Call for Papers | On the Use and Abuse of Antiquity in 18th-C. Life

From the Call for Papers:

On the Use and Abuse of Antiquity in 18th-Century Life: Classical References and Their Subversion in the Age of Enlightenment

University of Chicago John W. Boyer Center in Paris, 22–23 May 2025

Proposals due by 15 December 2024

Ingres, The Apotheosis of Homer, 1827, oil on canvas, 386 cm × 512 cm (Paris: Musée du Louvre).

It is a well-established fact, frequently analysed by literary critics, that Greek and Roman Antiquity lies at the heart of 18th-century culture. The significance attributed to ancient authors in 18th-century collèges is often acknowledged, but references to classical figures in fact permeate all forms of the literary and visual arts, whether in the light-hearted forms of Baroque and Rococo or the austere severity of Neoclassicism. Scholars have often highlighted the idealisation of ancient socio-political models, which served as counterpoints to contemporary reflections and critiques, extending from the writings of philosophers to the proclamations and imagination of Revolutionary thinkers. The classical world was imbued with an exemplary value, conceived as an alternative framework through which to contemplate and categorise a frequently problematic present, or to advocate for political, social, and aesthetic reforms. Antiquity offered ideas and images that constituted a kind of second language through which the world of the Enlightenment could be reimagined.

However, any process of re-functionalisation and re-valorisation is inevitably accompanied by subversions, instrumentalization, and alterations. For a reference to be productive and applicable to a new and changing context, it must undergo modification that renders it relevant and exploitable, allowing it to bear meanings beyond the scope of its original formulation. In all cultural domains, ancient texts were either faithfully reproduced, critically commented upon, or openly reinterpreted according to the argumentative needs of writers, who, whether intentionally or not, projected their worldview and concerns onto these works. Precisely because Antiquity functioned as a ‘second language’, its words could only serve as instruments for the description and analysis of reality to the extent that they lost their original meaning and took on new ‘semantic’ valences, enabling them to convey content more attuned to the concerns of the time.

This colloquium aims to analyse and explore these deviations, shedding light on the highly productive dialectical play that takes place between an increasingly historicist and proto-scientific reception of the ancient world (with the emergence of disciplines such as archaeology, philology, etc.) and the still very free and fertile use of classical heritage, which was often employed with little constraint to support any and all ethical, political, or aesthetic arguments. Our goal is to identify the misunderstandings or ‘subverted’ reuses of classical texts, histories, and figures. Whether these fluctuations occur in the literal but reoriented reproduction of phrases, maxims, or passages from ancient texts, or more broadly in the reception of classical models in which new symbolic potentialities are detected, we wish to delve deeper into the qualities and purposes of these transformations of ancient material, analysing their pathways and dead ends, their distortions and their reconfigurations.

Why refer to Antiquity, and with what specific objectives or purposes? How were maxims, historical or philosophical texts, and the pantheon of ancient heroes and gods reinterpreted in the Age of Enlightenment, and how were they integrated into the contemporary cultural discourse? What demands for fidelity, and what modernising distortions were imposed upon Greek and Roman treatises and literature? How did any reappropriation of ancient discourse and its imagery ultimately prove suitable for the new expressive and ideological needs of the philosophes, and how could these same images also lead to their condemnation?

Presentations, in French or English, must not exceed 30 minutes. The conference organizers will cover travel and accommodation expenses for all invited speakers. A publication of the conference proceedings is planned.

Proposals for papers, in French or English, consisting of 250–300 words, accompanied by a brief bio-bibliography including institutional affiliations, should be submitted by 15 December 2024, to glenn.roe@sorbonne-universite.fr and dario.nicolosi.92@gmail.com. Acceptance decisions will be communicated to the authors by 15 January 2025.

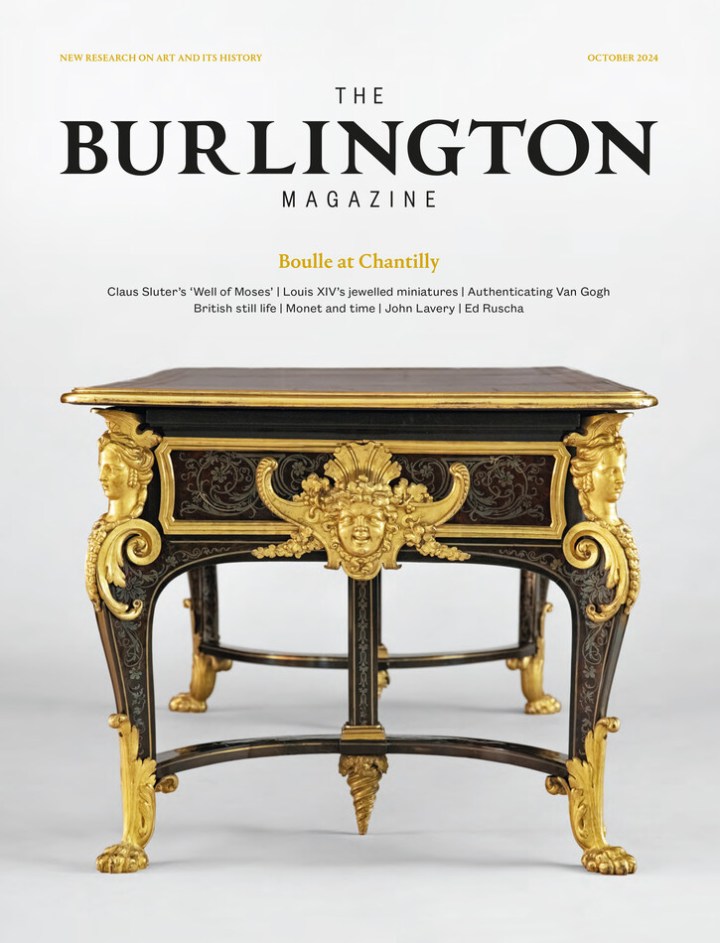

The Burlington Magazine, October 2024

The long 18th century in the October issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 166 (October 2024)

e d i t o r i a l

e d i t o r i a l

• “Restoring the ‘belle époque’,” pp. 995–96.

The Musee Jacquemart-André is a treasure house that graces the Haussmann boulevards in Paris and is perhaps not nearly as well-known as it should be. The recent re-opening of the museum on 6th September, following a period of closure for conservation, therefore provides a welcome opportunity to draw fresh attention to this most romantic and beguiling of collections and the elegant building that houses it.

a r t i c l e s

• Jacob Willer, “Annibale Carracci and the Forgotten Magdalene,” pp. 1028–35.

A painting the collection of the National Trust at Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire, is published here as a work of Annibale Carracci’s maturity. Related to comparable compositions which derive from it, in collections in Rome and Cambridge, it was acquired in Florence in 1758 for the 1st Baron Scarsdale.

• Samantha Happé, “Portable Diplomacy: Louis XIV’s ‘boîtes à portrait’,” pp. 1036–43.

Louix XIV’s ambitious and carefully orchestrated diplomatic programme included gifts of jewelled miniature portraits known as ‘boîtes à portrait’. Using the ‘Présents du Roi’, the circumstances around the commissioning and creation of these precious objects can be explored and a possible recipient suggested for a well-preserved example now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

r e v i e w s

• Alexander Collins, Review of the exhibition André Charles Boulle (Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly, 2024), pp. 1056–59.

• Claudia Tobin, Review of the exhibition The Shape of Things: Still Life in Britain (Pallant House Gallery, 2024), pp. 1067–69.

Helen Hillyard, Review of of the recently renovated galleries of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, pp. 1077–79.

• Colin Thom, Review of Steven Brindle, Architecture in Britain and Ireland, 1530–1830 (Paul Mellon Centre, 2024), pp. 1080–81.

• Christopher Baker, Review of Bruce Boucher, John Soane’s Cabinet of Curiosities: Reflections on an Architect and His Collection (Yale University Press, 2024), pp. 1087–88.

o b i t u a r y

• Christopher Rowell, Obituary for Alastair David Laing (1944–2024), pp. 1094–96.

Although renowned in particular for his expertise on the art of François Boucher, Alastair Laing had very wide-ranging art historical taste and knowledge, which he shared with great generosity of spirit. He curated some important exhibitions and brought scholarly rigour to his inspired custodianship of the art collections of the National Trust.

leave a comment