Exhibition | Picturing Nature: British Landscapes

John Robert Cozens, View of Vietri and Raito, Italy, ca. 1783, watercolor over graphite on cream laid paper (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Stuart Collection, museum purchase funded by Francita Stuart Koelsch Ulmer in honor of Dena M. Woodall).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Now on view at the MFAH:

Picturing Nature: The Stuart Collection

of 18th- and 19th-Century British Landscapes and Beyond

The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, 12 January — 6 July 2025

Featuring more than 70 works of art in a variety of media, Picturing Nature: The Stuart Collection of 18th- and 19th-Century British Landscapes and Beyond explores how the genre of landscape evolved during an era of immense transformation in Britain. This diverse collection of watercolors, drawings, prints, and oil sketches traces the shift from topographical and picturesque depictions of the natural world to intensely personal ones that align with Romantic poetry of the period. The exhibition spotlights the Stuart Collection, built over the past decade in collaboration with Houstonian Francita Stuart Koelsch Ulmer. This exceptional collection includes standout works by notable artists such as John Constable, John Robert Cozens, Thomas Gainsborough, J.M.W. Turner, and Richard Wilson, whose innovative approaches to watercolor raised its status as an art form and heralded a golden age for the medium.

Through the work of these luminaries and their contemporaries, Picturing Nature reveals how landscape emerged as a distinct artistic genre in England in the late 1700s, then reached its greatest heights the following century, attracting international response and inspiring both artists and collectors at home and abroad. Period publications and artist’s supplies, including drawing manuals and a mid-19th-century Winsor & Newton watercolor box, further illustrate the flowering of the landscape tradition.

Dena M. Woodall, Picturing Nature: The Stuart Collection of 18th- and 19th-Century British Landscapes and Beyond, $35. The online catalogue of the Stuart Collection is available here.

Exhibition | Raphael to Cozens: Drawings from Richard Payne Knight

John Robert Cozens, Mount Etna from the Grotta del Capro; scene in a hollow on a hill-side, at left a group of figures gathered around a fire in a cave, above a clump of trees hiding the moon, beyond a further ridge rises a mountain, ca. 1777–78, watercolour over graphite with gum arabic and scratching out, 357 × 483 mm (London: The British Museum, Oo,4.38).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Opening today at The British Museum:

Raphael to Cozens: Drawings from the Richard Payne Knight Bequest

The British Museum, London, 15 May — 14 September 2025

Raphael, Michelangelo, and Thomas Gainsborough are among the masters whose work will be on display at a new exhibition celebrating a transformative 19th-century bequest. The antiquarian and art collector Richard Payne Knight (1751–1824) bequeathed over a thousand drawings to the British Museum. The superb quality of his collection transformed the Museum’s graphic holdings and established it as a place where visitors could admire old master drawings alongside works of contemporary British art.

Born into a wealthy family of ironmasters from Herefordshire, Payne Knight was educated in the classics and complemented his studies, as many on the Grand Tour did, with extended travels in Italy. There he pursued his interests in ancient civilisations and languages, and formed the aesthetic sensibilities and tastes that would later shape his collecting and writing. His substantial financial means enabled him to acquire the best drawings available on London’s late 18th-century art market. The exhibition explores the breadth of Payne Knight’s intellectual interests through some of the most celebrated works from the bequest. Drawings by Renaissance and Baroque painters like Raphael, Michelangelo, and Claude Lorrain will be shown alongside work by Payne Knight’s contemporaries, including Thomas Gainsborough and John Robert Cozens. Together the drawings reveal Payne Knight’s enthusiasm for landscapes and for the romance of the classical past, as well as his admiration for the verve and spontaneity of the artists whose works he bought.

The exhibition marks the first time that a representative selection of this important bequest has been displayed since its arrival at the British Museum in 1824.

Exhibition | Colour and Line: Watteau Drawings

Antoine Watteau, Four Studies of a Young Woman’s Head, detail, 1716–17, drawing with black, red, and white chalks

(London: The British Museum, 1895,0915.941).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Opening today at The British Museum:

Colour and Line: Watteau Drawings

The British Museum, London, 15 May — 14 September 2025

This Antoine Watteau (probably 1684–1721) was one of the most influential, prolific artists active in 18th-century France. In a short career lasting little more than a decade, he pushed painting in new directions that were to guide generations of French artists, blending genre, mythology and rococo frivolity in works so novel that they heralded a new genre: the fête galante.

Watteau won particular renown for the thousands of drawings he produced during his life. Drawing, as contemporaries realised, was his favourite creative outlet, bringing him ‘much more pleasure than his finished pictures’. He drew incessantly, and developed ideas about the value of drawing that were every bit as original as his paintings. Instead of making figure studies for a picture as academic practice dictated, Watteau drew speculatively, conceiving ideas that might be slotted into a picture months or even years later. The sheets he produced were to be enjoyed in their own right as the first, freshest iterations of ideas that he thought were dulled when translated into paint.

Nowhere were these qualities more appreciated than in Britain, and over the past two centuries British collectors have endowed the British Museum with one of the finest collections of Watteau drawings in the world. Featuring almost every autograph work in the collection, this display is the first exhibition of the Museum’s Watteau holdings to be held since 1980. Its varied contents demonstrate Watteau’s extraordinary talent as a draughtsman, his sophisticated, novel approach to drawing, and the prestige that his graphic works enjoyed among Europe’s connoisseurs.

Exhibition | Mama: From Mary to Merkel

From the press release for the exhibition:

Mama: From Mary to Merkel

Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf, 12 March — 3 August 2025

Curated by Linda Conze, Westrey Page, and Anna Christina Schütz

Marie-Victoire Lemoine, Portrait of Madame de Lucqui with Her Daughter Anne-Aglaé Deluchi, 1800, oil on canvas, 100 × 81 cm (Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, Rau Collection for UNICEF).

The exhibition Mama: From Mary to Merkel explores the many different aspects of motherhood over eight chapters. The focus is on the societal expectations that have always influenced motherhood and are reflected in art, culture, and everyday life. The approximately 120 works on display from the fourteenth century to the present day create a panorama that involves everyone, including fathers and those without children of their own. From the concept of the ‘good mother’ to care work and family configurations, the show illustrates how the role of mother quickly breaks down into different, highly individual perspectives that are nevertheless deeply intertwined in cultural history. A polyphonic sound installation uses pre-recorded voice messages to give space to personal experiences, memories, and visions.

“Everyone has a mother. By placing motherhood at the centre of an exhibition, the Kunstpalast is once again addressing a topic that directly touches the lives of our visitors and that everyone can relate to with their own experiences and opinions. The show combines seriousness with humour and art with everyday life and pop culture— thus tying in with the Kunstpalast’s mission statement on several levels,” says Felix Krämer, general director of the Kunstpalast.

Popular culture and art both emphasise societal expectations of mothers and the role of the GOOD MOTHER. We begin with figures of the Virgin Mary from the fourteenth to the eighteenth centuries. The image of Mary—probably the most prominent mother in Christian culture—remains a symbol of total maternal devotion today. The stereotype of the ‘good’ mother was established in the eighteenth century and is still widespread: contemporary artists in the exhibition explore the efforts involved in attaining this ideal. For a portrait of his mother, Aldo Giannotti (b. 1977) pressed a sign into her hands. The word ‘MOM’ on it only becomes an admiring exclamation of ‘WOW’ when she subjects herself to the strain of hanging upside down from the ceiling. Motherhood is a yardstick by which a woman’s achievement is measured—even if she is not a mother. A well-known example is Angela Merkel (b. 1954): nicknamed ‘Mutti’ (Mum) when she was German Chancellor, she can also be seen as Mother Theresa on the cover of Der Spiegel magazine.

The historical changeability of notions of ‘good’ motherhood is demonstrated by advice books from various decades of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, whose recommendations to mothers are often fundamentally contradictory. ADVICE OR REGULATION—from the Weimar Republic to National Socialism, the early Federal Republic and the GDR to the present-day reunified Germany, this genre is characterised by both consistencies and inconsistencies. A bookshelf in the exhibition gathers advice literature from recent decades and invites visitors to pause and read.

“Ideals and role models, advice, expectations and emotions—the aim of this exhibition is to make the subject of motherhood tangible in all its artistic, cultural historical, social and, of course, highly personal dimensions,” agree the three curators of the show. Linda Conze, Westrey Page and Anna Christina Schütz have approached the topic from different angles, finding mothers and non-mothers in the Kunstpalast collection, supplementing these artists with important, sometimes international loans and bringing everything together to create a narrative. “Connections between the collectively selected works reveal continuities, but also the mutability of images of mothers, which are constantly being reappropriated, reinterpreted, contested and celebrated. We see the show as an invitation to open up a dialogue about care and motherliness and look forward to hearing the audience’s perspectives,” explains the curatorial team.

Looking after children is work. Nevertheless, CARE WORK remains mostly unpaid and has traditionally been automatically assigned to women. With a critical eye, artists have drawn attention to the fact that care is influenced by social norms and class affiliations. For a long time, only poor mothers breastfed their babies themselves, while wealthier women hired wet nurses. Around 1800, the idea that all women should take care of their babies themselves became prevalent; the presence of the biological mother became more important. In the present day, working mothers who focus “too much” on their careers are judged just as much as those who devote themselves entirely to their children and the household. The balancing of care and paid work as well as the role of caregiver and other identities is a recurring theme among the women artists in the exhibition. Several paintings in the exhibition are by Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876–1907), who was always fascinated by motifs of the bond between mother and child. However, she was also apprehensive about the effects of her own motherhood on her artistic work. In her sculpture of a body dissolving in the mechanics of a breast pump, Camille Henrot (b. 1978) focuses on the fine line between providing nourishment and self-sacrifice.

The exhibition delves deeper into the subject of the PLACES OF MOTHERHOOD: historical doll’s house kitchens are brought into dialogue with the video work Semiotics of the Kitchen by Martha Rosler (b. 1943), which examines the distance of the housewife’s domain from intellectual settings. Scottish artist Caroline Walker (b. 1982) portrays mothers with their newborns in the intimate yet isolating domestic sphere. Finnish artist Katharina Bosse (b. 1968) photographs herself in erotically charged poses with her toddler crawling beside her in natural landscapes. In this way, she disrupts the seemingly natural idyll that surrounds motherhood in art and cultural history.

Several women artists use their work to address the fact that the decision to (NOT) HAVE CHILDREN often could not and still cannot be made freely, despite all the progress that has been made. For centuries, female ‘nature’ was defined in a wide variety of societies by a woman’s ability to conceive and bear children. The Virgin Mary, whose life is depicted in Dürer’s Life of the Virgin, is both a female role model and a special case. Her actions are always centred on her son, whom she conceived by divine intervention.

The medical achievements and societal developments of the twentieth century allowed women to emancipate themselves from their socially prescribed destiny for the first time by taking the contraceptive pill or asserting their hard-fought right to terminate a pregnancy. Hannah Höch (1889–1978) paints her struggle with the decision to not have a child by Raoul Hausmann. Nina Hagen’s (b. 1955) protest against the expectations of fulfilling her duty as a mother in the song “Unbeschreiblich Weiblich” (Indescribably Feminine) is juxtaposed with Elina Brotherus’s (b. 1972) confrontation with her own involuntary childlessness.

For a long time, the physical bond between mother and child was unquestioningly viewed as a prerequisite for a motherly love that was regarded as intrinsic. The exhibition also shows that the often positively connoted intimate relationship between mother and child at all ages can also have a potentially traumatic side. In a series of photographs, Leigh Ledare (b. 1976) explores his CLOSENESS to his mother, who confronts her adult son with uncompromising desire. In a video work by performance artist Lerato Shadi (b. 1979), she and her mother lick sugar and salt off each other’s tongues and explore the space between repulsion and affection. The armchair by Italian designer Gaetano Pesce (1939–2024) promises a return to the mother’s womb, with the foot section connected to the main body of the furniture via an ‘umbilical cord’.

In German, the word MUTTERSEELENALLEIN describes the utmost loneliness. Mary, Our Lady of Sorrows, mourning her dead son Jesus Christ, is one of the central motifs in Western art history. Artists have repeatedly made reference to the so-called Pietà, appropriating and reinterpreting it as a motif. The loss of the child is juxtaposed with the loss of the mother, which artists of different generations have sometimes made an autobiographical theme and thus given expression and form to their personal grief. Finally, mutterseelenallein can also refer to anyone who has been denied motherhood, whether due to social norms, physical conditions or decisions that were not made voluntarily.

The exhibition chapter FAMILY CONFIGURATIONS asks what influence family images have on motherhood. In the eighteenth century, the nuclear family rose to become the ideal of the Western world. In this model, the mother is the centre of care, while the father is responsible for financial support. Through processing their own personal or observed experiences, artists have questioned the dominance of this father-mother-child constellation. Alice Neel, who lived apart from her daughter, captures psychological subtleties in her family portraits that resist simple narratives. Oliviero Toscani’s photos for a campaign for the Benetton fashion brand around 1990 challenged conservative notions of family by placing homosexual parents at the centre. Queer lifestyles can inspire ways of thinking in which the burden of care is placed on several shoulders instead of being the sole responsibility of the biological mother. The circle of people who can be mothered also extends beyond biological relatives: foster, step-, adopted children and those in care are also looked after. In the complexity of modern living arrangements, the bond with a pet can be just as important as other relationships. Art reflects the shift from the question ‘Who is the mother?’ to ‘Who is mothering?’

The exhibition chapter FAMILY CONFIGURATIONS asks what influence family images have on motherhood. In the eighteenth century, the nuclear family rose to become the ideal of the Western world. In this model, the mother is the centre of care, while the father is responsible for financial support. Through processing their own personal or observed experiences, artists have questioned the dominance of this father-mother-child constellation. Alice Neel, who lived apart from her daughter, captures psychological subtleties in her family portraits that resist simple narratives. Oliviero Toscani’s photos for a campaign for the Benetton fashion brand around 1990 challenged conservative notions of family by placing homosexual parents at the centre. Queer lifestyles can inspire ways of thinking in which the burden of care is placed on several shoulders instead of being the sole responsibility of the biological mother. The circle of people who can be mothered also extends beyond biological relatives: foster, step-, adopted children and those in care are also looked after. In the complexity of modern living arrangements, the bond with a pet can be just as important as other relationships. Art reflects the shift from the question ‘Who is the mother?’ to ‘Who is mothering?’

The exhibition is an invitation to continue the dialogue about care and motherhood—for example in the diverse accompanying programme, which ranges from a midwife consultation in the exhibition to workshops with various collectives and organisations such as Düsseldorf family centres. One of Germany‘s most prominent mother figures has recorded the audio guide for the exhibition: Marie-Luise Marjan, aka ‘Mutter Beimer’ from the popular TV series Lindenstraße.

Mama: From Mary to Merkel is curated by Linda Conze, Head of Department of Photographs; Westrey Page, Curator Special Projects; and Anna Christina Schütz, Department of Prints and Drawings, Research Associate.

Linda Conze, Westrey Page, and Anna Christina Schütz, ed., Mama: Von Maria bis Merkel (Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2025), 200 pages, ISBN: 978-3777444888, €45.

Exhibition | Rococo & Co: From Nicolas Pineau to Cindy Sherman

Closing soon at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs:

Rococo & Co: From Nicolas Pineau to Cindy Sherman

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, 12 March — 18 May 2025

Curated by Bénédicte Gady, with Turner Edwards and François Gilles

This exhibition celebrates the restoration of a unique collection of nearly 500 drawings from the workshop of the sculptor Nicolas Pineau (1684–1754), one of the main proponents of the Rocaille style, which Europe adopted as Rococo. A practitioner of measured asymmetry and a subtle interplay of solids and voids, Nicolas Pineau excelled in many fields: woodwork, ornamental sculpture, architecture, prints, furniture and silverware. The presentation of this major Rococo figure is extended to include a workshop that plunges the visitor into the heart of the creation of Rococo panelling. Asymmetries, sinuous lines, chinoiserie dreams and animal images illustrate the infinite variations of the Rococo style. Finally, from the 19th to the 21st century, this aesthetic has found numerous echoes, from neo-styles to the most unexpected and playful reinterpretations.

This exhibition celebrates the restoration of a unique collection of nearly 500 drawings from the workshop of the sculptor Nicolas Pineau (1684–1754), one of the main proponents of the Rocaille style, which Europe adopted as Rococo. A practitioner of measured asymmetry and a subtle interplay of solids and voids, Nicolas Pineau excelled in many fields: woodwork, ornamental sculpture, architecture, prints, furniture and silverware. The presentation of this major Rococo figure is extended to include a workshop that plunges the visitor into the heart of the creation of Rococo panelling. Asymmetries, sinuous lines, chinoiserie dreams and animal images illustrate the infinite variations of the Rococo style. Finally, from the 19th to the 21st century, this aesthetic has found numerous echoes, from neo-styles to the most unexpected and playful reinterpretations.

The exhibition explores the evolution of the Rococo style and its reappearance in contemporary design and fashion, including Art Nouveau and psychedelic art. Nearly 200 drawings, pieces of furniture, woodwork, objets d’art, lighting, ceramics, and fashion items engage in a playful dialogue of curves and counter-curves. Nicolas Pineau and Juste Aurèle Meissonnier are joined by Louis Majorelle, Jean Royère, Alessandro Mendini, Mathieu Lehanneur, the fashion designers Tan Giudicelli and Vivienne Westwood, and the artist Cindy Sherman.

Bénédicte Gady, Turner Edwards, and François Gilles, eds., Nicolas Pineau 1684–1754: Un sculpteur de rocaille entre Paris et Saint-Pétersbourg (Paris: Éditions Les Arts Décoratifs, 2025), 504 pages, ISBN: 978-2847425123, €85.

The Burlington Magazine, April 2025

The long 18th century in the April issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 167 (April 2025) | Art in Britain

e d i t o r i a l

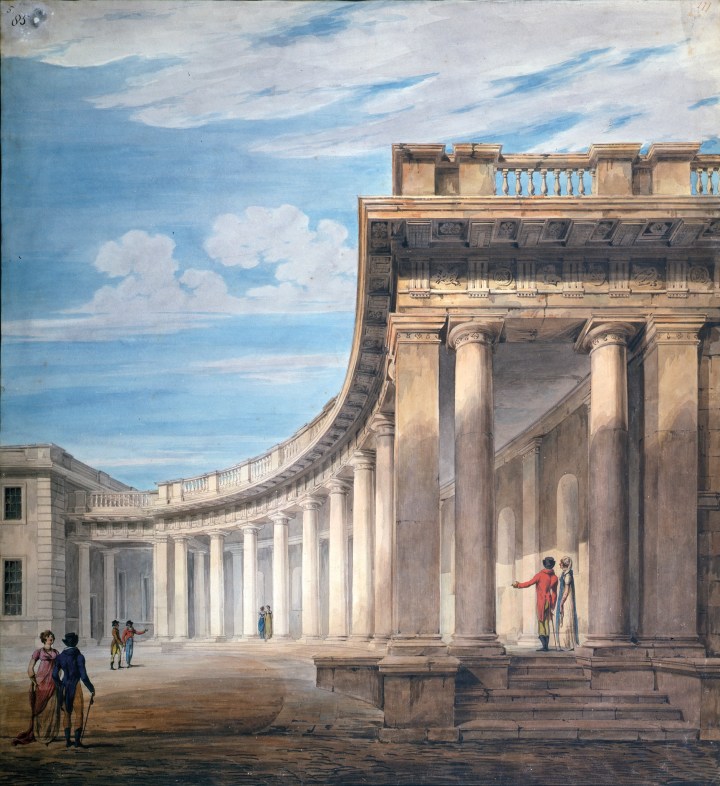

RA Lecture Illustration of the Colonnade at Burlington House, produced by the Soane Office. ca.1806–17, pen, pencil, wash and coloured washes on wove paper, 72 × 67 cm (London: Sir John Soane’s Museum).

• “Boughton’s Heavenly Visions,” pp. 327–29.

Boughton in Northamptonshire is an improbable dream of a house. It is an essay in restrained French Classicism that was gently set into the English countryside in the late seventeenth century, encasing an older building. The house was chiefly the creation of the francophile Ralph, 1st Duke of Montagu (1638–1709), who served as Charles II’s ambassador to the court of Louis XIV. Its most splendid internal feature is the so-called Grand Apartment, which consists of a parade of impressive state rooms.

a r t i c l e s

• William Aslet, “The Discovery of James Gibbs’s Designs for the Façade of Burlington House,” pp. 354–67.

A reassessment of drawings by Gibbs in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, demonstrates that, as well as the stables and service wings and celebrated colonnade, the architect provided an unexecuted design for the façade of Burlington House, London—an aspect of the project with which he has hitherto not been connected. This discovery deepens our understanding of one of the most important townhouse commissions of eighteenth-century Britain and the evolving taste of Lord Burlington.

• Adriana Concin, “A Serendipitous Discovery: A Lost Italian Portrait from Horace Walpole’s Miniature Cabinet,” pp. 368–75.

Among the portraits in Horace Walpole’s renowned collection at Strawberry Hill were a number of images of Bianca Cappello, a Medici grand duchess of some notoriety. Here the rediscovery of a late sixteenth-century Italian miniature once displayed in Walpole’s cabinet is discussed; long thought to depict Cappello, it is now attributed to Lavinia Fontana.

• Edward Town and Jessica David, “The Portraits of Alice Spencer, Countess of Derby, and Her Family by Paul van Somer,” pp. 376–85.

Research into a portrait at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, has revealed the identities of twelve Jacobean portraits attributed to the Flemish painter Paul van Somer. The portraits were probably commissioned by Alice Spencer, Countess of Derby, and create a potent illustration of her dynastic heritage. [The research depends in part upon the eighteenth-century provenance of these portraits.]

r e v i e w s

• Anna Koldeweij, Review of the exhibition Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art (Alte Pinakothek, Munich, 2024–25; Toledo Museum of Art, 2025; MFA, Boston 2025), pp. 393–96.

• Christine Gardner-Dseagu, Review of the exhibition catalogue Penelope, ed. by Alessandra Sarchi and Claudio Franzoni (Electa, 2024), pp. 404–07.

• Andreina D’Agliano, Review of the exhibition catalogue, Magnificence of Rococo: Kaendler’s Meissen Porcelain Figures, ed. by Alfredo Reyes and Claudia Bodinek (Arnoldsche, 2024), pp. 412–14.

• Stephen Lloyd, Review of Susan Sloman, British Portrait Miniatures from the Thomson Collection (Ad Ilissum, 2024), pp. 418–19.

• Natalie Rudd, Review of Discovering Women Sculptors, ed. by Marjorie Trusted and Joanna Barnes (PSSA Publishing, 2023), pp. 422–23.

Exhibition | Pastoral on Paper

Thomas Gainsborough, Landscape with Figures, Herdsman and Cattle at a Pool, and Distant Church, mid- to late 1780s, watercolor and gouache with lead white on beige laid paper, fixed with gum, varnished with mastic (The Clark, gift of the Manton Art Foundation in memory of Sir Edwin and Lady Manton, 2007.8.76).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release for the exhibition:

Pastoral on Paper

The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, 8 March — 15 June 2025

Curated by William Satloff, with Anne Leonard

The idyllic tranquility of the lives of shepherds became a prominent subject in literature, music, and the visual arts during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A new exhibition at the Clark Art Institute, Pastoral on Paper, explores artistic depictions of rural life by considering their representations of the people and animals who inhabited the landscapes. The exhibition is on view in the Eugene V. Thaw Gallery for Works on Paper in the Clark’s Manton Research Center from March 8 until June 15, 2025.

Claude Lorrain, Landscape with the Voyage of Jacob, 1677, oil on canvas (The Clark, 1955.42).

“The Clark’s works on paper collection is rich with beautiful drawings, etchings, and watercolors depicting these pastoral scenes,” said Olivier Meslay, Hardymon Director of the Clark. “We were delighted when our graduate student intern William Satloff proposed the concept of an exhibition that would give us the opportunity to share so many of these exceptional works of art together. Many of the objects in this presentation have not been on view in quite some time, so it will be a wonderful opportunity for our visitors.”

Satloff, a member of the Class of 2025 in the Williams College/Clark Graduate Program in the History of Art, curated the exhibition under the direction of Anne Leonard, the Clark’s Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. Satloff has served as a curatorial intern at the Clark since 2023.

“In the Berkshires, we are fortunate to be surrounded by rolling hills, grazing cows, meandering streams, and picturesque barns,” said Satloff. “Moved by these same features, early modern artists created pastoral landscapes. The exquisite works in this exhibition offer an opportunity for us to reflect on our relationship with land both in art and in the world around us.”

Selected primarily from the Clark’s strong holdings of drawings by Claude Lorrain (French, 1604/5–1682) and Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727–1788) and supplemented with select loans of Dutch Italianate artworks, the exhibition analyzes pastoral imagery to examine how artists construct their own visions of an idealized landscape. This exhibition features thirty-eight works, including nine drawings, three etchings, and one painting by Claude (Lorrain is typically referred to by his first name) and ten Gainsborough drawings.

Claude perfected the genre of idealized landscape, consolidating the developments of sixteenth-century Italian landscape painters and fusing a sensitive observation of nature with the lofty nobility of classical values. He lived and worked in Rome from the 1620s until his death; there, he influenced the Dutch Italianates—northern European artists who traveled to Italy and embraced the local style of landscape painting. A century later Thomas Gainsborough developed a new kind of nostalgic, pastoral landscape, inflecting the naturalism of Claude and the Italianates with a yearning for the bygone days of a simpler country life.

a c c e s s i n g a r c a d i a

The term ‘Arcadia’ derives from the mountainous Greek province of the same name, and according to myth, it was the domain of Pan, the half-man, half-goat satyr who was revered as the god of pastures and woodlands. In antiquity, Arcadia was known for its population of pastoralists—cowherds, goatherds, shepherds, swineherds—who were celebrated across the ancient world for the skillful singing they did while tending their flocks. The Latin poet Virgil wrote an immensely influential set of ten poems, the Eclogues, about the herdsmen of Arcadia.

Agostino Carracci, Omnia Vincit Amor, 1599, engraving on paper (The Clark, gift of Mary Carswell, 2017.11.1).

During the Renaissance, the intellectual movement known as humanism brought renewed interest in the culture—and particularly the poetry—of ancient Greece and Rome. Although Renaissance humanism waned in the sixteenth century, Virgil’s pastoral poetry continued to inspire artists and writers through the nineteenth century and beyond. Over time, ‘Arcadia’ developed into a general term for an idealized vision of rural life.

Agostino Carracci’s (Italian, 1557–1602) engraving, Omnia vincit Amor (1599), is a visual pun derived from a famous line in Virgil’s tenth Eclogue: “Love conquers all.” Amor is the Latin name for Cupid, the god of desire and erotic love. Pan is both the Greek name of Faunus, the shepherd-god of pastures and woodlands, and the Greek word for “all,” which in Latin is “omnia.” Taken together, Cupid’s victorious combat with the goat-legged god becomes a visual translation of Virgil’s poetry.

Nicolaes Berchem, The Cows at the Watering Place (The Cow Drinking), 1680, etching on paper (The Clark, 2023.15).

In The Cows at the Watering Place (The Cow Drinking) (1680), Nicolaes Berchem (Dutch, 1620–1683) conjures a timeless scene of rural life, full of tranquility and contentment. A shepherd has brought his cows and goats to drink from a stream on a warm, bright day. The animals wade and drink in the water, and a group of people lounge leisurely along the bank. The shepherd, recognizable by his long pole, talks with a seated man who has come to fill his jug, while a woman washes her feet in the stream. An overgrown ruin occupies the midground. At the top of this structure, beneath the vines, is a shadowy relief carving of a knight on horseback slaying a monster—an ambiguous reference to a gallant past.

Christoffel Jegher (Flemish, 1596–1652/53) collaborated with the celebrated Baroque artist Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640) to produce the monumental woodcut Rest on the Flight into Egypt (after 1632), which corresponds closely to the right side of Rubens’s oil painting Rest on the Flight to Egypt with Saints (1632–35). Jegher presents the Christ Child sleeping contentedly in the Virgin Mary’s arms at the edge of a dense forest. Two putti, or cherubs, wrestle with a lamb, while a third motions them to be quiet. In the background, Joseph slumbers at the base of a twisting tree while the donkey drinks from a brook.

With its winding river, elegant trees, and grand Romanesque castle, the scene in Landscape with the Voyage of Jacob (1677) is an idealized vision of the countryside near Rome, where Claude spent most of his career. The tiny camels hint at a biblical story, perhaps Jacob’s journey into Canaan, but the other figures scattered across the landscape, such as the herdsman, cows, sheep, dog, and fishermen, give way to another revelation—that the painting is essentially a poetic celebration of the bounty of the natural world.

i d e a l i z e d l a n d s c a p e

Claude and Gainsborough were known to draw landscapes en plein air—meaning that they worked outdoors, directly from the natural environment. Though both artists studied natural features for inspiration, their approach to landscapes varied considerably. Claude’s idealized drawings featured a diffuse light and airy atmosphere aligned with the sensibilities of the Italian countryside. Gainsborough observed nature through a different lens, focusing on the English countryside. Still, each artist endeavored to draw a more pleasing, idealized landscape. Claude often added figures or trees in the foreground to create the illusion of deeper pictorial space. Gainsborough, too, would sometimes make adjustments to the observed landscape—for example, drawing a cluster of trees to one side to balance out the composition.

Claude was fascinated by how ancient and modern Rome melded in the landscape. The early Christian church of Sant’Agnese Fuori le Mura (ca. 300s–600s) attracted Claude on more than one occasion. By the seventeenth century, it was surrounded by farms and open pastures. In A View of Sant’ Agnese Fuori le Mura (1650–55), instead of showing the church surrounded by grazing animals, Claude used hills and trees to obscure any sense of historical specificity. While the identifiable architecture indicates the place from where the artist sketched, the building’s late-antique style imparts a temporal mystique evocative of Arcadia.

Thomas Gainsborough, Extensive Wooded Landscape with a Bridge over a Gorge, Distant Village and Hills, ca. 1786, black and white chalks with stumping on beige laid paper, fixed with skim milk and/or gum (The Clark, 2007.8.75).

Claude often went on sketching expeditions around the Roman countryside in the company of fellow artists. On several occasions, he traveled west from Rome along the Tiber River to the town of Tivoli. Nestled in the Sabine Mountains, Tivoli had long been admired for its ancient ruins and scenic vistas. The German painter Joachim von Sandrart (1606–1688) recounted an excursion he and Claude made to Tivoli: “we began to paint entirely from nature […] the mountains, the grottoes, valleys, and deserted places, the terrible cascades of the Tiber, the temple of Sibyl, and the like.” The Cascades of Tivoli (ca. 1640), on view in this section of the exhibition, depicts such a scene.

Gainsborough usually sketched the English landscape outdoors directly from nature, such as with Extensive Wooded Landscape with a Bridge over a Gorge, Distant Village and Hills (ca. 1786). This practice prompted artist Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–1792) to remark that Gainsborough, his bitter rival, “did not look at nature with a poet’s eye.” As such he went against the prevalent tendency in eighteenth-century England, where most artists derived their landscapes from Virgil’s Eclogues and Claude’s idyllic Italian scenes. Fashionable collectors displayed paintings and prints of idealized Mediterranean landscapes in their homes, setting the trend of “Italian light on English walls.”

r u i n s a n d c o t t a g e s

In pastoral works, architecture is often placed in the midground or background to suggest human habitation of a landscape. In the seventeenth century, pastoral architecture took the form of ruins, indicating that ancient people once held dominion over the land. These ruined buildings—surrounded by overgrown trees and shrubbery—invite viewers to reflect on the greatness of past civilizations, the transience of their glory, and the sublime power of time and nature. In the eighteenth century, pastoral landscapes also came to include cottages, barns, and shacks. By including architectural features within pastoral landscapes, artists may sometimes be making moral, social, and political statements about rural life and land management.

Jean Jacques de Boissieu, The Entrance to a Forest with a Cottage on the Right, 1772, etching and drypoint on laid paper (The Clark, 1993.3).

In A Wooded Landscape with a Classical Temple (ca. 1645), Claude constructs an imaginary landscape by placing ancient-looking architecture amid dense foliage and rolling hills. Although the bridge visible in the background has been identified as Rome’s famous Milvian Bridge (completed in 109 BCE), there are no clear referents for either the fortress pictured behind the bridge or the classical temple on the left.

Bartholomeus Breenbergh’s (Dutch, 1598–1657) Ruins in a Landscape (ca. 1620s) is an early example of Northern European artists’ fascination with ancient architecture. In the shadow of the cavernous ruin, the figures look tiny. Trees grow atop the ruin, juxtaposing the persistence of nature with the ephemerality of Rome’s greatness. Breenbergh moved to Rome in 1619, where he helped found the Roman Society of Dutch and Flemish Painters called the Bentvueghels (active ca. 1620–1720). This intellectual and social group, famous for its drunken initiation rituals, included several prominent Italianate landscape painters, such as Jan Asselijn (Dutch, 1610–1652) and Karel Dujardin (Dutch, 1626–1678).

In Dujardin’s The Ruins of a Temple, in the Foreground Two Men and a Dog (1658), two figures overlook a ruin-strewn landscape from a distance, allowing viewers to insert themselves within the pastoral scene rather than observing it as a spectacle. One of the foreground figures sits with a notebook and a writing instrument in his hand, suggestive of the sketching tours that seventeenth-century artists took throughout the countryside around Rome. Though the figure is representative of the common practice of working outdoors, Dujardin actually created this etching in his studio in the Hague.

Pastoral on Paper is organized by the Clark Art Institute and curated by William Satloff, Class of 2025, Williams Graduate Program in the History of Art.

Exhibition | Japanese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting

Saitō Motonari, Illustrations of Uji Tea Production, 1803, Edo period (1615–1868), handscroll (57 feet) of thirty-two sheets reformatted as a folding album (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023.237).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Now on view at The Met:

The Three Perfections: Japanese Poetry, Calligraphy, and

Painting from the Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 10 August 2024 — 3 August 2025

Curated by John Carpenter

In East Asian cultures, the arts of poetry, calligraphy, and painting are traditionally referred to as the ‘Three Perfections’. This exhibition presents over 160 rare and precious works—all created in Japan over the course of nearly a millennium—that showcase the power and complexity of the three forms of art. Examples include folding screens with poems brushed on sumptuous decorated papers, dynamic calligraphy by Zen monks of medieval Kyoto, hanging scrolls with paintings and inscriptions alluding to Chinese and Japanese literary classics, ceramics used for tea gatherings, and much more. The majority of the works are among the more than 250 examples of Japanese painting and calligraphy donated or promised to The Met by Mary and Cheney Cowles, whose collection is one of the finest and most comprehensive assemblages of Japanese art outside Japan.

The exhibition is made possible by The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Foundation Fund.

Information on the objects exhibited can be found here»

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The catalogue is distributed by Yale UP:

John Carpenter, with Tim Zhang, The Three Perfections: Japanese Poetry, Calligraphy, and Painting (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2025), 320 pages, ISBN: 978-1588397805, $65.

In East Asian cultures, the integration of poetry, painting, and calligraphy, known as the ‘Three Perfections’, is considered the apex of artistic expression. This sumptuous book explores 1,000 years of Japanese art through more than 100 works—hanging scrolls, folding screens, handscrolls, and albums—from the Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. John T. Carpenter provides an engaging history of these interrelated disciplines and shows evidence of intellectual exchange between Chinese and Japanese artists in works with poetry in both languages, calligraphies in Chinese brushed by Japanese Zen monks, and examples of Japanese paintings pictorializing scenes from Chinese literature and legend. Many of the works featured, including Japanese poetic forms, Chinese verses, and Zen Buddhist sayings, are deciphered and translated here for the first time, providing readers with a better understanding of each work’s rich and layered meaning. Highlighting the talents of such masters as Musō Soseki, Sesson Shūkei, Jiun Onkō, Ryōkan Taigu, Ike no Taiga, and Yosa Buson, this book celebrates the power of brush-written calligraphy and its complex visual synergy with painted images.

In East Asian cultures, the integration of poetry, painting, and calligraphy, known as the ‘Three Perfections’, is considered the apex of artistic expression. This sumptuous book explores 1,000 years of Japanese art through more than 100 works—hanging scrolls, folding screens, handscrolls, and albums—from the Mary and Cheney Cowles Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. John T. Carpenter provides an engaging history of these interrelated disciplines and shows evidence of intellectual exchange between Chinese and Japanese artists in works with poetry in both languages, calligraphies in Chinese brushed by Japanese Zen monks, and examples of Japanese paintings pictorializing scenes from Chinese literature and legend. Many of the works featured, including Japanese poetic forms, Chinese verses, and Zen Buddhist sayings, are deciphered and translated here for the first time, providing readers with a better understanding of each work’s rich and layered meaning. Highlighting the talents of such masters as Musō Soseki, Sesson Shūkei, Jiun Onkō, Ryōkan Taigu, Ike no Taiga, and Yosa Buson, this book celebrates the power of brush-written calligraphy and its complex visual synergy with painted images.

John T. Carpenter is the Mary Griggs Burke Curator of Japanese Art in the Department of Asian Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. He has been with The Met since 2011. From 1999 to 2011, he taught the history of Japanese art at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, and served as head of the London office of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures. He has published widely on Japanese art, especially in the areas of calligraphy, painting, and woodblock prints, and has helped organize numerous exhibitions at the Museum, including Designing Nature (2012–13), Brush Writing in the Arts of Japan (2013–14), Celebrating the Arts of Japan (2015–17), The Poetry of Nature (2018–2019), and The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Illuminated (2019).

Tim T. Zhang is Research Associate of Asian Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

c o n t e n t s

Director’s Foreword

Preface

Becoming a Collector of Japanese Art — Cheney Cowles

Acknowledgments

Note to the Reader

Introduction

Inscribing and Painting Poetry: The Three Perfections in Japanese Art — John T. Carpenter

Catalogue

1 Courtly Calligraphy Styles: Transcribing Poetry in the Heian Palace

Entries 1–13

2 Spiritual Traces of Ink: Calligraphies by Medieval Zen Monks

Entries 14–31

3 Reinvigorating Classical Poetry: Brush Writing in Early Modern Times

Entries 32–59

4 Poems of Enlightenment: Edo-Period Zen Calligraphy

Entries 60–84

5 China-Themed Paintings: Literati Art of Later Edo Japan

Entries 85–111

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Credits

Exhibition | 100 Ideas of Happiness

Moon Jar, white porcelain, Joseon Dynasty, 18th century

(Seoul: National Museum of Korea)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release for the exhibition:

100 Ideas of Happiness: Art Treasures from Korea

Residenzschloss, Dresden, 15 March — 10 August 2025

For the first time in over 25 years, precious artifacts that give an overview of Korean art and cultural history are on display in Germany. The exhibition 100 Ideas of Happiness takes place thanks to a cooperation with the National Museum of Korea, which is supported by the Korea Foundation.

Embedded in the baroque Paraderäume (Royal State Apartments) and the Neues Grünes Gewölbe (New Green Vault) of the Dresden Residenzschloss (Royal Palace), the show opens up an exciting dialogue between cultures. The central theme is the timeless question of the various ideas of happiness—including the desire for eternal life, peace in this world and the next, inner strength or pure joie de vivre— as expressed in works of art through colours, symbols, and the choice of subject matter.

On display are around 180 outstanding individual objects and groups of objects, including valuable grave goods, precious jewellery, royal robes, and exquisite porcelain from several eras of Korean history. The objects give a multifaceted impression of Korea’s artistic traditions from the time of the ancient kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla (57 BC–935 AD) to the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897). Numerous loans are on show for the first time in Europe. The central themes of the presentation are ancient funerary traditions, the role of Buddhism and Confucianism as state-endorsed religions, the legacy of ceramic art, and the significance of the traditional Korean attire, the Hanbok, in the past and present.

On display are around 180 outstanding individual objects and groups of objects, including valuable grave goods, precious jewellery, royal robes, and exquisite porcelain from several eras of Korean history. The objects give a multifaceted impression of Korea’s artistic traditions from the time of the ancient kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla (57 BC–935 AD) to the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1897). Numerous loans are on show for the first time in Europe. The central themes of the presentation are ancient funerary traditions, the role of Buddhism and Confucianism as state-endorsed religions, the legacy of ceramic art, and the significance of the traditional Korean attire, the Hanbok, in the past and present.

A tour of the exhibition through the Paraderäume concludes with a selection of Korean artworks from the ethnographic collections of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections). These include folding screens, armour, and weapons collected by German travellers in Korea at the beginning of the 19th century. They offer valuable insights into Korea at that time and document the beginnings of a cultural exchange between Korea and Germany. An important item is the folding screen from the GRASSI Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig. Its title is 100 Ideas for Happiness and Longevity and gave the exhibition its name.

The second exhibition venue within the Residenzschloss is located in the Sponsel Room of the Neues Grünes Gewölbe. Surrounded by the treasures of Augustus the Strong, a selection of precious gold jewellery from the royal tombs of the Silla Dynasty is displayed there. These objects—including the famous gold crown from Geumgwanchong, one of the most important royal tombs in Gyeongju, the ancient capital of the Silla kingdom—are among Korea’s national treasures. An elaborately decorated belt made of pure gold, a wing-shaped headdress, and magnificent earrings and rings (presented in the exhibition as an ensemble for the first time in many years) also come from this tomb. They are cultural and historical testimonies to the great significance of the Silla Kingdom.

Claudia Brink and Sojin Baik, 100 Ideen von Glück: Kunstschätze aus Korea (Dresden: Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 2025), 216 pages, ISBN: 978-3954988631, €34.

Exhibition | Silver from Modest to Majestic

Daniel Garnier, Silver Chandelier, made in London, 1691–97, silver and iron (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase, 1938-42). Fashioned for King William III of England sometime between 1691 and 1697, this chandelier hung at St. James’s Palace in London. It is believed to have been sold for its silver value by King George III when it was seen as outdated. After remaining in private hands for more than a century, it was auctioned in 1924 to William Randolph Hearst, the prominent American newspaperman. Colonial Williamsburg acquired the chandelier shortly before WWII.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release (3 April 2025) for the exhibition:

Silver from Modest to Majestic

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, 24 May 2025 — 24 May 2028

Work is currently underway at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg on a new exhibition featuring more than 120 objects from the museum’s extensive collection of 17th- to 19th-century silver. Silver from Modest to Majestic will be on view in the museum’s newly relocated Mary Jewett Gaiser Silver Gallery, on the main floor of the museum until 24 May 2028.

The exhibition’s scope is wide-ranging, from a 49-lb chandelier made for a monarch to a simple spoon made by a Williamsburg silversmith, all displayed in brilliantly lit cases against dark blue backgrounds. While silver has long been associated with wealth and aristocracy, the items featured in this exhibition were crafted for use in nearly every setting imaginable ranging from churches, classrooms, and kitchens to businesses, battlefields, and bedrooms. One thing that every piece on display has in common is a powerful story. Some are objects of great beauty created with the highest level of skill, while others have lengthy pedigrees. Knowing who made a piece and who used it lets Colonial Williamsburg curators pinpoint that object in a time and a place, and then bring it forward through history, allowing it to tell its tale.

“Collecting objects where we know the ‘who, when, and where’ of their manufacture, plus their provenance, allows us to exhibit silver items which transcend the differences between artistic, historical, and functional,” said Erik Goldstein, Colonial Williamsburg’s senior curator of mechanical arts, metals and numismatics. “These particular objects are the pinnacle of early silver, no matter how humble they may be.”

This new exhibition replaces the museum’s previous silver exhibition, Silver from Mine to Masterpiece, which was on view from 2015 to 2023. While the former exhibition had a larger percentage of British silver, nearly half of the objects on display in the new exhibition are examples of early American-made silver, many of which were created for everyday use by ordinary people. Early colonists originally relied on imported British silver wares, but over time, the innovation, skill, and entrepreneurship of those early American tradespeople resulted in the establishment of a robust and exciting cohort of American silversmiths producing items that were touched by everyone from elite to enslaved individuals.

“Our collection of British silver is justly famous, but our decision to build a collection of American silver terrifically advances the museums’ goal of telling the varied stories of so many different craftspeople and consumers, each of whom influenced the tastes and styles of colonial America,” said Grahame Long, executive director of collections and deputy chief curator.

Punch Ladle, possibly made in Williamsburg, ca.1740–70, silver and wood (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of A. Jefferson Lewis III in memory of Elizabeth Neville Miller and Margaret Prentis Miller Conner, 2023-101; photo by Jason Copes). This worn and lovingly preserved ladle, believed to have been made locally, descended in the Prentis family of Williamsburg.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Visitors to Colonial Williamsburg will experience firsthand how the pieces featured in Silver from Modest to Majestic connect to the lives of Williamsburg’s 18th-century residents. One item in the exhibition—a silver punch ladle, owned by the Prentis family of Williamsburg and passed down in the family for 250 years—served as the model for a reproduction punch ladle created by Williamsburg’s silversmiths that visitors will find in the corner cupboard at the Williamsburg Bray School after it opens to the public in June 2025. Archaeological records show that Ann Wager, headmistress of the Williamsburg Bray School, had punch wares.

“Having the Prentis family’s original ladle gave us a wonderful opportunity to reproduce a piece that we know was used by an 18th-century Williamsburg family and put it in the context of the Bray School where it helps to tell that story,” said Goldstein.

Caddy Spoon, marked by Hester Bateman (1708–1794), London, 1789–90, silver (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Gift of Mr. E. Palmer Taylor, 1998-92; photo by Jason Copes). Many now-anonymous British women worked in the silversmithing trade, producing small items like buttons or finishing and polishing larger wares. Standing out is Hester Bateman, who ran a thriving silversmith business after the death of her husband. She specialized in affordable items aimed at the rising middle class. When Bateman retired in 1790, the business was carried on by her sons and one of her daughters-in-law.

Other recently acquired highlights of the silver exhibition include the earliest-known Virginia-made horse racing trophy awarded to a horse named Madison in 1810; an Indian Peace medal struck by the U.S Mint during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency as a diplomatic gift for a Native American chief; and a church communion cup made in Massachusetts around 1670, the earliest piece of American silver in the Foundation’s collection. These pieces will join some of the extraordinary older items from the collection including a cache of British silver made between 1765 and 1771, which was discovered in 1961 in a field near Suffolk, Virginia. While the origins of the buried treasure, and the reason that no one ever returned to retrieve it, remain unknown to this day, this collection is a reminder of the high monetary—and not just aesthetic―value of silver in early America.

The objects on display in Silver from Modest to Majestic represent the work of a few dozen known silversmiths including Paul Revere (1735–1818), a hero of the American Revolution who learned the trade of silversmithing from his father; Myer Myers (1723–1795), the son of a Jewish refugee who became known as the leading silversmith of New York; and Hester Bateman (1708–1794), a female silversmith in London who ran a thriving business after the death of her husband, specializing in affordable items aimed at the rising middle class. Many items in the exhibition are unmarked, made by unknown makers including enslaved silversmiths. Even the items that are credited to known makers could have been made by smiths employed, apprenticed, or enslaved to the master of the shop. To learn exactly how the items in Silver from Modest to Majestic were created, visitors to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg can visit the Silversmith shop in Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area where artisan historians preserve the trade by practicing it as their 18th-century counterparts would have.

This exhibition is generously funded by The Mary Jewett Gaiser Silver Study Gallery Endowment. Admission to the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg is free.

leave a comment