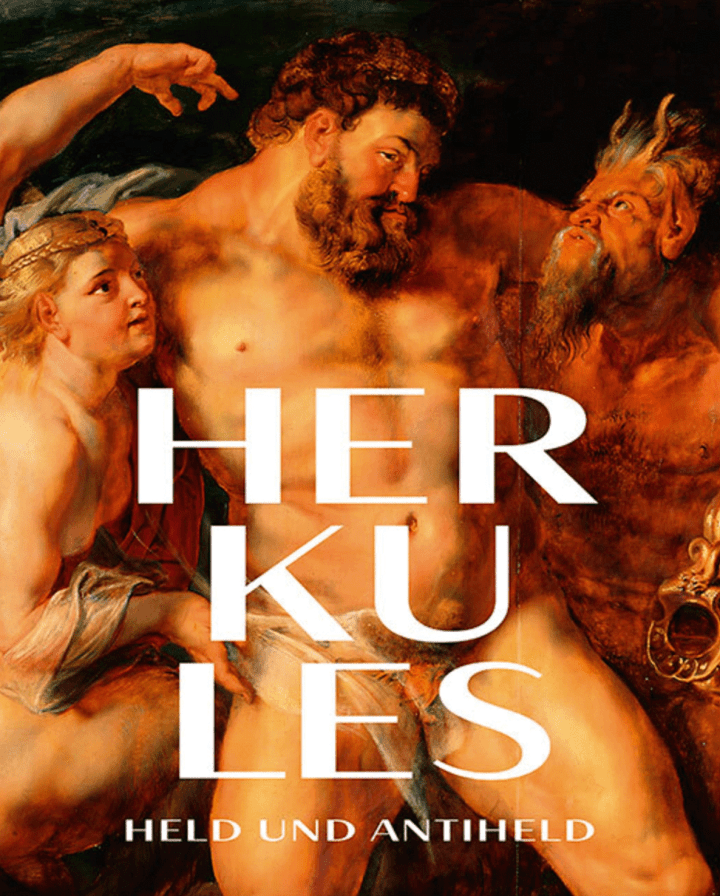

Exhibition | Hercules: Hero and Anti-Hero

Exhibition photo with a mid-19th-century plaster cast after Balthasar Permoser’s ‘Saxon Hercules’. As noted on the SKD’s Instagram account, “The original crowned the Wall Pavilion of the Dresden Zwinger from 1718 to 1945, symbolising its patron, Augustus the Strong, with his astonishing physical strength and the Herculean efforts he undertook every day as the Saxon-Polish ruler. Where Hercules dwells with the vault of heaven, the Garden of the Hesperides cannot be far away. And so Permoser’s Hercules gazed upon the orange trees in the Zwinger courtyard, which bore the apples of the Hesperides, as it were, and promised Saxony a golden age.”

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release for the exhibition:

Hercules: Hero and Anti-Hero

Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Zwinger, Dresden, 22 November 2025 — 28 June 2026

Hercules (‘Heracles’ in Greek), the best-known hero of classical antiquity, is one of the most enduring and popular mythical figures anywhere in the world. His name is universally known, and the phrase ‘a Herculean task’ is an everyday expression for anything requiring extraordinary strength and effort.

The Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections, SKD) is dedicating an exhibition to this demigod in the Winckelmann Forum of the Semper Gallery of the Zwinger. With Hercules: Hero and Anti-Hero, the Skulpturensammlung bis 1800 (Sculpture Collection up to 1800) and the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery) present a wide range of depictions of this mythological character. Featuring 135 objects, including top-quality sculptures, paintings, prints, coins, armour, and works of the goldsmith’s art, the exhibition explores the question of why Hercules has been such a fascinating figure for millennia and continues to be so today—one need only think, for example, of some of the major films of recent years.

As the son of the supreme deity Zeus and the Theban queen Alcmene, Hercules was a demigod—with superhuman strength and human flaws. His popularity was revived during the Renaissance. In Rome, dozens of large-scale Hercules statues were already known in the sixteenth century, and these had a huge influence on early modern art. The exhibition showcases works of art from classical antiquity to the neoclassical period, with some glimpses into the present day. Alongside objects from the rich holdings of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, there are prestigious loans from such eminent institutions as the Vatican Museums in Rome, the Prado in Madrid, the Louvre in Paris, and the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen.

As the son of the supreme deity Zeus and the Theban queen Alcmene, Hercules was a demigod—with superhuman strength and human flaws. His popularity was revived during the Renaissance. In Rome, dozens of large-scale Hercules statues were already known in the sixteenth century, and these had a huge influence on early modern art. The exhibition showcases works of art from classical antiquity to the neoclassical period, with some glimpses into the present day. Alongside objects from the rich holdings of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, there are prestigious loans from such eminent institutions as the Vatican Museums in Rome, the Prado in Madrid, the Louvre in Paris, and the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen.

In a prologue and five chapters, the exhibition explores the famous ‘Labours of Hercules’, his relationships with women, his anti-heroic escapades, and his role as a model of virtue for rulers such as Alexander the Great and August the Strong. Balthasar Permoser’s colossal Saxon Hercules, created for the Rampart Pavilion of the Dresden Zwinger, bears witness to this.

Hercules was evidently not only strong and virtuous. In some situations, he behaved dishonourably, succumbed to vice, or committed cruel injustices, even against his own children. He often fought against evil for the good of humanity, but he was also a murderer, rapist, drunkard, and thief. Through significant works of art and an extensive accompanying programme, the exhibition encourages reflection on the role of heroism in history and its relevance in our society today. Particular attention is paid to the extraordinary narrative richness of the myth.

Videos telling eight of the stories about Hercules have been created specially for the exhibition. Dresden-born actor Martin Brambach—known for his role as Chief Inspector Peter Michael Schnabel in the television series Tatort—relates important and amusing episodes from the life of the hero and anti-hero. A multimedia guide is available free of charge.

Holger Jacob-Friesen, ed., Herkules: Held und Antiheld (Dresden: Sandstein Kultur, 2025), 200 pages, ISBN: 978-3954988945, €38.

leave a comment