Call for Articles | Sequitur (Fall 2025): Currents

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the Call for Papers:

Sequitur, Fall 2025 | Currents

Submissions due by 26 September 2025

The editors of SEQUITUR, the graduate student journal published by the Department of History of Art & Architecture at Boston University, invite current and recent MA, MFA, and PhD students to submit content on the theme of “Currents” for our Fall 2025 issue.

This issue invites submissions that consider how artistic activity and material culture make visible, help detect, and even resist the invisible forces at work in our world. When used in the scientific fields of meteorology or hydrology, currents describe the perpetual motion of air and water. In the study of the humanities, the term might connote a prevailing trend or the zeitgeist of a particular historical moment.

Furthermore, scholarship in the blue humanities frames oceanic and cultural currents as part of an assemblage, suggesting that the ocean’s liquid perpetual motion and heterogeneous material composition are more than just a backdrop for human culture. At its surface, the ocean has served as a site of imperial conquest, extractivism, and militarization, but is also a site of migration, diaspora, and resistance. Scholars Kimberley Peters and Philip Steinberg even use the concept of the ocean, and all that it intermingles with, as a “Hypersea” to describe how the ocean exceeds its liquid form, perpetual cycles, or a specific body of water by permeating and shaping physical matter, such as the atmosphere and our bodies, but especially our imaginations. Peters and Steinberg’s work provokes further consideration of what art historical scholarship might look like when informed by natural and social currents that exceed their boundaries and inscribe one another.

From 17th-century Dutch still life painters’ fascination with the products of colonial and transoceanic trade to contemporary work such as Hito Stereyl’s Liquidity Inc. (2014), which draws parallels between liquid currents and the fluidity of financial assets, identities, and borders in a digital world, artists, architects, and collectors have responded to the questions and conditions shaped by natural and social currents. This issue seeks to collect scholarship spanning antiquity to the present that grapples with such currents as complex, historical assemblages and asks where art might serve as a tool to interrogate them.

Possible subjects may include, but are not limited to:

• Currents, Movement, and Temporality: Flow; perpetual motion; flux; swell; direction; circulation; pushing and pulling; present; contemporary; prevailing; instant; prediction; ongoing; trends

• Currents and Systems: Weather patterns; transoceanic drift; mapping; hydrocommons; oceanic and atmospheric ecologies; rivers; oceans

• Currents and Culture: (Un)intended distribution (shells, marine salvage, etc.); spirituality and religion (ritual, baptism, purification, etc.); contact zones; migration; undercurrents

• Currents and Scholarship within the Oceanic Turn: transoceanic imaginaries (Elizabeth DeLoughrey); a “poetics of planetary water” (Steve Mentz); tidalectics (Kamau Brathwaite); the Undersea, and other theoretical methods (including works of Stacy Alaimo, Hester Blum, John R. Gillis, Epeli Hau’ofa, Melody Jue, Astrida Neimanis, Serpil Oppermann, or Philip Steinberg, among many others)

SEQUITUR welcomes submissions from graduate students in the disciplines of art history, architecture, archaeology, fine arts, material culture, visual culture, literary studies, queer and gender studies, disability studies, memory studies, and environmental studies, among others. We encourage submissions that take advantage of the digital format of the journal.

Founded in 2014, SEQUITUR is an online biannual scholarly journal dedicated to addressing events, issues, and ideas in art and architectural history. SEQUITUR, edited by graduate students at Boston University, engages with and expands current conversations in the field by promoting the perspectives of graduate students from around the world. It seeks to contribute to existing scholarship by focusing on valuable but often overlooked parts of art and architectural history. Previous issues of SEQUITUR can be found here.

We invite full submissions in the following categories. Please submit your material in full for consideration in the publication:

Feature essays (1,500 words)

Content should present original material that falls within the stipulated word limit (1,500 words). Please adhere to the formatting guidelines available here.

Visual and creative essays (250 words, up to 10 works)

We invite M.Arch. or M.F.A. students to showcase a selection of original work in or reproduced in a digital format. We welcome various kinds of creative projects that take advantage of the online format of the journal, such as works that include sound or video. Submissions should consist of a 250-word artist statement and up to 10 works in JPEG, HTML, or MP4 format. All image submissions must be numbered and captioned and should be of good quality and high resolution.

We invite proposals for the following categories. Please write an abstract of no more than 200 words outlining your intended project:

Exhibition reviews (500 words)

We are especially interested in exhibitions currently on display or very recently closed. We typically prioritize reviews of exhibitions in the Massachusetts and New England area.

Book or exhibition catalog reviews (500 words)

We are especially interested in reviews of recently published (1–3 years old) books and catalogs.

Interviews (750 words)

Please include documentation of the interviewee’s affirmation that they will participate in an interview with you. Plan to provide either a full written transcript or a recording of the interview (video or audio).

Research spotlights (750 words)

Short summaries of ongoing research written in a more casual format than a feature essay or formal paper. For research spotlights, we typically, but not universally, prioritize doctoral candidates who plan to use this platform to share ongoing dissertation research or work of a comparable scale.

To submit, please send the following materials to sequitur@bu.edu:

• Your proposal or submission

• A recent CV

• A brief (50-word) bio

• Your contact information in the body of the email: name, institution, program, year in program, and email address

• ‘SEQUITUR Fall 2025’ and the type of submission/proposal as the subject line

All submissions and proposals are due 26 September 2025. Please remember to adhere to the formatting guidelines available here. Text must be in the form of a Word document, and images should be sent as .jpeg files. While we welcome as many images as possible, at least one must be very high resolution and large format. All other creative media should be sent as weblinks, HTML, or MP4 files if submitting video or other multimedia work. Please note that authors are responsible for obtaining all image copyright releases before publication. Authors will be notified of the acceptance of their submission or proposal the week of 15 October 2025, for publication in January 2026. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact the SEQUITUR editors at sequitur@bu.edu.

The SEQUITUR Editorial Team

Ada, Emma, Hamin, Isabella, Jenna and Megan

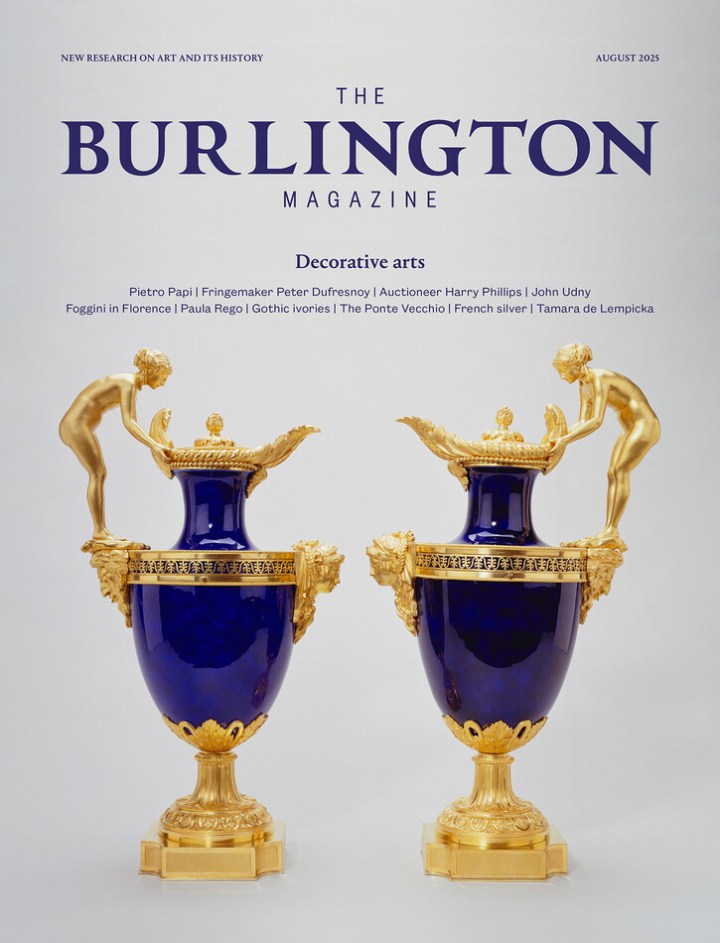

The Burlington Magazine, August 2025

The long 18th century in the August issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 167 (August 2025) | Decorative Arts

e d i t o r i a l

• Studying the Decorative Arts, p. 755.

• Studying the Decorative Arts, p. 755.

The serious study of the decorative arts and the pleasures that derive from it have been an important feature of The Burlington Magazine since the early twentieth century. But how healthy is this field of research today? Arguably, it remains a specialised endeavour rather than holding a very prominent place in the mainstream of art-historical studies; and although there are some brilliant advocates for it and encouraging developments, an uncertain future is the key concern, as is the case with so many areas of scholarship in universities, museums and the market.

l e t t e r

• Philip McEvansoneya, “Lefèvre in Ireland,” pp. 756–57. Response to Humphrey Wine’s article in the May issue, “Napoleon Crossing the Alps: British Press Reaction to the London Exhibitions of David, Lefèvre, Wicar, and Lethière,” pp. 450–59.

a r t i c l e s

• Annabel Westman, “Peter Dufresnoy, Fringe and Lacemaker Extraordinaire,” pp. 758–75.

The French fringe and lacemaker Peter Dufresnoy excelled at his craft and trade in Restoration London. A close study of written sources and surviving works by him facilitates a reconstruction of his brilliant career. His patrons included the Duke of Lauderdale (Ham House), Mary Howard, Duchess of Norfolk and 7th Baroness Mordaunt (Drayton House), the Earl of Exeter (Burghley House) and the Dowager Queen Catherine of Braganza.

Roll-top desk. France, ca.1790, mounted with 16th-century Japanese lacquer, wood, black lacquer, gold and silver lacquer, mother of pearl, leather and gilt metal mounts, 110 × 95 × 55 cm (Royal Collection Trust; © His Majesty King Charles III 2025). The desk was acquired by the Prince of Wales (the future George IV) from Harry Phillips.

• Helen Jacobsen, “Harry Phillips and the Development of the London Decorative Art Market, 1796–1839,” pp. 776–91.

Analysis of sale catalogues assists in an assessment of the career of Harry Phillips, the least known of London’s significant Regency auctioneers. He specialised in decorative arts sales and his clients included William Beckford, the Prince of Wales and the Earl of Yarmouth. Notable works acquired at his auctions are now in the Royal Collection and the Wallace Collection, London.

• Brendan Cassidy, “John Udny and the ‘Battle of Pavia’ Tapestries, 1762–74,” pp. 792–99.

To commemorate Emperor Charles V’s victory at the Battle of Pavia in 1525, a set of seven tapestries illustrating key moments in the conflict were presented to the emperor by the Netherlands in 1531. They are now in the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, and their provenance between 1762 and 1774 is established here by connecting them to John Udny, a Scottish diplomat, art collector and dealer.

• Romana Mastrella, “Two Monumental Maiolica Amphoraefrom the Papi Workshop: New Insights and Contexts,” pp. 800–05.

Recently acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, two large ‘istoriato’ maiolica vases [1670] featuring scenes from Torquato Tasso’s poem ‘Gerusalemme Liberata’ illustrate the continued presence of pottery workshops in seventeenth-century Urbania. Two previously unpublished documents help to contextualise their maker, Pietro Papi, as well the Papi family workshop, within the social and economic dynamics of central Italian ceramic production.

r e v i e w s

• Christopher Baker, “New Collection Displays at the National Gallery, London,” pp. 806–15.

• Christopher Baker, “New Collection Displays at the National Gallery, London,” pp. 806–15.

In May 2025, as the final part of its bicentenary celebrations, the National Gallery, London, unveiled extensive new displays of its paintings. Juxtaposing the familiar and the unexpected, they provide fresh perspectives on its outstanding and expanding collection.

• David Pullins, Review of the newly renovated Frick Collection in New York, pp. 816–19.

• Nicola Ciarlo, Review of the exhibition Giovan Battista Foggini: Architetto e scultore granducale (Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence), pp. 824–27.

• Charles Saumarez Smith, Review of the new V&A East Storehouse in London, pp. 837–39.

• Kirstin Kennedy, Review of Peter Fuhring, The French Silverware in the Calouste Gulbenkian Collection (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 2023); and Charissa Bremer-David, with contributions by Jessica Chasen, Arlen Heginbotham, and Julie Wolfe, French Silver in the J. Paul Getty Museum (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2023), pp. 840–42.

• Humphrey Wine, Review of Nicolas Lesur, Pierre Subleyras (1699–1749) (Arthena, 2023), pp. 848–49.

• Françoise Barbe, Review of Marco Spallanzani, Otto studi sul vetro a Firenze, Secoli XIV–XVIII (Edifir Edizioni, 2024), pp. 849–50.

• Marika Sardar, Review of Sonal Khullar, ed., Old Stacks, New Leaves: The Arts of the Book in South Asia (University of Washington Press, 2023), 850–51.

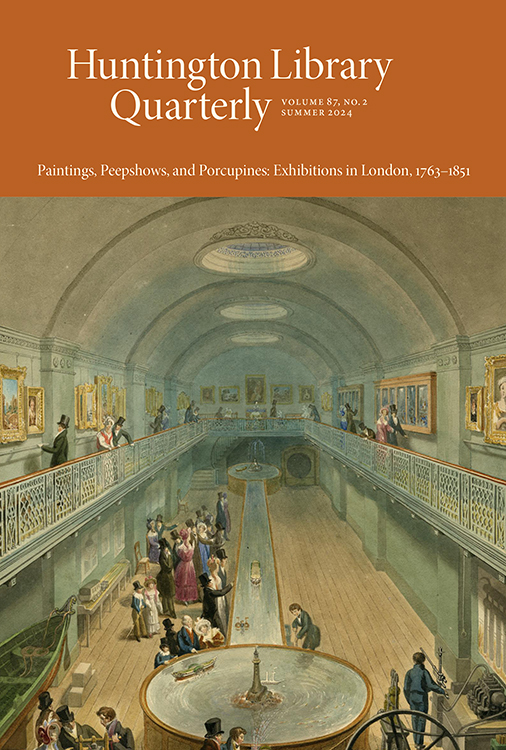

Huntington Library Quarterly, Summer 2024 | Exhibitions in London

This special issue of HLQ arises from a conference held at the Huntington Library in September 2023:

Huntington Library Quarterly 87.2 (Summer 2024)

Paintings, Peepshows, and Porcupines: Exhibitions in London, 1763–1851

Edited by Jordan Bear and Catherine Roach

Dazzling variety characterized exhibitions in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain: boxing matches, automata, contemporary art shows, panoramas, dog beauty contests, and menageries all contributed to a flourishing display culture. Despite their differences, these attractions shared both techniques for engaging audiences and widely reverberating themes. All of the essays in this volume work across multiple sites of display. By examining the varied terrain of exhibitions collectively, this issue illuminates cultural preoccupations of the time, including the multifarious impact of empire and the productively ambiguous boundaries between the cultural expressions that were deemed low and those that were deemed high.

Dazzling variety characterized exhibitions in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain: boxing matches, automata, contemporary art shows, panoramas, dog beauty contests, and menageries all contributed to a flourishing display culture. Despite their differences, these attractions shared both techniques for engaging audiences and widely reverberating themes. All of the essays in this volume work across multiple sites of display. By examining the varied terrain of exhibitions collectively, this issue illuminates cultural preoccupations of the time, including the multifarious impact of empire and the productively ambiguous boundaries between the cultural expressions that were deemed low and those that were deemed high.

c o n t e n t s

• Jordan Bear and Catherine Roach, “Introduction: Exhibitions in London, 1763–1851,” pp. 153–63.

• Adam Eaker, “The Art of Marring a Face: Exhibiting Boxers in Georgian London,” pp. 165–82.

• Nicholas Robbins, “The Circumference of the Subject: Figuring Race at Egyptian Hall,” pp. 183–205.

• Rosie Dias, “Making Space for Empire: India in Panoramas and Dioramas, 1830–1851,” pp. 207–31.

• Holly Shaffer, “Provisioners, Cooks, Coffeehouses, and Clubs: Exhibiting Taste in Calcutta and London in the Early Nineteenth Century,” pp. 233–54.

• Jordan Bear, “The Sea Serpent of Regent Street: On the Evidentiary Strategies of Nineteenth-Century Exhibitions,” pp. 255–71.

• Catherine Roach, “Dog Shows: Porcelain Pugs and Pre-Raphaelite Painters in Thomas Earl’s Art and Nature,” pp. 273–90.

• Alison FitzGerald, “Centers and Peripheries: Exhibiting London’s ‘Marvels’ in Britain’s ‘Second City’,” pp. 291–311.

• John Plunkett, “An Early Moving Picture Industry? Exhibition Networks and the Panorama, 1810–1850,” pp. 313–35.

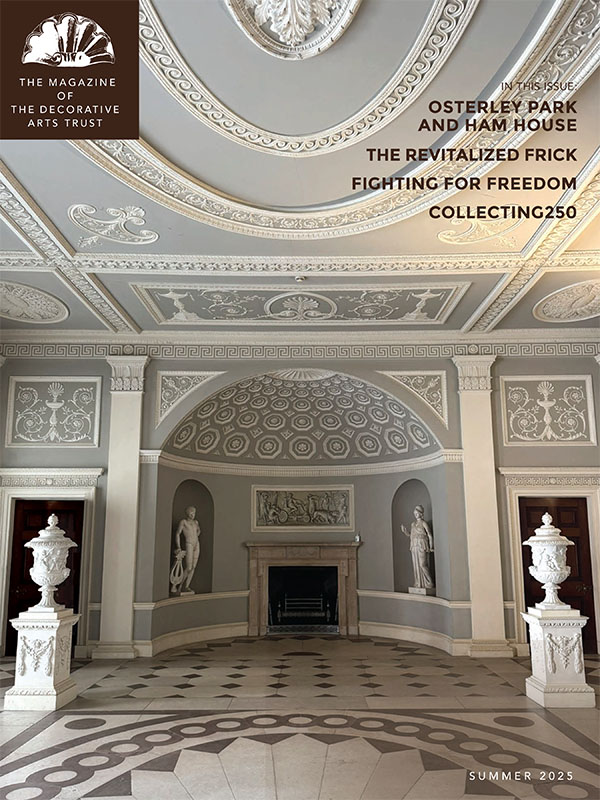

The Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust, Summer 2025

The Decorative Arts Trust has shared select articles from the summer issue of their member magazine as online articles for all to enjoy. The following articles are related to the 18th century:

The Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust, Summer 2025

• “Time Travel in the Thames Valley: Ham House and Osterley Park” by Megan Wheeler Link»

• “Time Travel in the Thames Valley: Ham House and Osterley Park” by Megan Wheeler Link»

• “Whose Revolution at the Concord Museum” by Reed Gochberg Link»

• “Fighting for Freedom: Black Craftspeople and the Pursuit of Independence” by William A. Strollo Link»

• “Decorative Arts Shine at the Reopened Frick” by Marie-Laure Buku Pongo Link»

• “A Room of Her Own: New Book Explores the Estrado” by Alexandra Frantischek Rodriguez-Jack Link»

• “Luster, Shimmer, and Polish: Transpacific Materialities in the Arts of Colonial Latin America” by Juliana Fagua Arias Link»

The printed Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust is mailed to Trust members twice per year. Additional membership information is available here.

Pictured: The magazine cover depicts the Entrance Hall at Osterley Park showcasing Robert Adam’s signature Neoclassical style. The apsidal end features plasterwork by Joseph Rose and contains statues of Apollo and Minerva. The marble urns are attributed to Joseph Wilton. Decorative Arts Trust members visited the house during the Thames Valley Study Trip Abroad tours in May and June 2025.

The Burlington Magazine, July 2025

The long 18th century in the July issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 167 (July 2025)

e d i t o r i a l

Maria van Oosterwijck, Vanitas stilleven, ca. 1675, oil on canvas (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum).

• “The Gallery of Honour,” p. 635. The gallery of honour in the heart of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, has recently welcomed an impressive painting to its walls: Vanitas still life by Maria van Oosterwijck (1630–93). In a compelling sense the artist has long had a place in galleries of honour, as works by her were acquired by Emperor Leopold I, Louis XIV of France, and Cosimo III de’ Medici of Tuscany.

r e v i e w s

• Christian Scholl, “Germany’s Celebration of Caspar David Friedrich’s 250th Anniversary,” pp. 694–701.

In Germany, the 250th anniversary of Caspar David Friedrich’s birth was celebrated with a series of exhibitions. Key among them were those organised by the three museums with the most extensive holdings of the artist’s work: the Hamburger Kunsthalle, the Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin, and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden. All three focused on stylistic, iconographic and technical aspects of the artist’s work rather than on Friedrich’s life, and each in its own way has thrown fresh light on his complex and enigmatic art.

Luis Egidio Meléndez, Still Life with Figs, ca. 1760, oil on canvas (Paris: Musée du Louvre, on view at the Musée Goya, Castres).

• Robert Wenley, Review of the exhibition Wellington’s Dutch Masterpieces (Apsley House, London, 2025), pp. 713–15.

• Christoph Martin Vogtherr, Review of the exhibition Corot to Watteau? On the Trail of French Drawings (Kunsthalle Bremen, 2025), pp. 715–18.

• Elsa Espin, Review of the exhibition Le Louvre s’invite chez Goya (Musée Goya, Castres, 2025), pp. 718–20.

• John Marciari, Review of the exhibition Picturing Nature: The Stuart Collection of 18th- and 19th-Century British Landscapes and Beyond (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2025), pp. 720–22.

• Kee Il Choi Jr., Review of the exhibition Monstrous Beauty: A Feminist Revision of Chinoiserie (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, pp. 722–25.

• Deborah Howard, Review of Mario Piana, Costruire a Venezia: I mutamenti delle tecniche edificatorie lagunari tra Medioevo e Età moderna (Marsilio, 2024), pp. 732–33.

• Isabelle Mayer-Michalon, Review of Christophe Huchet de Quénetain and Moana Weil-Curiel, Étienne Barthélemy Garnier (1765–1849): De l’Académie royale à l’Institut de France (Éditions Faton, 2023), pp. 737–39.

Call for Submissions | Metropolitan Museum Journal

Metropolitan Museum Journal 61 (2026)

Submissions due by 15 September 2025

The Editorial Board of the peer-reviewed Metropolitan Museum Journal invites submissions of original research on works of art in the Museum’s collection. The Journal publishes Articles and Research Notes. Works of art from The Met collection should be central to the discussion. Articles contribute extensive and thoroughly argued scholarship—art historical, technical, and scientific—whereas Research Notes are narrower in scope, focusing on a specific aspect of new research or presenting a significant finding from technical analysis, for example. The maximum length for articles is 8,000 words (including endnotes) and 10–12 images, and for research notes 4,000 words (including endnotes) and 4–6 images. Articles and Research Notes in the Journal appear in print and online, and are accessible in JStor on the University of Chicago Press website.

The process of peer review is double-anonymous. Manuscripts are reviewed by the Journal Editorial Board, composed of members of the curatorial, conservation, and scientific departments, as well as scholars from the broader academic community. Submission guidelines are available here. Please send materials to journalsubmissions@metmuseum.org. The deadline for submissions for Volume 61 (2026) is 15 September 2025.

The Art of the Ephemeral in 18th-Century France

Paul-André Basset, Fête du 14 Juillet An IX, ca. 1801, hand-colored engraving, 28 × 44 cm (Paris: Bibliothèque de l’Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art). The print depicts the national holiday, as celebrated on the Champs-Élysées and organized by Chalgrin, commemorating the storming of the Bastille in 1789.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

All contents from this special issue of Status Quaestionis are available as free downloads:

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow?

The Art of the Ephemeral in Eighteenth-Century France

Status Quaestionis: Language, Text, Culture 28 (2025)

Edited by Elisa Cazzato

This monographic issue of Status Quaestionis explores the notion of ephemerality in French artistic culture during the long eighteenth-century. The volume is highly interdisciplinary, featuring articles from art and theatre history, costume-making, and performance studies, extending the notion of the ephemeral to a wide range of examples. The authors investigate how, in order to exist, ephemerality needs materiality, since any creative process intersects with the material requirement that both artworks and performances need: materials, locations, settings, scripts, costumes, and bodies. This dichotomy enables historians to further analyse the cultural and political meanings of the ephemeral, connecting artworks to social contexts, dance costumes to movements, and public festivals to human reception. Rather than focusing solely on aesthetics, the volume interrogates how the ephemeral was experienced, recorded, and remembered and how its traces persist in artworks, texts, and collective memory. The contributions question the boundary between presence and absence, visibility and oblivion, reflecting on the long-term cultural implications of transience. In seeking what remains of the ephemeral, the volume challenges dominant narratives and reconsiders the politics of cultural memory.

This special issue was inspired by the intellectual discussions that took place during the international conference organised at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in June 2023. The conference was part of the research project SPECTACLE, funded by the European Union’s Horizion 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 893106.

t h e m a t i c a r t i c l e s

Jean-Baptiste-Philibert Moitte, The Comte d’Artois as a Hunter, ca. 1777, gouache on paper, 22.9 × 30 cm (Amiens, Musée de Picardie). Figure 1 from the article by Noémie Étienne and Meredith Martin.

• Introduction: Here Today, Gone Tomorrow? The Art of the Ephemeral in Eighteenth-Century France — Elisa Cazzato

• ‘Mais, le lendemain matin’: Residues of the Ephemeral in Eighteenth-Century French Art — Mark Ledbury

• Spectacular Blindness: Enslaved Children and African Artifacts in Eighteenth-Century Paris — Noémie Étienne and Meredith Martin

• L’art du comédien au tournant des Lumières: Conscience de l’éphémère et sensibilité mémorielle — Ilaria Lepore

• L’expérience éphémère d’Ériphyle (Voltaire, 1732): Matériaux tangibles et réécritures d’une dramaturgie passagère — Renaud Bret-Vitoz

• Un événement unique: Le théâtre de la Révolution entre surgissement et disparition — Pierre Frantz

• Ephemeral Emblem: Jacques-Louis David and the Making of a Revolutionary Martyr — Daniella Berman

• Les feux d’artifices des frères Ruggieri à l’intérieur d’un théâtre: L’autonomie de l’éphémère dans le Paris du XVIIIe siècle — Emanuele De Luca

• Tra utopia e ricerca del consenso: Fuochi e apparati effimeri di epoca napoleonica a Milano tra il 1801 e il 1803 — Alessandra Mignatti

• Witnesses of the Past: Costumes as Material Evidence of the Ephemeral Performance — Petra Zeller Dotlačilová

• Noverre’s Lament: Inscription, Posterity, and the Ephemeral Art of Dance — Olivia Sabee

• Ephemerality on the Fringe: Exploring the Venues Hosting Power Quadrilles in Brussels on the Eve of Waterloo and Beyond (1814–1816) — Cornelis Vanistendael

Miscellaneous articles and reviews are available here»

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Elisa Cazzato is research fellow at the University of Naples Federico II. She holds a PhD in art history from the University of Sydney, and she is a former Marie Skłodowska-Curie Global Fellow. For her project SPECTACLE she was a visiting scholar at the CELLF of the Université Sorbonne and in the New York University’s Department of Art History. Her publications include articles in the peer-review journals Studi Francesi, Dance Research, Humanities Research Journal, and RIEF. She is currently writing her first book on the life and career of Ignazio Degotti.

Alixe Bovey Appointed Editor-in-Chief at British Art Studies

From the Paul Mellon Centre announcement (16 June 2025) . . .

Alixe Bovey has been appointed to the position of British Art Studies (BAS) Editor-in-Chief. In this role she will lead on the development of material for publication in the journal, commission new articles and projects, and work collaboratively with authors. BAS is an innovative space for new peer-reviewed scholarship on all aspects of British art, co-published by Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and the Yale Center for British Art.

Alixe Bovey has been appointed to the position of British Art Studies (BAS) Editor-in-Chief. In this role she will lead on the development of material for publication in the journal, commission new articles and projects, and work collaboratively with authors. BAS is an innovative space for new peer-reviewed scholarship on all aspects of British art, co-published by Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and the Yale Center for British Art.

Alixe is Professor of Medieval Art History at The Courtauld, where she specialises in the art and culture of the Middle Ages. Her particular interests include illuminated manuscripts, visual storytelling and the relationship between myth and material culture across historical periods and geographical boundaries. Her publications explore a variety of medieval and early Renaissance topics, including Gothic art and immateriality (2015), monsters (2002, 2013), English genealogical rolls (2005, 2021), and monographic studies including Jean de Carpentin’s Book of Hours (Paul Holberton Press, 2011). Following a ten-year stint as Head of Research then Executive Dean and Deputy Director of The Courtauld, she is currently at work on a new book exploring the vibrant culture of storytelling in word and image in fourteenth-century London. Alongside her historical research, she is keenly interested in the creative relationship between practice and art history, and has organised a variety of programmes that bring works of art, artists and art historians together.

Sarah Victoria Turner, Director of PMC, comments: “We are so excited to have Alixe leading British Art Studies and I know she will do this with huge curiosity and commitment to publishing original research on British art. She has been an advocate for the journal and our approach to digital publishing.”

Alixe took up the role in June 2025 with a tenure of two years. Researchers interested in publishing with BAS are warmly encouraged to contact Alixe with questions, ideas or manuscripts for submission at baseditor@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk.

The Burlington Magazine, June 2025

Francesco Guardi, Venice: The Rialto Bridge with the Palazzo dei Camerlenghi, ca.1764, oil on canvas, 120 × 204 cm

(Private collection)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The long 18th century in the June issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 167 (June 2025)

e d i t o r i a l

• “American Gothic,” p. 531.

There are many excoriating ways in which the current administration in Washington might be described; a number of them are perhaps too impolite to appear in a decorous journal such as this. The necessity of restraint does not, however, mean we should refrain from expressing a view on the provocative actions of the new United States government. They are not merely a matter of political theatre that feeds the news cycles, but also a corrosive force that is undermining many valued cultural institutions and having a direct and negative impact on the lives of tens of millions of people.

l e t t e r

• David Wilson, “More on Lorenzo Bartolini’s The Campbell Sisters Dancing a Waltz,” pp. 532–34.

Response to the article in the February issue by Lucy Wood and Timothy Stevens, “The Elder Sisters of The Campbell Sisters: William Gordon Cumming’s Patronage of Lorenzo Bartolini.”

a r t i c l e s

Joshua Reynolds, Elizabeth Percy, Countess (later Duchess) of Northumberland, 1757, oil on canvas, 240 × 148.6 cm. (Collection of the Duke of Northumberland, Syon House, London).

• Justus Lange and Martin Spies, “Two Royal Portraits by Reynolds Rediscovered in Kassel,” pp. 564–71.

Two paintings in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Kassel, are here identified as portraits by Joshua Reynolds of Princess Amelia, second daughter of George II, and her brother William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland. Both were gifts from the sitters to their sister Mary, Landgravine of Hesse-Kassel, a provenance that sheds new light on the cultural links between England and the landgraviate in the mid-eighteenth century.

• Giovanna Perini Folesani, “An Unpublished Letter by Sir Joshua Reynolds,” pp. 575–78.

in the historical archive of the Accademia di Belle Arti, Florence, there is an autograph letter by Sir Joshua Reynolds dated 20th May 1785 that was sent from London. . . . The text is in impeccable Italian, suggesting that Reynolds copied a translation made by a native speaker. . . .

• Francis Russell, “Guardi and the English Tourist: A Postscript,” pp. 578–83.

Some three decades ago this writer sought to demonstrate in this Magazine that the early evolution of Francesco Guardi (1712–93) as a vedutista could be followed in a number of pictures supplied to English patrons who were in Venice from the late 1750s. Other pieces of the jigsaw now fall into place. . . .

r e v i e w s

• Christoph Martin Vogtherr, Review of Schönbrunn: Die Kaiserliche Sommerresidenz, edited by Elfriede Iby and Anna Mader-Kratky (Kral Verlag, 2023), pp. 614–16.

• Steven Brindle, Review of Christopher Tadgell, Architecture in the Indian Subcontinent: From the Mauryas to the Mughals (Routledge, 2024), pp. 620–21.

• Stephen Lloyd, Review of ‘What Would You Like?’ Collecting Art for the Nation: An Account by a Director of Collections, edited by Magnus Olausson and Eva-Lena Karlsson (Nationalmuseum Stockholm, 2024), pp. 627–28.

Print Quarterly, June 2025

George Cuitt, Gateway at Denbigh Castle, 1813, etching, 252 × 315 mm

(London, British Museum), reproduced on p. 200.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

The long eighteenth century in the latest issue of Print Quarterly:

Print Quarterly 42.2 (June 2025)

a r t i c l e s

• Jane Eade, “A Mezzotint by Jacob Christoff Le Blon (1667–1741) at Oxburgh Hall,” pp. 143–53. This article examines a newly discovered impression of Jacob Christoff Le Blon’s colour mezzotint after Sir Anthony van Dyck’s (1599–1641) portrait of The Three Eldest Children of Charles I at Windsor Castle. The author discusses Le Blon’s invention of his revolutionary printing technique, the print’s distribution history, the operations of Le Blon’s workshop known as the ‘Picture Office’, as well as the circumstances surrounding the Oxburgh Hall impression, including its recent conservation treatment.

• Stephen Bann, “Abraham Raimbach and the Reception of Prints after Sir David Wilkie in France,” pp. 154–67. This article establishes the premise that Sir David Wilkie (1785–1841) introduced a new style of narrative painting in England that would prove influential for painting throughout Europe. It was previously thought that Paul Delaroche (1797–1856) popularized this new narrative style a couple of decades later in France. Since the French public had no local access to Wilkie’s paintings, it is here shown that it was the reproductive engravings of Abraham Raimbach that brought Wilkie to their attention. In doing so, this idea challenges the centrality of Delaroche’s sole influence on European painting.

• Paul Joannides, “John Linnell, Leonardo Cungi and the Vault of the Sistine Chapel,” pp. 168–84. This article discusses John Linnell’s (1792–1882) mezzotints after the Sistine Chapel ceiling and the recently discovered drawings on which the prints were based. The drawings, once a single sheet, are here attributed to Leonardo Cungi (1500/25–69); in its entirety, it is the earliest known copy to show the complete ceiling in full detail.

n o t e s a n d r e v i e w s

William Blake, Joseph of Arimathea among the Rocks of Albion, ca. 1773, engraving, 254 × 138 mm (Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum), reproduced on p. 192.

• Ulrike Eydinger, Review of Jürgen Müller, Lea Hagedorn, Giuseppe Peterlini and Frank Schmidt, eds., Gegenbilder. Bildparodistische Verfahren in der Frühen Neuzeit (Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021), pp. 185–87.

• Nigel Ip, Review of Owen Davies, Art of the Grimoire (Yale University Press, 2023), pp. 187–89.

• Antony Griffiths, Review of Mario Bevilacqua, ed., Edizione Nazionale dei Testi delle Opere di Giovanni Battista Piranesi. I. Opere giovanili, ‘Vedute di Roma’, ‘Pianta di Roma e Campo marzo’ (De Luca Editori d’Arte, 2023), pp. 191–92.

• Mark Crosby, John Barrett and Adam Lowe, Note on William Blake as an apprentice engraver, pp. 192–93.

• Ersy Contogouris, Review of Pascal Dupuy, ed. De la création à la confrontation. Diffusion et politique des images (1750–1848) (Presses Universitaires de Rouen et du Havre, 2023), pp. 194–95.

• Cynthia Roman, Review of David Atkinson and Steve Roud, Cheap Print and Street Literature of the Long Eighteenth Century (Open Book Publishers, 2023), pp. 197–98.

• Sarah Grant, Review of Peter Boughton and Ian Dunn, George Cuitt (1779–1854), ‘England’s Piranesi’: His Life and Work and a Catalogue Raisonné of His Etchings (University of Chester Press, 2022), pp. 199–201.

• Timon Screech, Review of Akiko Yano, ed., Salon Culture in Japan: Making Art, 1750–1900 (British Museum Press, 2024), pp. 201–03.

• Bethan Stevens, Review of Evanghelia Stead, Goethe’s Faust I Outlined: Moritz Retzsch’s Prints in Circulation (Brill, 2023), pp. 240–43.

leave a comment