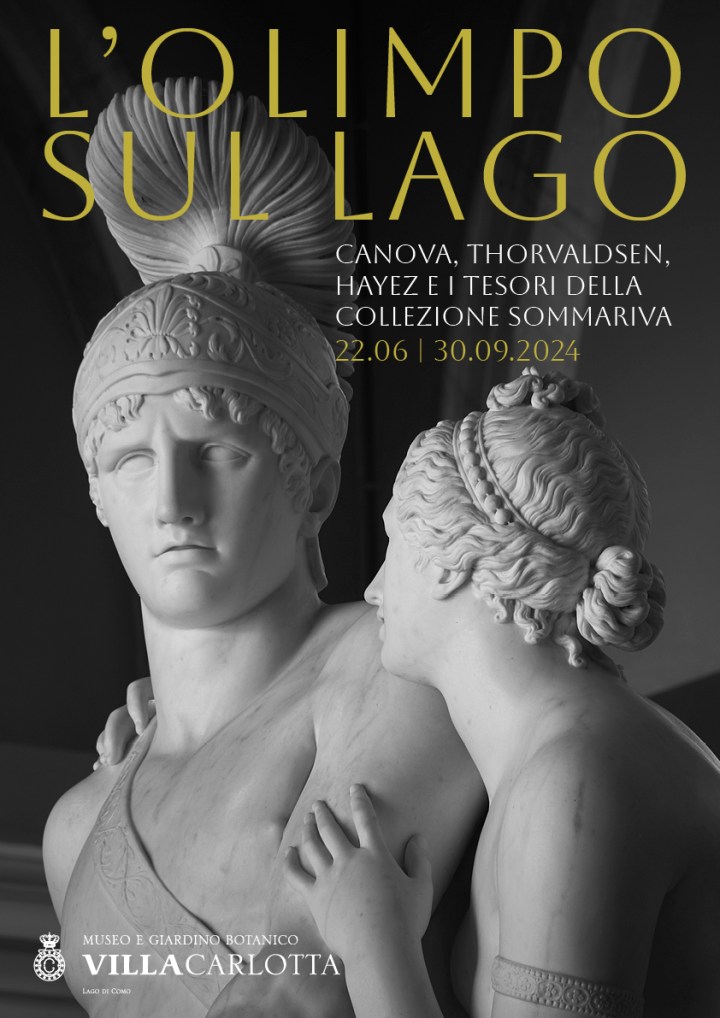

Exhibition | Olympus on the Lake: Canova, Thorvaldsen, Hayez

Jean-Baptiste Joseph Wicar, Virgil Reading the Sixth Canto of the Aeneid, 1818–21, oil on canvas

(Tremezzo: Museo di Villa Carlotta)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Now on view at Villa Carlotta (with an English description available here) . . .

Olympus on the Lake: Canova, Thorvaldsen, Hayez, and the Treasures of the Sommariva Collection

Villa Carlotta, Tremezzo (on Lake Como), 22 June – 30 September 2024

Abile politico e potente braccio destro di Napoleone a Milano, Giovanni Battista Sommariva (1762–1826) è stato uno dei maggiori e più celebri collezionisti tra l’Impero e la Restaurazione. Approfittando di quei tempi di rapidi e radicali cambiamenti, nel 1802—quando si interruppe la sua breve ma fulminante carriera—era ormai riuscito a costruirsi una immensa fortuna.

La sua leggendaria raccolta era una delle più importanti dell’epoca, insieme a quelle dei familiari di Napoleone, in particolare dell’imperatrice Josephine. Divisa tra il suo palazzo a Parigi, in uno dei quartieri più alla moda della città, e la villa di Tremezzo sul Lago di Como (oggi Villa Carlotta), vantava dipinti antichi e capolavori dei maggiori artisti dell’epoca—David, Prud’hon, Girodet, Wicar, Appiani, Bossi, Hayez—oltre a una infinità di preziosi oggetti d’arte. Soprattutto per la presenza a Villa Sommariva delle opere di Canova e degli splendidi marmi di Thorvaldsen, accorrevano viaggiatori da tutto il mondo, tra cui personaggi illustri come Stendhal, Lady Morgan, Flaubert. Attraverso una selezione delle opere più famose di quella straordinaria collezione—sculture, dipinti, stampe, gioielli e miniature—Villa Carlotta celebra un magnifico protagonista della propria storia e un grande mecenate di statura europea.

La sua leggendaria raccolta era una delle più importanti dell’epoca, insieme a quelle dei familiari di Napoleone, in particolare dell’imperatrice Josephine. Divisa tra il suo palazzo a Parigi, in uno dei quartieri più alla moda della città, e la villa di Tremezzo sul Lago di Como (oggi Villa Carlotta), vantava dipinti antichi e capolavori dei maggiori artisti dell’epoca—David, Prud’hon, Girodet, Wicar, Appiani, Bossi, Hayez—oltre a una infinità di preziosi oggetti d’arte. Soprattutto per la presenza a Villa Sommariva delle opere di Canova e degli splendidi marmi di Thorvaldsen, accorrevano viaggiatori da tutto il mondo, tra cui personaggi illustri come Stendhal, Lady Morgan, Flaubert. Attraverso una selezione delle opere più famose di quella straordinaria collezione—sculture, dipinti, stampe, gioielli e miniature—Villa Carlotta celebra un magnifico protagonista della propria storia e un grande mecenate di statura europea.

Per tutta la durata della mostra L’Olimpo sul lago, è possibile visitare presso il Museo del Paesaggio del Lago di Como (Tremezzina) l’esposizione Paesaggio sublime: Il Lago di Como all’epoca di Giovanni Battista Sommariva (1801–1826) che esporrà incisioni, tempere e acquerelli della prima a metà del XIX secolo con il proposito di evocare l’aspetto del lago e dei suoi borghi al tempo di Giovanni Battista Sommariva.

Fernando Mazzocca, Maria Angela Previtera, and Elena Lissoni, eds., L’Olimpo sul lago: Canova, Thorvaldsen, Hayez e i tesori della Collezione Sommariva (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2024), 352 pages, ISBN 978-8836658336, €35.

Exhibition | Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy

Opening in October at The Morgan:

Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy

The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, 25 October 2024 — 4 May 2025

Organized by Philip Palmer and Erica Ciallela

The incredible story of the first director of the Morgan Library: a visionary Black woman who walked confidently in an early 20th-century man’s world of wealth and privilege

The incredible story of the first director of the Morgan Library: a visionary Black woman who walked confidently in an early 20th-century man’s world of wealth and privilege

To mark the 2024 centenary of its life as a public institution, the Morgan Library & Museum will present a major exhibition devoted to the life and career of its inaugural director, Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950). Widely recognized as an authority on illuminated manuscripts and deeply respected as a cultural heritage executive, Greene was one of the most prominent librarians in American history.

She was the daughter of Genevieve Ida Fleet Greener (1849–1941) and Richard T. Greener (1844–1922), the first Black graduate of Harvard College, and was at birth known by a different name: Belle Marion Greener. After her parents separated in the 1890s, her mother changed the family surname to Greene, Belle and her brother adopted variations of the middle name da Costa, and the family began to pass as White in a racist and segregated America.

Greene is well known for the instrumental role she played in building the exceptional collection of rare books and manuscripts formed by American financier J. Pierpont Morgan, who hired her as his personal librarian in 1905. After Morgan’s death in 1913, Greene continued as the librarian of his son and heir, J.P. Morgan Jr., who would transform his father’s Library into a public institution in 1924. But her career as director of what was then known as the Pierpont Morgan Library―a leadership role she held for twenty-four years―is less well understood, as are aspects of her education, private collecting, and dense social and professional networks.

The exhibition will trace Greene’s storied life, from her roots in a predominantly Black community in Washington, D.C., to her distinguished career at the helm of one of the world’s great research libraries. Through extraordinary objects―from medieval manuscripts and rare printed books to archival records and portraits―the exhibition will demonstrate the confidence and savvy Greene brought to her roles as librarian, scholar, curator, and cultural executive, and honor her enduring legacy.

This exhibition is organized by Philip Palmer, Robert H. Taylor Curator and Department Head of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, and Erica Ciallela, Exhibition Project Curator.

Erica Ciallela and Philip Palmer, eds., Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy (New York: DelMonico Books, 2024), 304 pages, ISBN: 978-1636811352, $50. With a foreword by Colin Bailey, an afterword by Tamar Evangelestia-Dougherty, and contributions by Araceli Bremauntz-Enriquez, Julia Charles-Linen, Erica Ciallela, Rhonda Evans, Anne-Marie Eze, Daria Rose Foner, Jiemi Gao, Juliana Amorim Goskes, Gail Levin, Philip Palmer, Deborah Parker, and Deborah Willis.

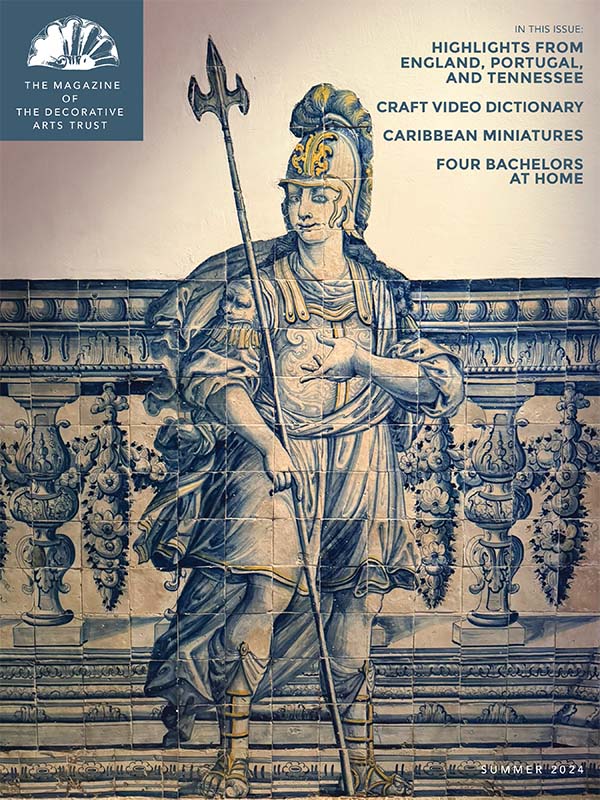

The Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust, Summer 2024

The Decorative Arts Trust has shared select articles from the summer issue of their member magazine as online articles for all to enjoy. The following articles are related to the 18th century:

The Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust, Summer 2024

• “A Primer on Portugal” by Matthew A. Thurlow Link»

• “A Primer on Portugal” by Matthew A. Thurlow Link»

• “Saltram’s Saloon: Adam, Chippendale, and Reynolds in England’s West Country” by Catherine Carlisle Link»

• “Understanding Craft: A New Digital Tool Debuts” by Emily Zaiden Link»

• “Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800: Highlights from LACMA’s Collection” by the Saint Louis Art Museum Link»

• “Painted Walls: New Virtual Museum Offers an Immersive Experience” by by Margaret Gaertner and Kathleen Criscitiello Link»

• “Seafaring Portraits in Bermuda and the Atlantic Basin” by Damiët Schneeweisz Link»

• “Summer Reading Recommendation: Ceramic Art” by Jessie Dean Link»

The printed Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust is mailed to Trust members twice per year. Memberships start at $50, with $25 memberships for students.

Pictured: The magazine cover features a detail of wall tile from the stair hall of the Palácio Azurara in Lisbon, home of the Fundação Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva’s decorative arts museum. Bartholomeu Antunes, Tile with the Figure of a Praetorian Guard, 1730–40, Lisbon. Earthenware tile with blue and yellow decoration.

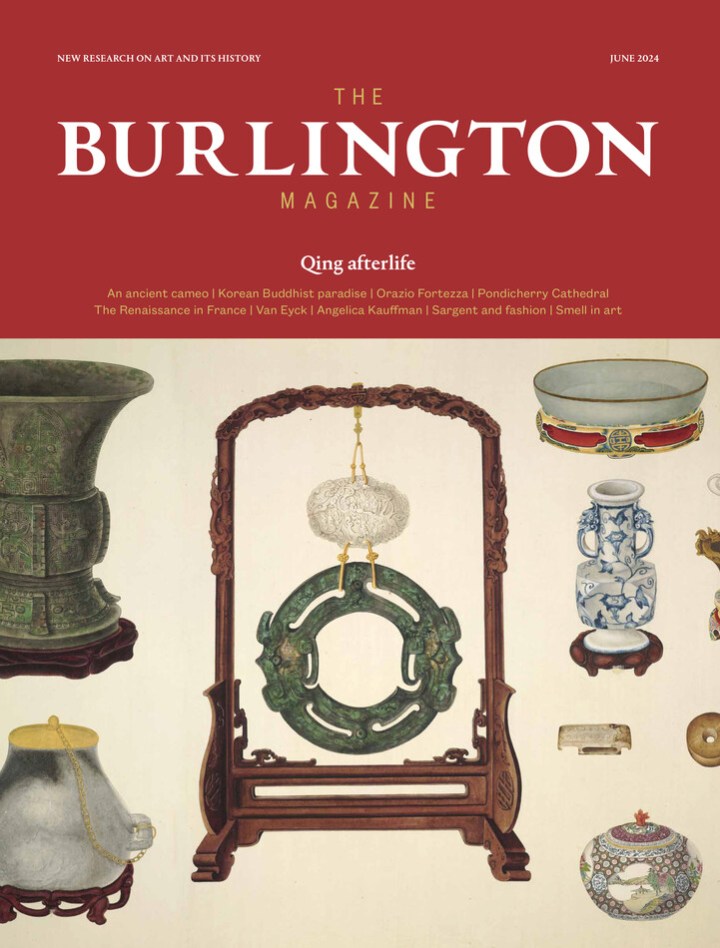

The Burlington Magazine, June 2024

Summer is for falling behind . . . and for catching up . . . The long 18th century in the June issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 166 (June 2024)

e d i t o r i a l

• “La Serenissima,” p, 543.

• “La Serenissima,” p, 543.

Henry James famously wrote in his Italian Hours (1909) that there is nothing more to be said about Venice. As so much ink has been spilt over its charms you can see his point. However, James then proceeded to rhapsodise at length about its beauty; and it is imperative that we, similarly, keep talking and writing and championing it, not least because all that it represents seems to be more precious and precarious than ever.

a r t i c l e s

• Ittai Gradel, “Nothing To Do with Menander: A Rediscovered Roman Cameo from the Caylus Collection,” pp. 546–53.

A Roman cameo published in 1752, but since lost, has been rediscovered. It shows actors rehearsing The Pimp by Posidippus, who portrait is included on the cameo. All other identifiable scenes of comedies in Roman art depict plays by Menander, the most popular Greek comic poet on the Roman stage.

• Gauvin Alexander Bailey, “The Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-la-Conception, Pondicherry,” pp. 580–95.

When the cathedral at Pondicherry, the most ambitious in French India, was begun in 1771, its anonymous designer was obliged to make allowance for separation of the castes, despite a papal edict that they must attend public worship together. The cathedral was completed with the construction of its west facade in 1788–91; its design was based on seventeenth-century Parisian models and is here attributed to the engineer-architect François-Anne-Maire Rapine de Saxy.

• Ricarda Brosch, “The Art of Qing Imperial Afterlife: The Pictures of Ancient Playthings (Guwantu 古玩圖) Revisited,” pp. 596–611.

Two magnificent eighteenth-century handscrolls depict myriad precious objects made of jade, bronze, porcelain, glass, and bamboo. A novel interpretation of their function suggests that the illustrations were originally for wall decorations and remounted as scrolls for the Yongzheng Emperor’s tomb. The paintings’ remediation and repurposing offer a compelling example of the art of Qing imperial afterlife.

r e v i e w s

• Johnny Yarker, Review of the exhibition Angelica Kauffman (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2024), pp. 620–23.

• William Barcham, Review of Martin Gayford, Venice: City of Pictures (Thames & Hudson, 2023), p. 653.

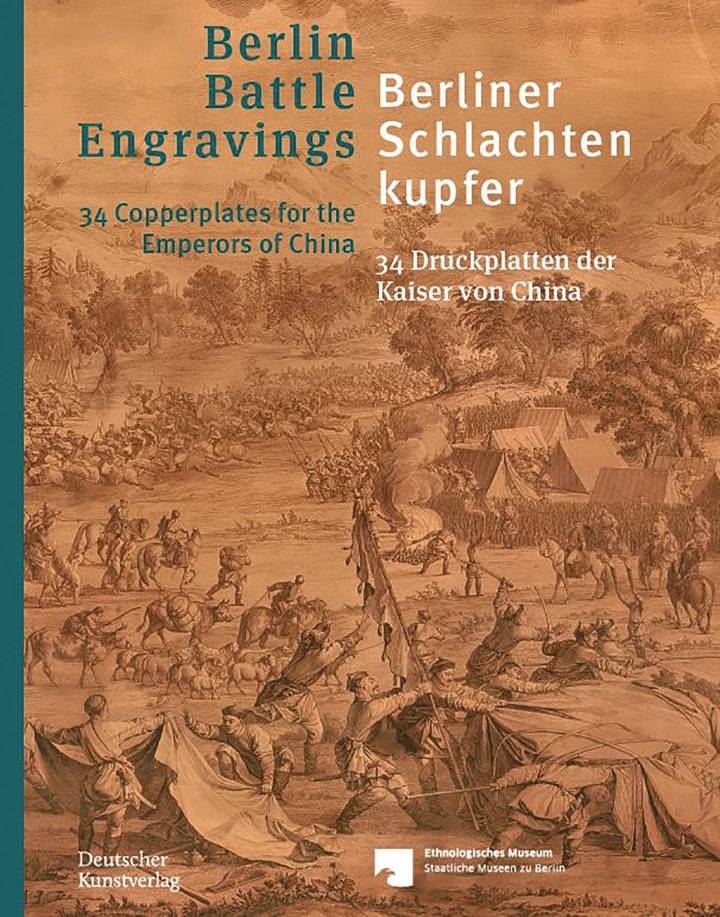

• Lianming Wang, Review of Henriette Lavaulx-Vrécourt and Niklas Leverenz, Berliner Schlachtenkupfer: 34 Druckplatten der Kaiser von China / Berlin Battle Engravings: 34 Copperplates for the Emperors of China (Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021), pp. 654–55.

• Amina Wright, Review of Frédéric Ogée, Thomas Lawrence: Le génie du portrait anglais (Cohen & Cohen, 2022), pp. 655–56.

• Barry Bergdoll, Review of Didem Ekici, Patricia Blessing, Basile Baudez, eds., Textile in Architecture: From the Middle Ages to Modernism (Routledge, 2023), pp. 662–63.

Exhibition | Living with Sculpture: Presence and Power

From the press release for the exhibition:

Living with Sculpture: Presence and Power in Europe, 1400–1750

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire, 23 March 2024 — 22 March 2025

Curated by Elizabeth Rice Mattison and Ashley Offill

The Hood Museum of Art presents Living with Sculpture: Presence and Power in Europe, 1400–1750, on view from 23 March 2024 until 22 March 2025. Drawing on the wealth of the Hood Museum’s permanent collection, the exhibition contributes to the field’s understanding of the role of sculpture in everyday life, historically and today. Whether given as tokens of affection, cast to memorialize important events, designed to promote faith, or used to write a letter, these sculptures engaged their spectators in dialogues of devotion, authority, and intimacy.

Living with Sculpture is curated by two scholars at the Hood Museum of Art: Elizabeth Rice Mattison, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Academic Programming and Curator of European Art, and Ashley B. Offill, Curator of Collections. It includes 164 objects in two galleries and is accompanied by a major publication of the same title.

Sculpture enlivened private and public spaces in medieval and Renaissance Europe, contributing to presentations of identity, practices of devotion, and promotions of nationhood. Featuring objects made across the continent, this exhibition examines the significance of sculpture between 1400 and 1750, an era of profound cultural and social change. Amid war, colonization, religious conflict, academic upheaval, and social stratification, these works of art ornamented homes, altars, libraries, and collections.

The role of sculpture as a commemorative and connective tool is newly evident in today’s debates about monuments and cultural patrimony. Sculpture manipulates notions of history, forges bonds between distant places, and promotes future actions, as this exhibition shows. Bringing this often-cerebral area of study down to earth, exhibition curators Elizabeth Rice Mattison and Ashley Offill note, “In examining a group of historic objects, this exhibition highlights the way that the material things with which we surround ourselves are critical to developing our personal identities and our relationships with one another. As curators, we lived with these objects during this project, gaining insight into the works and the people who owned them. The choice of a laurel wreath or a cross on a medal was, in many ways, just as informative back then as a social media bio is today.”

Recent examinations of sculpture suggest its singular presence and power for its makers, patrons, and audiences. The dynamism of sculpture became particularly evident in the 15th and 16th centuries with the explosion of interest in purchasing mass-produced objects such as plaquettes and small-scale bronzes. Technological innovations in making sculpture allowed artists to expand their markets and create new types of artwork.

Organized thematically, this exhibition focuses on small-scale sculptures for everyday spaces. With these works, artists could enhance their status and promote their creativity. Meanwhile, useful sculptures like locks and inkwells communicated their owners’ identities and prestige. In collecting sculptures, patrons activated their social connections. Sculpture also facilitated access to the divine, through objects that focused prayer and encouraged tactile connection with God. Similarly, sculptures forged a sense of history, recording contemporary events and promoting ideas about the past. Together, the sculptures presented here attest to how objects in bronze, wood, or stone gave meaning to people’s lives in early modern Europe.

This exhibition and its corresponding catalogue are organized by the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, and generously supported by the Leon C. 1927, Charles L. 1955, and Andrew J. 1984 Greenebaum Fund, and by grants from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation.

The catalogue is distributed by Penn State UP:

Elizabeth Rice Mattison and Ashley Offill, Living with Sculpture: Presence and Power in Europe, 1400–1750 (Hanover: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, 2024), 340 pages, ISBN: 978-0944722558, $50.

The accompanying publication includes five thematic essays, extended catalogue entries for 99 objects, and an illustrated checklist of 114 additional objects from the important collection of early modern sculpture at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth. The book is published by the Hood Museum of Art, distributed by The Pennsylvania State University Press, and produced by Marquand Books, Seattle.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Exhibition Colloquium | Living with Sculpture

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, 7 September 2024

In connection with the exhibition, this colloquium brings together scholars and curators from around the Northeast to discuss how audiences, patrons, and makers engaged with sculpture in the Middle Ages and early modern period. Ranging from twelfth-century Spain to seventeenth-century Rome, the discussion topics will offer an in-depth examination of making and living with sculpture. The day will include a tour of the exhibition led by its curators, Elizabeth Rice Mattison and Ashley Offill. Check-in opens at 9.30am, and the program will begin at 10.00. The colloquium itself is free, by registration at Eventbrite. A limited number of hotel rooms are available at the Hanover Inn under the block ‘Living with Sculpture’. Please reserve before August 7.

p r e s e n t a t i o n s

• Elizabeth Lastra (Vassar College), Threads of Power and Identity: Exploring Textile Motifs in Sculpture at the Romanesque Monastery of San Zoilo

• Kelley Helmstutler Di Dio (University of Vermont), Seeing Two Sides of the Same Coin: Leone Leoni’s Circle and their Medals in the Hood Museum

• Lara Yeager-Crasselt (Baltimore Museum of Art), François Duquesnoy’s Funerary Monument to the Painter Jacob de Hase: Untangling Flemish Expatriate Networks in Rome

• Laura Tillery (Hamilton College), The Armed Image of Olav Lorenzo Buonanno, University of Massachusetts, Boston, Living with Imaginary Sculptures

• Miya Tokumitsu (Davison Art Center, Wesleyan), Gothic to Grotesque: Sculptural Ornament in the Prints of Lucas van Leyden

• Nicola Camerlenghi (Dartmouth College), Living Sculptures in the Renaissance Streets of Rome

Exhibition | Worlds Collide: Archaeology and Global Trade

From the press release for the exhibition:

Worlds Collide: Archaeology and Global Trade in Williamsburg

DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, 7 September 2024 — 2 January 2027

Madeira Decanter, England, ca. 1750, colorless leaded glass, excavated at Wetherburn’s Tavern (Colonial Williamsburg).

We live in an international world where people, commerce, ideas, and traditions cross borders on a daily basis, and this concept is hardly new. As a new exhibition will show at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, one of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, these aspects of life were just as evident in the 18th century. Worlds Collide: Archaeology and Global Trade in Williamsburg will reveal the colonial capitol of Virginia to have been a thriving, urban center coursing with people and goods from all over the world as evidenced through approximately 225 archaeological artifacts curated by Colonial Williamsburg’s renowned team of archaeologists. From Spanish coins to Chinese porcelain, punch bowls with political slogans to printer’s type and a dog’s tag, botanicals and glass, the objects vary widely and represent a mere fraction of the over 60 million objects in the collection. Through the opportunity to recover and understand these artifacts, which are the material remains of daily lives of residents from Virginia and abroad, the evidence shows the collision of worlds that defined the town.

“Written documents, works of art, and other sources of information about the past invariably carry the biases of their creators,” said Ron Hurst, the Foundation’s chief mission officer, “but archaeological deposits offer a largely unbiased view of past civilizations. This exhibition illustrates clearly that worldwide commerce is nothing new and touched most parts of the north Atlantic world in the 18th century, even in a place as small as Williamsburg, Virginia.”

Cities such as Williamsburg were hubs where the numerous customs, styles, and tastes of its inhabitants clashed, melded, and evolved through daily interactions. Eighteenth-century Williamsburg was home to people representing a broad mix of economic status, genders, and ages. In addition to Indigenous people and those of European descent, more than half of the town’s population was African or African American, the majority of which was enslaved. The objects seen in Worlds Collide reflect just as much the daily lives of these men, women and children as they do the individuals who enslaved them. To illuminate the diversity of these facets of everyday life, the exhibition is organized around five main themes: material goods, food, ideas, landscapes, and people. When visitors walk through the galleries, they may be surprised to recognize themselves in aspects of the colonial capitol.

“Archaeology provides a tangible connection to the past through the materials we find,” said Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s executive director of archaeology. “These aren’t abstract ideas but materials that we can all look at together and that can spark discussions about our shared past. Guests will likely see themselves and the modern world in many of these themes.”

Wetherburn’s Tavern in Colonial Williamsburg was especially successful in the 1750s. The exhibition will include cowrie shells and a leaded glass Madeira decanter excavated at the site.

Among the highlighted objects are cowrie shells recovered from Wetherburn’s Tavern. Cowries are the small shells of marine gastropods that make their homes in shallow reef lagoons within the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Harvested in these regions, the shells of these creatures were used as currency throughout the Indo- Pacific and portions of sub-Saharan Africa for centuries, traveling from as far east as the Maldives to the Bight of Benin in western Africa. The value of these shells as money, however, led to their exploitation in the transatlantic slave trade. Purchased and processed in the Pacific, these shells were imported to West Africa by European traders extensively as goods of exchange to fund the forced migration of millions of Africans to the Americas. While these objects played a role in this story of human bondage and suffering, they may also speak to the power of memory and the resilient identity of those who were enslaved. Often recovered from archaeological sites once occupied by enslaved men, women, and children, these shells were also used as items of adornment or keepsakes. This kind of usage may speak to individuals’ attempts to draw on transatlantic memories and traditions to reclaim their identity in the face of the dehumanizing system of enslavement in the 18th century in places such as Williamsburg.

“Whether in the 18th century or today, the objects we use in our daily lives make statements about who we are, what we value, and the connections between ourselves and others in the world. It is exciting to bring so many artifacts that represent a truly diverse set of 18th-century Williamsburg’s population into the public eye,” said Sean Devlin, senior curator of archaeological collections at Colonial Williamsburg.

Another highlighted object to be seen in the exhibition is a fragment of a Chinese export porcelain platter owned by John Murry, Earl of Dunmore, who was the last royal governor of Virginia. It is especially unique as it may have traveled the farthest among the objects included in Worlds Collide. Adorned with the armorial decoration of a Scottish noble, this object was found among the late 18th-century refuse in Williamsburg on the site of Prentis Store. Most likely its story began as part of a written order for a large dinner service of tableware, perhaps accompanied by a drawing of the decoration, issued to a European merchant by Lord Dunmore. The order would have traveled to the Chinese port of Guangzhou where workshops specialized in applying the fine overglaze decoration that was requested. The porcelain pieces themselves, however, had previously been shipped to Guangzhou from the city of Jingdezhen (located 400 miles inland), which was an early factory city that produced nearly all porcelain for both domestic and export markets. Finally translated from text to physical object, this service was packed into the hold of a returning merchant ship before being delivered to Dunmore in Scotland. It then continued its global trek when Dunmore was appointed to governing positions first in New York and then Virginia. On the eve of the Revolution in 1775, Dunmore was forced to flee Williamsburg and left most of the family’s household possessions in the Governor’s Palace. From there, portions of this dinner service, which had literally sailed across most of the globe, ended their journey dispersed about the town.

Excavation at Wetherburn’s Tavern also produced a glass decanter for Madeira wine. In the 18th century, Virginians preferred to drink European wines at home and in taverns, and wines from Spain and Portugal were more prevalent than those from France. Among the favorites of Colonials was Madeira, a sweet, fortified wine produced on the Atlantic Island of the same name that was controlled by Portugal. Most of these wines were shipped in barrels or storage jars, and often needed to be decanted into individual bottles or vessels for serving. In this instance, not only did the contents of the decanter cross the world’s oceans but so did the vessel. Made of leaded glass, the decanter almost certainly was imported to Williamsburg upon a merchant ship from Britain and was of a very fashionable type in the mid-1700s. The body is engraved with a chain on which hangs a label bearing the engraved word ‘MADEIRA’ and surrounded by appropriate decoration, such as grapes, grape leaves, tendrils, and possibly grape flowers.

A broad hoe found at Carters Grove Plantation is an example of the agricultural products that flowed back and forth from the Virginia colony and Britain. Tobacco was the first crop to overtake the countryside in the areas around Williamsburg in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and the tendrils of this crop reached into every facet of daily life there. The tobacco hoe was a uniquely colonial tool that evolved over the 18th century as did the cultivation of the crop itself; the shape and construction of hoes changed in response to the needs of the agricultural enterprise. By early in the century, hoes were being produced in the tens of thousands in Britain for export to the colonies in North America and the Caribbean. This hoe is stamped with a repeated ‘AD’ mark that likely denoted the shop or individual who made the tool, even though their name is lost to time.

Further exemplifying how the 18th-century economy was truly global is a Tuscan oil jar found at the Anthony Hay House and Cabinet Shop site. Massive jars such as this were produced in northern Italy, particularly in the upper reaches of the Arno River Valley. The jars were brought down river and used to store and ship edible oils from ports such as Livorno. Among the largest buyers of these oils were British merchants and the

British navy. These pots traveled from Italian ports to docksides in London and around the globe in the holds of these ships, being found in such diverse settings as Jamaica, Patagonia, and coastal Australia, as well as Williamsburg.

For anyone fascinated by archaeology, globalization or material culture, Worlds Collide: Archaeology and Global Trade in Williamsburg is certain to fascinate, delight, and educate. It also will serve as an important orientation to Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area, as it will expand the visitor’s imagination to the daily lives of all those who lived there in the 18th century.

The exhibition is generously funded by Jacomien Mars.

Information on additional objects can be found here»

Exhibition | Looking Allowed?

Now on view at Ambras Castle in Austria:

Looking Allowed? Diversity from the 16th to the 18th Century

Schloss Ambras, Innsbruck, 20 June — 6 October 2024

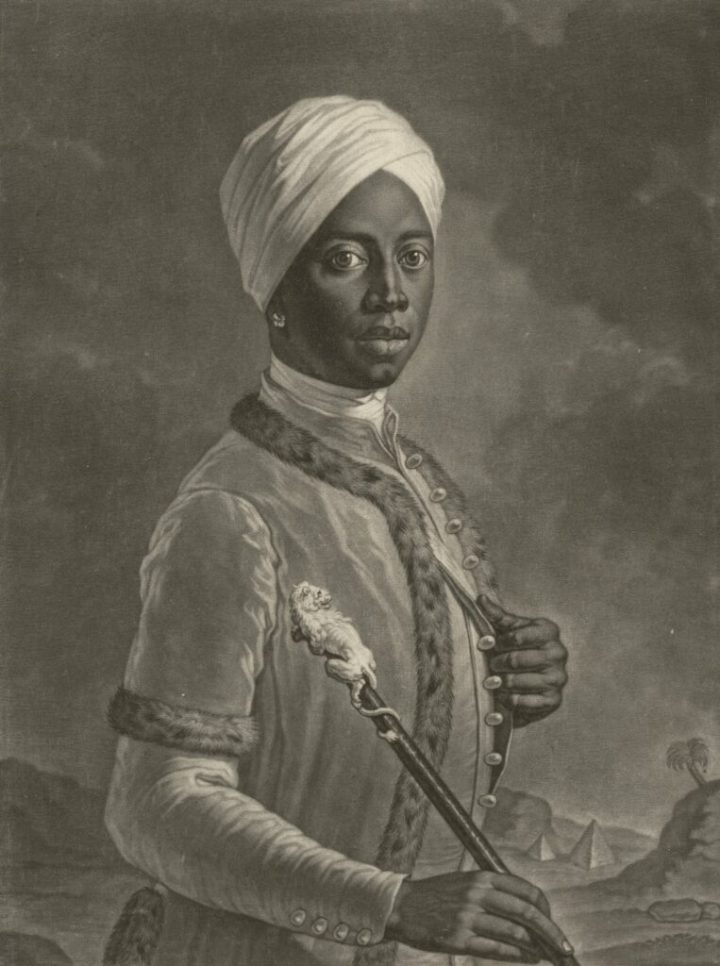

Johann Gottfried Haid after Johann Nepomuk Steiner, Portrait of Angelo Soliman (Mmadi Make), ca. 1750. Born in West Africa, Soliman was enslaved and shipped to Europe before eventually advancing in Austrian society as a successful Freemason and member of court.

Diversity has always existed. In the Renaissance—as humans increasingly took centre stage—it was not only the ideal that was of interest, but also humans’ inexhaustible diversity. The exhibition Looking Allowed? Human Diversity from the 16th to the 18th Century considers diversity in the past from today’s perspective, taking as its point of reference the Ambras collections of Archduke Ferdinand II. Here the whole world was illustrated, as was common in chambers of art and wonders.

Why did the Portrait of a Disabled Man find its way into the Ambras Chamber of Art and Wonders? Who is behind the ‘hair family’? And why do portraits of ‘court giants’ and ‘court dwarves’ move us? Such paintings run the risk of being dismissed as mere curiosities. This exhibition, by contrast, tells the stories of these people who did not fit period norms, taking as its theme the questions of whether, and if so, how encounters with them took place. It invites visitors to reflect on their own perceptions, confronting us with the question: ‘is it permissible to look?’

Current viewpoints are brought into the exhibition through audio and video contributions. Adapted font sizes and objects placed on different levels are aimed at reducing barriers and making it possible for a variety of visitors to experience the exhibition. Furthermore, the installation of a lift in the upper castle offers easy access for the first time to the special exhibition rooms located on the second floor.

Thomas Kuster, Christian Mürner, and Veronika Sandbichler, eds., Schauen erlaubt: Vielfalt Mensch vom 16. bis 18. Jahrhundert (Cologne: Walther König, 2024), 192 pages, ISBN: 978-3753306506, €19. With contributions by Volker Schönwiese, Katharina Seidl, Susanne Hehenberger, Eva Seemann, Anne Kuhlmann-Smirnov, and Rudi Risatti.

With statements, six essays, and over 70 catalog entries, the volume engages human diversity and the tensions between self-empowerment, acceptance, and discrimination.

Exhibition | Paris through the Eyes of Saint-Aubin

Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, Trade Card for Périer, Ironmonger, 1767, black chalk, pen and black and brown inks, brush and gray and brown wash

(New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Promised Gift of Stephen Geiger)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Opening in September at The Met:

Paris through the Eyes of Saint-Aubin

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 26 September 2024 — 4 February 2025

Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1724–1780) was a prolific and unconventional draftsman whose drawings invite viewers into every corner of the French capital. As an observer and chronicler, he prowled the streets of Paris and recorded the full spectrum of daily life in his sketchbooks, from shop interiors to art auctions and public gardens to rowdy street fairs. Everything he saw was worthy of his attention, wit, and empathy.

Saint-Aubin’s body of work is made up almost entirely of tiny, portable, and intricate works on paper. Taken together, these countless sketches give rise to a deeper view of the city as an organic form. Beyond capturing the tangible, they bring to light the pride and aspirations of Paris in the 18th century, a time when sites were being destroyed, rebuilt, and reimagined.

Marking the 300th anniversary of his birth, the exhibition features a thematic arrangement demonstrating the breadth of Saint-Aubin’s interests. Examples of his drawings and prints, drawn from The Met’s holdings and local private collections, are complemented by a selection of works by his family and contemporaries, offering a context for his career and highlighting the unique nature of his vision.

Exhibition | Imagination in the Age of Reason

Jean-Étienne Liotard, Portrait of François Tronchin, 1757, pastel on parchment; unframed: 38 × 46 cm

(The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978.54)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Opening this fall at The Cleveland Museum of Art:

Imagination in the Age of Reason

The Cleveland Museum of Art, 28 September 2024 — 2 March 2025

Although the Enlightenment period in Europe (about 1685–1815) has long been celebrated as ‘the age of reason’, it was also a time of imagination when artists across Europe incorporated elements of fantasy and folly into their work in creative new ways. Imagination in the Age of Reason, pulled from the CMA’s rich holdings of 18th-century European prints and drawings, explores the complex relationship between imagination and the Enlightenment’s ideals of truth and knowledge. During this unprecedented time, artists used their imaginations in multifaceted ways to depict, understand, and critique the world around them.

The Enlightenment adopted a revolutionary emphasis on individual liberty, direct observation, and rational thought. Enlightenment society valued learning and innovation, encouraging an unprecedented flowering of knowledge with major advances in fields as diverse as art, philosophy, politics, and science. Important thinkers of the time questioned long-held beliefs, instead using scientific reasoning to uncover new, objective principles on which to base a modern society, free from superstition, passion, and prejudice.

Filippo Morghen, Pumpkins Used as Dwellings To Be Secure against Wild Beasts, 1766–67, etching, image and plate: 28 × 39 cm (The Cleveland Museum of Art, 2023.19.8).

During this same period, a number of artists reveled in the power of the imagination to expose hidden truths, conjure strange worlds, or concoct illusions. François Boucher and Francisco de Goya, among others, drew on their imaginations to devise novel compositions, envision far-off places and people, attract new buyers for their art, and comment on society and its values. They also blurred the boundaries of fact and fantasy, incorporating real and invented elements into their compositions, often without distinguishing between the two. Imagination was a dynamic tool through which Enlightenment-era artists marketed their work, revealed or obscured truth, entertained or educated viewers, and supported or criticized systems of power.

The exhibition presents an exceptional opportunity to see exciting recent acquisitions on view for the first time as well as rarely shown collection highlights, including prints and drawings by Canaletto and Goya and a pastel portrait by Swiss artist Jean-Étienne Liotard.

Exhibition | Bologna during the Enlightnement

Now on view the Fesch Museum:

Bologne au siècle des Lumières: Art et science, entre réalité et théâtre

Palais Fesch, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Ajaccio, Corsica, 29 June — 30 September 2024

Attributed to Giacomo Boni, The Triumph of David, oil on canvas (Ajaccio, Palais Fesch, Musée des Beaux-Arts, 852.1.967).

Cette nouvelle exposition sur la peinture, la sculpture et les objets de curiosité, faite en collaboration avec la Pinacoteca Nazionale, les Musei Civici et la fondation de la Cassa di Risparmio de Bologne (CARISBO), s’inscrit dans le prolongement des précédentes expositions du musée d’Ajaccio portant sur l’art italien des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. Si le XVIIe siècle bolonais, celui des Carracci, de Reni et de Guercino, est bien connu en France, l’exposition permettra au public de découvrir une période moins familière de ce centre artistique.

Le XVIIIe siècle bolonais s’ouvre avec la fondation de l’Istituto delle Scienze et de l’Accademia Clementina, nés de la volonté du général Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, avec le soutien d’intellectuels inspirés des Lumières et l’approbation du Sénat. Les deux institutions bénéficient de la protection du pape Clément XI, le souverain qui a fait rentrer la ville dans le giron des États de l’Église.

Tandis que l’Istituto delle Scienze, réglé sur les dernières avancées scientifiques européennes, se propose de rendre son prestige à la cité, siège de la plus ancienne université, l’Accademia Clementina vise à retrouver les fastes du siècle d’or de la peinture célébré par la Felsina pittrice de Carlo Cesare Malvasia (1678) et lié aux noms des Carracci, de Reni et de Guercino. Le siècle naissant voit s’achever les carrières de peintres tels que le néo-carracesque Domenico Maria Viani, Benedetto Gennari, neveu de Guercino, rentré à Bologne après un long séjour en Angleterre, Giovanni Gioseffo dal Sole, dernier interprète des finesses de Guido Reni, et Carlo Cignani, prince à vie de l’Accademia Clementina, représentant d’un classicisme teinté de souvenirs corrégiens.

Dans la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle, l’opposition entre les deux champions de la peinture, Donato Creti et Giuseppe Maria Crespi, est radicale et irréductible. Les recherches du premier aboutissent à un classicisme élégant et raffiné, lumineux et incorruptible, alors que le second affiche au contraire un naturalisme agressif et prosaïque aux accents ironiques, d’un caractère presque populaire. Dans le même temps, la culture littéraire de l’Arcadia inspire, avec Marcantonio Franceschini, peintre européen cher aux princes de Liechtenstein, un purisme qui évolue vers un barocchetto atténué, habile et léger, apprécié des milieux aristocratiques et de l’autorité religieuse. Si les solennels tableaux d’autels répondent aux exigences du décorum et de la commande officielle, les grandes peintures destinées aux palais visent à célébrer, avec des allégories et l’évocation des gloires antiques, les familles sénatoriales, soutiens de l’autorité pontificale dans le gouvernement de la ville.

La ville pullule de petites comme de grandes collections. Ce sont non seulement les palais de l’aristocratie, mais aussi les habitations de la bourgeoisie ou des artisans qui se couvrent de peintures, disposées sous les fresques où se déploie la virtuosité perspective des peintres de quadratura.

Trompe-l’œil, dilatations spatiales et illusions théâtrales allant jusqu’à l’invraisemblable rendent les scénographes bolonais célèbres dans les théâtres européens, grâce aux succès de la famille Bibiena, dans le sillage des expériences passées d’Angelo Michele Colonna et d’Agostino Mitelli, appelés, au-delà des cours italiennes, jusqu’en Espagne et en France. Autour de l’Accademia Filarmonica, fréquentée entre autres par des personnalités telles que le chanteur Carlo Broschi, dit Farinelli, le compositeur Johan Christian Bach, le musicologue Charles Burney—à laquelle se sont joints des chanteurs, des compositeurs et des instrumentistes, sous l’œil attentif du célèbre père Giambattista Martini, qui fut le maître du Mozart lorsque celui-ci avait quatorze ans—se développe une intense activité mêlant architecture, peinture, musique et poésie, tandis qu’est inauguré en 1763 le Teatro Comunale avec le Triomphe de Clelia de Christoph Willibald Gluck, sur des textes de Métastase.

Une peinture légère opère la mutation de la solide tradition du XVIIe siècle vers le rocaille. Ses interprètes sont Francesco Monti, Giuseppe Marchesi dit Sanson, Vittorio Maria Bigari, Giuseppe Varotti et Nicola Bertuzzi, rejoints, en parfaite harmonie, par les sculpteurs et modeleurs Giovan Battista Bolognini, Francesco Jannsens, Angelo Piò et son fils Domenico, qui, à partir de l’exemple de Giuseppe Maria Mazza, donnent aux figures de stuc et de terre cuite un élégant mouvement tout en courbes et une grâce pleine de séduction.

Le succès de l’Accademia Clementina, dû au zèle de son secrétaire Gianpietro Zanotti, amène le remplacement progressif de la formation traditionnelle au sein des ateliers par des enseignements codifiés, l’institution officielle de prix dans les différentes branches artistiques et l’ouverture de l’Accademia del nudo. Dans ce contexte vont émerger les deux principales personnalités de la seconde moitié du siècle, les frères Ubaldo et Gaetano Gandolfi, chez qui la tradition s’est régénérée au contact fructueux de la culture picturale vénitienne, freinant l’avancée du néoclassicisme.

En 1796, à l’arrivée des troupes napoléoniennes, Gaetano Gandolfi pourra assister à l’effondrement de l’Ancien Régime, et aux bouleversements socio-politiques qui vont en découler : le renversement du pouvoir pontifical, la suppression des ordres religieux et des confréries laïques avec la confiscation de leurs biens. En remplacement de l’Accademia Clementina, la création de l’Accademia di Belle Arti, accompagnée de la naissance de la moderne Pinacoteca, inaugure cette nouvelle ère.

Bologne au siècle des Lumières: Art et science, entre réalité et théâtre (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2024), 368 pages, ISBN: 978-8836658527, €33.

leave a comment