Exhibition | Dealing in Splendour

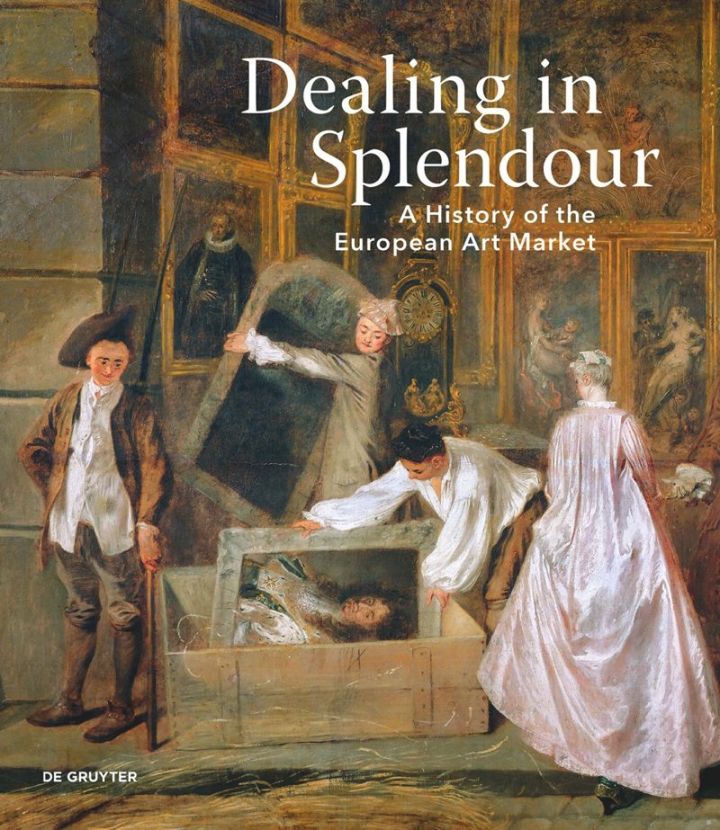

Willem van Haecht, The Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest, 1628, oil on panel

(Antwerp, Rubenshuis, City of Antwerp Collection, Rubenshuis)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Now on view in Vienna at the Liechtenstein Garden Palace:

Dealing in Splendour: A History of the European Art Market

Noble Begierden: Eine Geschichte des Europäischen Kunstmarkts

Gartenpalais Liechtenstein, Wien, 30 January — 6 April 2026

Curated by Stephan Koja, Christian Huemer, and Yvonne Wagner

With a history reaching back over four centuries, the Collections of the Princely Family of Liechtenstein are part of a long tradition of collecting that spans many generations. Essential to this at all times has been a policy of active collecting. In the past as in the present, new acquisitions shaped the appearance of the galleries. The art collection has thus been formed not only by the personal tastes of the various princes but also by the art market with its changing sales strategies, trend-setting individuals, and economic factors.

Against this background, Dealing in Splendor addresses the fascinating history of the European art market. Spotlights will be shone on structures, centres of innovation, influential personalities, and marketing methods from antiquity to the nineteenth century, revealing that many of these methods have changed very little up to the present day. Auctions were held in ancient imperial Rome. In Antwerp, art trade fairs were already attracting an international clientele in the sixteenth century, and the first catalogues raisonnés of Old Masters were compiled by art dealers in the eighteenth century.

Against this background, Dealing in Splendor addresses the fascinating history of the European art market. Spotlights will be shone on structures, centres of innovation, influential personalities, and marketing methods from antiquity to the nineteenth century, revealing that many of these methods have changed very little up to the present day. Auctions were held in ancient imperial Rome. In Antwerp, art trade fairs were already attracting an international clientele in the sixteenth century, and the first catalogues raisonnés of Old Masters were compiled by art dealers in the eighteenth century.

These and other enthralling insights into the history of the European art market await you at the Liechtenstein Garden Palace in Vienna, with major works from the Princely Collections appearing alongside sensational loans in the largest annual temporary exhibition we have mounted to date. The extensive catalogue will boast essays by leading experts in the field of art market scholarship, bringing interdisciplinary approaches to bear in a volume that will provide a comprehensive overview of the subject.

Art as a Commodity: The Flourishing Art Market of Antiquity

Even in ancient Roman times, there was a flourishing art market, sustained by a network of collectors, connoisseurs, buyers, and agents. Early forms of serial production and market adjustment were already developed and continued to have an effect into the early modern age. The great demand for classical Greek works led to a burgeoning production of replicas, variations, and reduced-size copies, which Roman collectors acquired specifically for particular rooms and functions. Workshops all over the Mediterranean specialized in reproducing famous representational formulas in order to provide objects in various price ranges—from monumental copies in marble to small bronze statuettes.

International Trade: Forchondt

Prince Karl Eusebius I von Liechtenstein had a particularly long and intensive connection with the Forchondt family of dealers. They had an international presence with branches in Antwerp, Vienna, and the Iberian Peninsula, shipping works of art and furniture in all price categories to destinations as far afield as South America. Karl Eusebius’s son, Prince Johann Adam Andreas I, was likewise a client of the Forchondts, from whom he purchased many of his most important acquisitions, including paintings by Rubens and van Dyck. This business relationship with the Forchondts, holders of an imperial privilege as jewellers to the imperial court, lasted until the reign of Prince Joseph Wenzel I.

Serial Production in the Fifteenth Century

In the Italian city-states of the fifteenth century, the emergent ruling families, foremost among them the Medici in Florence, made systematic use of art patronage. By erecting imposing monuments, they shaped the appearance of the cities and demonstrated their power. They commissioned chapels and altarpieces, and alongside the Church were the most prominent and important patrons of the era. However, there were also classes of customers with smaller purses. The prices for works of art depended on the materials used, the time and labour involved, and the prestige of the masters who had made them. The workshops produced particularly popular motifs in various price ranges, some being offered for sale as ready-made works, without having been previously commissioned. Outlay and labour were reduced by turning out multiple copies of a work with just minor variations, or by serial production in suitable materials such as terracotta.

The Brueg(h)el Dynasty

Pieter Bruegel the Elder was one of the most important Flemish painters of his time. His compositions were so successful that copies of his works were made in his workshop and in those of his descendants. A whole dynasty of painters and numerous imitators drew on his works even after his death, continuing to sell them, often with only minimal changes, at a healthy profit.

The Beginnings of Large-scale Production in the Low Countries

One notable feature of Holland’s seventeenth-century Golden Age was the unusual wealth of art works, particularly paintings, in the homes of its burghers. In order to keep up with demand artists developed methods that shortened their working hours and increased their productivity. To achieve this, they specialized in particular genres, one such practitioner being Jan van Goyen, whose reduced palette both limited his material expenses and became his hallmark. His landscapes earned him international acclaim. Jan Davidsz. de Heem was famous for his opulent still lifes. Rachel Ruysch made a successful speciality of the flower still life.

Souvenirs from the Grand Tour

Baccio Cappelli and Girolamo Ticciati, Galleria dei Lavori, Badminton Cabinet, 1720–32 (Collection of the Princely Family of Liechtenstein, acquired in 2004 by Prince Hans-Adam II von und zu Liechtenstein).

In the seventeenth and eighteenth century, journeys taking in the centres of European culture were an important part of the education of scions of the nobility. In British society in particular, the so-called Grand Tour was regarded as the height of fashion, with the result that in the countries visited, in particular Italy with Rome as its cultural centre, a veritable industry grew up to cater for these young tourists, with accommodation, cicerones, and guidebooks to the sights—and souvenirs of the sights to take back home. The most popular of these were the views known as capricci—compositions of various statues, ruins, and edifices that in reality stood nowhere near one another. In Rome, the most successful artists in this field were Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Giovanni Paolo Pannini. It was regarded as especially prestigious to have one’s likeness painted by a well-known portraitist, or best of all by Pompeo Girolamo Batoni. The phenomenon of the souvenir was possibly carried to its greatest extreme by Henry Somerset, third duke of Beaufort, who commissioned the monumental Badminton Cabinet from the grand-ducal Galleria dei Lavori in Florence.

From Dilettante to Connoisseur: Edme-François Gersaint

During the eighteenth century, Paris and London became centres of innovation in the art market. There the auction scene was given fresh impetus with the arrival of influential experts and auctioneers, elegant auction rooms, printed sale catalogues, and exhibitions that became veritable social spectacles. A pioneering role in these developments was played by Edme-François Gersaint, who blazed new trails with his shop on the Pont Notre Dame, his auctions, and his detailed auction catalogues.

Art Historians, Expertise, and the Establishment of Canons of Works

Attributions and provenances—which had assumed increasing importance over the previous century—now lay in the hands of scholars, whose opinions as proclaimed in catalogues raisonnés influenced contemporary tastes and above all the price of works included in these publications. The value of the works increased or decreased depending on their purported authenticity (or lack of it). In many cases the criteria for authenticity were necessarily limited to stylistic characteristics. These were duly contested, in scholarly circles and elsewhere. This can be seen particularly clearly in the case of Rembrandt, whose body of works expanded or contracted depending on the scholar surveying his oeuvre.

Art for the Masses: The Revolutionary Art Market of the Nineteenth Century

In the nineteenth century the art market was revolutionized. New forms of presentation and serial production and the reproduction of images in huge numbers made art into a mass medium that circulated all over the world. Firms such as Goupil et Cie professionalized these mechanisms by systematically providing reproductions of famous works of art for various categories of buyer. At the same time dealers such as Charles Sedelmeyer established the phenomenon of the art spectacle, which—accompanied by deliberately dramatic presentation, advertising, and skilful use of media—attracted huge crowds. Thus, in the nineteenth century various innovative strategies directed at a wide sector of the public came together to shape the art market of the time, forming the basis for the present-day art business.

Curators

Stephan Koja, Director of the Princely Collections of Liechtenstein

Christian Huemer, Head of the Belvedere Research Center

Yvonne Wagner, Chief Curator of the Princely Collections of Liechtenstein

Christian Huemer and Stephan Koja, eds., Dealing in Splendour: A History of the European Art Market (Berlin: De Gruyter Brill, 2026), 448 pages, ISBN: 978-3689241063 (German) / ISBN: 978-3689241070 (English), €59 / $65.

leave a comment