Late Hokusai: Society, Thought, Technique, Legacy (British Museum, 2023), pp. 479–83.

Fellowships | The Reception of Antique Works of Art and Architecture

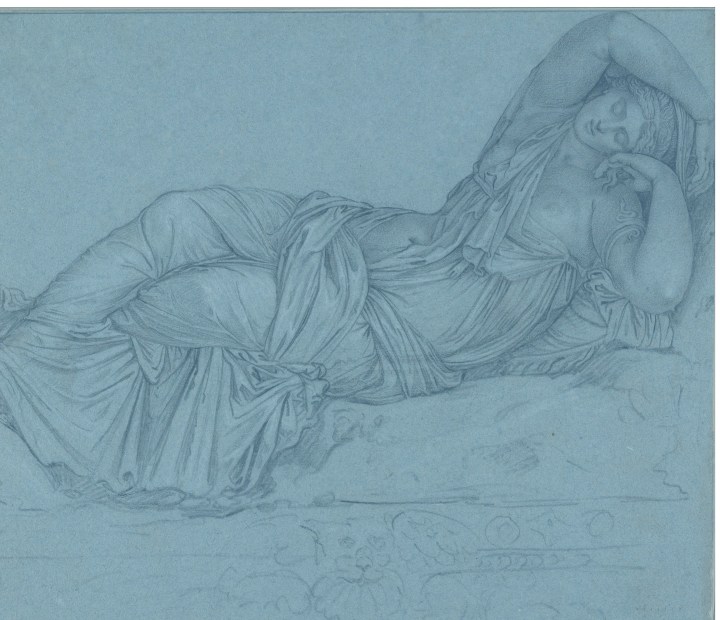

Hendrick Goltzius, Cleopatra/Ariadne, 1590–91, black and white chalk with pencil on blue paper, 25 × 30 cm

(Haarlem: Teylers Museum, purchased from the Odescalchi heirs in Rome, 1790, N061; CensusID 47461)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From ArtHist.net:

Census Fellowship in the Reception of Antiquity, 1350–1900

Humboldt-Universität (Berlin), Bibliotheca Hertziana (Rome), Warburg Institute (London), March–December 2026

Applications due by 31 January 2026

The Institut für Kunst- und Bildgeschichte, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, the Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max Planck Institute for Art History, and the Warburg Institute, School of Advanced Study, University of London, are pleased to announce a fellowship in Berlin, Rome, and London, offered at either the predoctoral or postdoctoral level. These fellowships grow out of the longstanding collaboration between the Humboldt, the Hertziana, and the Warburg in the research project Census of Antique Works of Art and Architecture Known in the Renaissance.

The fellowships extend the traditional chronological boundaries of the Census and are dedicated to research and intellectual exchange on topics related to the reception of antiquity in the visual arts from approximately 1350 to 1900. In the context of the fellowships, the topic of the reception of antiquity is also broadly conceived without geographical restriction. Proposals can optionally include a digital humanities perspective, engage with the database of the Census, or make use of the research materials of the Census project available in Berlin, Rome, and London.

The Humboldt, the Hertziana, and the Warburg sponsor a research grant of 6 months for students enrolled in a PhD program (predocs), or 4 months for candidates already in possession of a PhD (early career postdocs). Fellows can set their own schedule and choose how to divide their time evenly between at least two institutes, of which one must be the Hertziana. The stipend will be set at about 1,500 EUR per month at the predoctoral level and about 2,500 EUR per month at the postdoctoral level, plus a travel stipend of 500 EUR. The fellowship does not provide housing.

The sponsoring institutes adhere to the principles of diversity, equity, and inclusion, and therefore encourage applications from underrepresented groups. Candidates can apply via the portal available on the Hertziana website. They should upload the requested PDF documents in English, German, or Italian by 31 January 2026, with details of their proposed dates for the fellowship during the year 2026 (starting earliest March, ending latest December 2026).

Call for Papers | Undergraduate History Symposium, Istanbul

From the Call for Papers:

3rd Undergraduate Student Symposium

Department of History, Istanbul University, 5–6 May 2026

Proposals due by 29 March 2026

The 3rd Undergraduate Student Symposium organized by the Department of History at the Faculty of Letters, Istanbul University, will be held May 5–6, 2026 in the Kurul Odası. The symposium aims to support academic development at the undergraduate level by providing a platform for students from various universities to present their research on different periods and themes in history. Students wishing to present a paper should submit an abstract of 250–400 words via the online submission form by March 29. Presentations will be limited to 15 minutes. Accepted proposals will be announced on April 12. For inquiries, please contact edebiyat.kariyertarih@istanbul.edu.tr.

The 3rd Undergraduate Student Symposium organized by the Department of History at the Faculty of Letters, Istanbul University, will be held May 5–6, 2026 in the Kurul Odası. The symposium aims to support academic development at the undergraduate level by providing a platform for students from various universities to present their research on different periods and themes in history. Students wishing to present a paper should submit an abstract of 250–400 words via the online submission form by March 29. Presentations will be limited to 15 minutes. Accepted proposals will be announced on April 12. For inquiries, please contact edebiyat.kariyertarih@istanbul.edu.tr.

Call for Papers | Material Ecologies: Boston U. Graduate Symposium

From the Call for Papers:

Material Ecologies: Connecting Care, Nature, and Identity

The 42nd Annual Mary L. Cornille Boston University Graduate Symposium on the History of Art & Architecture

Boston University and MFA Boston, 10–11 April 2026

Coordinated by Allegra Davis and Jailei Maas

Proposals due by 1 February 2026 (extended from 15 January)

The graduate students of the Boston University History of Art & Architecture Department invite proposals for papers that explore themes of art and the environment, engaging questions of materiality, craft, and alternative ecologies, for the 42nd anniversary of the Mary L. Cornille (GRS ‘87) Boston University Graduate Symposium on the History of Art & Architecture.

In recent decades, as critical approaches to the environmental humanities have experienced rapid expansion, ecocritical art histories have examined aesthetic engagements with the natural world in light of extraction, pollution, and climate change, often reconsidering hierarchies imposed on the environment and artists’ relationships with natural subjects and materials. Ecofeminism, meanwhile, as both a social movement and a theoretical framework, has specifically linked human domination of nature with patriarchal structures, calling for the deconstruction of both gender and species-based divisions and oppressions. Taking cues from these movements, Material Ecologies will center materiality and feminist critique as lenses for environmental inquiry in art history, investigating how artists depict, consider, and collaborate with more-than-human beings to refigure humanity’s own relationships with the world around us. In this symposium, we aim to break down boundaries and hierarchies not only between humanity and nature, but also among academic and artistic disciplines, geopolitical borders, and material categories. How have artists used both traditional and innovative materials and methods to address themes of the environment, climate, and identity? Where do ecological, scientific, cultural, and artistic practices overlap and intersect, and what insights are produced as a result? What new ways of creating and being can we access by resisting the urge to insulate and taxonomize?

Possible subjects include but are by no means limited to: artistic collaborations with nature; the expanded field of sculpture; ecofeminism and decolonialism; queer and feminist craft practices; salvaged and repurposed materials; Black Feminist, Indigenous, and queer ecologies; and kinships between art and science.

Submissions should align with the goal of this symposium to center BIPOC, LGBTQIA2S+, feminist, and counter-colonial voices, fostering a space for these perspectives to resonate within the academy and beyond. We encourage interdisciplinary approaches, bringing together art history, architectural history, environmental humanities, cultural studies, literature, and more. We welcome submissions from graduate students at all stages and from any area of study in the global history of art and architecture. Papers must be original and unpublished. Please email as a single Word document: title, abstract (250 words or less), and CV to artsymp@bu.edu. The deadline for submissions is 15 January 2026. Selected speakers will be notified in early February. Presentations will be 15 minutes in length, followed by a question-and-answer session. The symposium will be held at the Boston University campus and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on April 10 and 11, 2026.

This event is generously sponsored by Mary L. Cornille (GRS ’87). For more information, please visit our website or email artsymp@bu.edu.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Note (added 18 January) — The posting was updated with the new, extended due date.

Exhibition | Landscapes by British Women Artists, 1760–1860

Opening soon at The Courtauld:

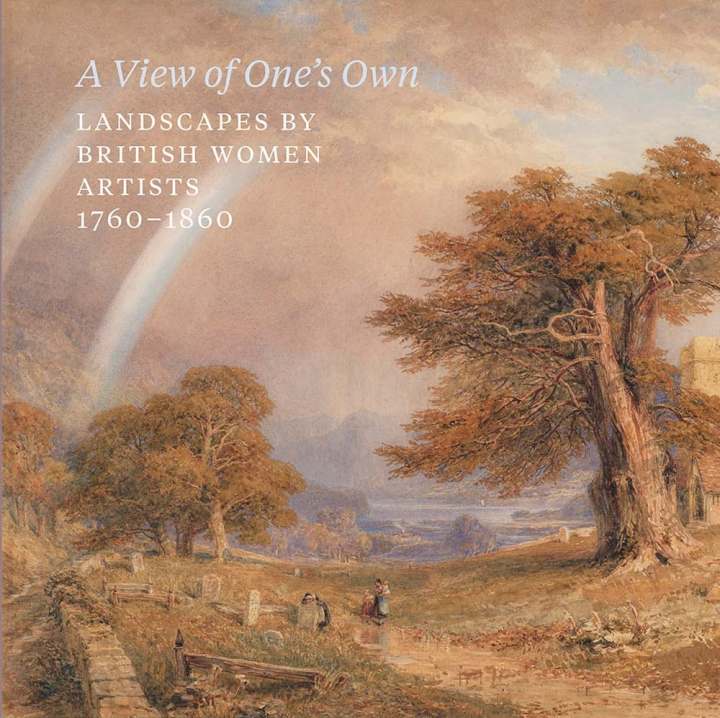

A View of One’s Own: Landscapes by British Women Artists, 1760–1860

The Courtauld Gallery, London, 28 January — 20 May 2026

Curated by Rachel Sloan

A View of One’s Own showcases landscape drawings and watercolours by British women artists working between 1760 and 1860 whose work represents a growing area of The Courtauld’s collection. These artists range from highly accomplished amateurs to those ambitious for more formal recognition. They have remained mostly unknown, and their works largely unpublished.

A View of One’s Own showcases landscape drawings and watercolours by British women artists working between 1760 and 1860 whose work represents a growing area of The Courtauld’s collection. These artists range from highly accomplished amateurs to those ambitious for more formal recognition. They have remained mostly unknown, and their works largely unpublished.

When the Royal Academy was founded in 1768, its members included two women; yet there would not be another female academician until Dame Laura Knight was elected in 1936. Despite this institutional exclusion, women artists in Britain continued to train, practice, and exhibit during this period, particularly in the field of landscape watercolours. This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue shed new light on these artists, working within a heavily male-dominated era in the arts. Some of the artists achieved recognition during their lifetimes while others’ work remained private. The ten artists featured include Harriet Lister and Lady Mary Lowther, who were among the first to depict the Lake District; Amelia Long, Lady Farnborough, one of the first British artists to travel to France following the Napoleonic Wars; and Elizabeth Batty, whose works appearing in the show were rediscovered only a few years ago.

Artists: Harriet Lister, Mary Lowther, Mary Mitford, Elizabeth Susan Percy, Mary Smirke, Eliza Gore; Fanny Blake, Amelia Long, Elizabeth Batty, and Richenda Gurney.

Rachel Sloan, ed., A View of One’s Own: Landscapes by British Women Artists, 1760–1860 (London: Paul Holberton Publishing, 2026), 72 pages, ISBN: 978-1913645977, £20. With contributions by Susan Owens, Rachel Sloan, and Paris Spies-Gans.

Rachel Sloan is Associate Curator for Works on Paper at The Courtauld Gallery. Paris A. Spies-Gans is a historian and art historian, with a focus on gender and culture in Britain and France during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries; she is currently a Junior Fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Susan Owens, formerly Curator of Paintings at the V&A, is an independent scholar; she has published widely on 19th-century British art and culture and has a particular interest in drawing and landscape.

Exhibition | The Barber in London

Now on view at The Courtauld:

The Barber in London: Highlights from a Remarkable Collection

The Courtauld Gallery, London, 23 May 2025 — 28 Jun 2026

Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Portrait of Countess Golovine, ca. 1800, oil on canvas, 84 × 67 cm (The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, 80.1).

A selection of exceptional paintings from the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, is on view at The Courtauld Gallery for an extended display from May 2025, while the Barber undergoes a major refurbishment project. The Barber Institute of Fine Arts was founded as a university gallery in 1932, the same year as The Courtauld Institute of Art and its collection. Both were intended to encourage the study and public appreciation of art. Today, the Barber and The Courtauld Gallery are home to two of the finest collections of European art in the country.

Highlights from the collection at the Barber include important works such as Frans Hals’s Portrait of a Man Holding a Skull (c. 1610–14), Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s Portrait of Countess Golovina (1797–1800), Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s The Blue Bower (1865), and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Woman in a Garden (1890). In addition, a handful of paintings with strong links to The Courtauld’s own collection will be embedded in the permanent collection displays, among them Joshua Reynolds’s monumental double portrait Maria Marow Gideon and Her Brother William (1786–87).

The Prado Acquires Its First Sculpture by Luisa Roldán

Luisa Roldán, The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, 1691, polychrome terracotta and wood

(Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release (18 December 2025) . . .

The Museo del Prado has taken an important step in reshaping the story of Spanish Baroque art with the acquisition of The Rest on the Flight into Egypt by Luisa Roldán, known as La Roldana. Signed and dated 1691, the sculpture marks the first time one of Roldán’s works enters the Prado’s collection—despite her name having long appeared on the museum’s façade alongside Spain’s great masters.

Luisa Roldán (1652–1706) was a remarkable figure in her time: the first woman to be appointed sculptor to the Spanish court, serving under both Charles II and Philip V. Yet, like many women artists of her era, her work has remained underrepresented in major museum collections. This newly acquired sculpture helps to correct that absence and brings her artistry into direct dialogue with the Prado’s holdings of Baroque painting and sculpture.

The work, made of polychrome terracotta and wood, depicts the Holy Family pausing to rest during their flight into Egypt. At first glance, the scene feels intimate and serene, but a closer look reveals Roldán’s extraordinary technical skill. The modeling is delicate and expressive, the gestures natural and carefully observed. The polychromy—exceptionally well preserved—adds warmth and immediacy, while details such as the tree framing the composition give the scene a quiet narrative depth.

The sculpture comes from the renowned Güell collection, long considered a reference point for Spanish sculpture, and was recently acquired at an Abalarte auction for €275,000. Purchased by Spain’s Ministry of Culture and assigned to the Prado, the piece now joins a collection that includes major devotional works by artists such as Gregorio Fernández, Pedro de Mena, Juan de Mesa, and Luis Salvador Carmona. Its arrival strengthens the Prado’s exploration of the relationship between sculpture and painting in Baroque Spain; Roldán’s work resonates with contemporaries such as Luca Giordano, whose paintings are already represented in the museum, highlighting shared interests in movement, emotion, and theatricality across artistic media.

Beyond its artistic importance, the acquisition carries symbolic weight. By welcoming Roldán’s sculpture into its galleries, the Museo del Prado publicly acknowledges the central role women artists played in shaping Spain’s artistic heritage. It is not simply a matter of adding one work to the collection, but of expanding the narrative of art history to better reflect its true complexity. With The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, Luisa Roldan finally takes her place inside the Prado—not just in name, but in substance—offering visitors a fuller, richer view of the Spanish Baroque and the artists who defined it.

Notre Dame’s Raclin Murphy Museum of Art Announces New Gift

From the press release (8 December 2025) . . .

Virgin Immaculata, 1730–33, Meissen Porcelain Manufactory, hard-paste porcelain, 8 inches high (South Bend: Raclin Murphy Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame, Virginia A. Marten Endowment for Decorative Art 2022.014).

The Raclin Murphy Museum of Art at the University of Notre Dame announces a major gift from the Marten Charitable Foundation through the stewardship of Gini Marten Hupfer, Foundation leader and member of the Museum’s Advisory Council. The tandem naming and endowment gift was inspired by the legacy of Virginia Marten (1925–2022), a long-standing, former member of the Advisory Council and devoted Museum supporter.

The gift will confer the name ‘Marten Family Gallery’ on the current east gallery of European Art before 1700. Works by Vicenzo Spisanelli, Claude Lorrain, Giuseppe Ribera, and Bartolomeo Veneto, among others, are featured in the gallery. With naming the gallery, a permanent feature, centered in the gallery, will be installed; to be called the ‘Marian Court’, it will be a permanent display featuring Marian imagery from the Raclin Murphy’s extensive holdings to honor Virginia Marten’s particular devotion to Mary, the Mother of Christ, and her love of art. Currently, images based on Marian iconography, ranging from paintings by Francesco Francia to Hans Memling to Giorgio Vasari, are highlighted in this space.

Complementing the named gallery, the second part of the gift establishes the Marten Family Endowment for Marian Art. The new endowment will provide support for research, conservation, acquisitions, interpretation, and programming to advance scholarship and appreciation of the traditions of Marian Art. A unique endowment to the institution, it underscores both the Museum’s and the University’s commitment to research and inquiry.

“This gift is meant to honor my sweet mother, Virginia Marten’s love for both Notre Dame, the Blessed Mother, and her passion for the arts. We believe we found the perfect space in which to do just that at the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art. I know my mother would be thrilled and humbled by this,” states Gini Marten Hupfer.

“The support of the Marten Family, beginning with Virginia and steadfastly followed by her children, is truly remarkable and inspiring,” states Joseph Antenucci Becherer, Director and Curator of Sculpture. “The Raclin Murphy Museum of Art and the University of Notre Dame are uniquely positioned to facilitate and celebrate the study and appreciation of Marian imagery, thus truly honoring the legacy of Virginia and her family. Their gift and endowment mark an exceptional moment when love, devotion, and scholarship converge.”

leave a comment