The Burlington Magazine, August 2024

The long 18th century in the August issue of The Burlington—and special thanks to The Burlington for making Rosalind Savill’s article available to Enfilade readers for free.

The Burlington Magazine 166 (August 2024) — Decorative Arts

a r t i c l e s

Unidentified artist, Portrait of Paul Crespin, ca.1726, oil on canvas laid on board, 114 × 90 cm (London: Victoria and Albert Museum).

• Lucy Wood and Olivia Fryman, “The 1st Duke of Devonshire’s ‘Queen Mary’ Beds at Devonshire House, Chatsworth, and Hardwick Hall,” pp. 780–809.

In 1696 the 1st Duke of Devonshire purchased two beds that had belonged to Mary II, one of which was made by Louis XIV’s upholsterer, Simon Delobel. Documents and fragments of its crimson velvet embroidered hangings record a lost example of Stuart state furniture of the highest quality.

• Stefano Rinadli, “Six Horses for the King of Poland: Making and Staging a Diplomatic Gift at the Court of Louis XIV,” pp. 810–25.

In July 1715 Augustus the Strong of Saxony-Poland received a splendid present from the Sun King: a team of six Spanish stallions, each equipped with embroidered trappings and a pair of elaborate flintlock holster pistols. Documents published here for the first time help establish the gift’s political context and chronology and provide detailed insight into the payment and the identity of all the craftsmen involved.

• Teresa Leonor M. Vale, “Eighteenth-Century English Silver for King João V of Portugal,” pp. 826–33.

João V of Portugal acquired works of art from Rome and Paris; analysis of diplomatic correspondence illustrates how he also commissioned objects from Britain in the 1720s, notably spectacular examples of silverware. These included and exceptionally large and renowned silver-gilt bath by Paul Crespin, the Huguenot silversmith who lived and worked in Soho, London.

Detail of the bottom tray of worktable mounted with two trays, attributed to Bernard II van Risenburgh, ca.1761–63. Table: wood, green varnish and gilt-bronze mounts, 68.6 × 36.8 × 30.5 cm; trays: Sèvres soft-paste porcelain, green ground, enamel colours and gilding, 32 × 26 cm (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 58.75.45).

• Rosalind Savill, “From Storeroom to Stardom: The Revelations of Two Sèvres Porcelain Trays,” pp. 834–47.

Two porcelain trays set into a Rococo table in the early 1760s, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, are reassessed and here confirmed as Sèvres. Their subjects are probably the family of the Marquis de Courteille, Louis XV’s representative at the porcelain factory, and their intimate representation in this manner is almost unique in eighteenth-century Sèvres.

The full article is available for free here»

r e v i e w s

• Elizabeth Savage, Review of two exhibition catalogues: Edina Adam and Julian Brooks, with an essay by Matthew Hargraves, William Blake: Visionary (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2020); and David Bindman and Esther Chadwick, eds., William Blake’s Universe (Philip Wilson Publishers, 2024), pp. 862–65.

• John Pinto, Review of the exhibition catalogue, John Marciari, Sublime Ideas: Drawings by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Paul Holberton Publishing, 2023), pp. 865–67,

• Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Review of the exhibition catalogue, Rosario Inés Granados, ed., Painted Cloth: Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America (University of Texas Press, 2022), pp. 867–69.

• Camilla Pietrabissa, Review of the exhibition catalogue, Anita Viola Sganzerla and Stephanie Buck, eds., Connecting Worlds: Artists and Travel (Paul Holberton Publishing, 2023), pp. 870–72.

• Giullaume Kientz, Review of the exhibition catalogue, Víctor Nieto Alcaide, ed., Goya: La ribellione della ragione (ORE Cultura, 2023), pp. 872–74.

• Timothy Wilson, Review of Marino Marini, Maiolica and Ceramics in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello, translated by Anna Moore Valeri (Allemandi, 2024), pp. 876–77.

• J. V. G. Mallet, Review of Caterina Marcantoni Cherido, Maioliche italiane del Rinascimento (Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia, 2022), pp. 877–79.

• Aurora Laurenti, Review of Esther Bell, Pauline Chougnet, Sarah Grandin, Charlotte Guichard, Corinne Le Bitouzé, Anne Leonard, and Meredith Martin, Promenades on Paper: Eighteenth-Century French Drawings from the Bibliotheque nationale de France / Promenades de papier: Dessins du XVIIIe siècle des collections de la Bibliothèque nationale de France (Clark Art Institute and BnF Editions, 2023), pp. 883–84.

• Clare Hornsby, Review of Christopher M.S. Johns, Tommaso Manfredi, and Karin Wolfe, eds., American Latium: American Artists and Travelers in and around Rome in the Age of the Grand Tour (Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, 2023), pp. 884–86.

• Lydia Hamlett, Review of John Laycock, William Kent’s Ceiling Paintings at Houghton Hall (Houghton Arts Foundation, 2021), p. 887.

• Lin Sun, Review of Shane McCausland, The Art of the Chinese Picture-Scroll (Reaktion Books, 2023), pp. 887–88.

Call for Submissions | Metropolitan Museum Journal

Metropolitan Museum Journal 60 (2025)

Submissions due by 15 September 2024

The Editorial Board of the peer-reviewed Metropolitan Museum Journal invites submissions of original research on works of art in the Museum’s collection. The Journal publishes Articles and Research Notes. Works of art from The Met collection should be central to the discussion. Articles contribute extensive and thoroughly argued scholarship—art historical, technical, and scientific—whereas Research Notes are narrower in scope, focusing on a specific aspect of new research or presenting a significant finding from technical analysis, for example. Articles and Research Notes in the Journal appear in print and online, and are accessible in JStor on the University of Chicago Press website. The maximum length for articles is 8,000 words (including endnotes) and 10–12 images, and for research notes 4,000 words (including endnotes) and 4–6 images.

The process of peer review is double-anonymous. Manuscripts are reviewed by the Journal Editorial Board, composed of members of the curatorial, conservation, and scientific departments, as well as scholars from the broader academic community. Submission guidelines are available here. Please send materials to journalsubmissions@metmuseum.org. The deadline for submissions for volume 60 (2025) is 15 September 2024.

The Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust, Summer 2024

The Decorative Arts Trust has shared select articles from the summer issue of their member magazine as online articles for all to enjoy. The following articles are related to the 18th century:

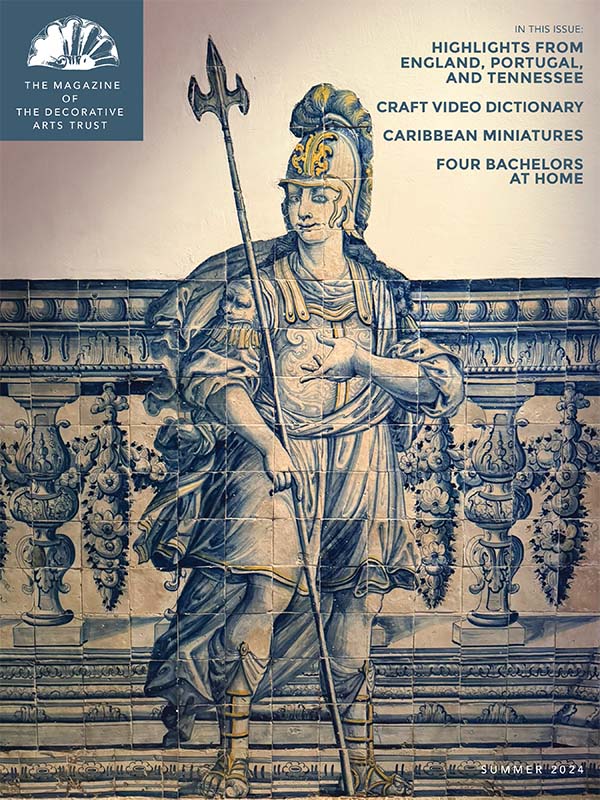

The Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust, Summer 2024

• “A Primer on Portugal” by Matthew A. Thurlow Link»

• “A Primer on Portugal” by Matthew A. Thurlow Link»

• “Saltram’s Saloon: Adam, Chippendale, and Reynolds in England’s West Country” by Catherine Carlisle Link»

• “Understanding Craft: A New Digital Tool Debuts” by Emily Zaiden Link»

• “Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800: Highlights from LACMA’s Collection” by the Saint Louis Art Museum Link»

• “Painted Walls: New Virtual Museum Offers an Immersive Experience” by by Margaret Gaertner and Kathleen Criscitiello Link»

• “Seafaring Portraits in Bermuda and the Atlantic Basin” by Damiët Schneeweisz Link»

• “Summer Reading Recommendation: Ceramic Art” by Jessie Dean Link»

The printed Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust is mailed to Trust members twice per year. Memberships start at $50, with $25 memberships for students.

Pictured: The magazine cover features a detail of wall tile from the stair hall of the Palácio Azurara in Lisbon, home of the Fundação Ricardo do Espírito Santo Silva’s decorative arts museum. Bartholomeu Antunes, Tile with the Figure of a Praetorian Guard, 1730–40, Lisbon. Earthenware tile with blue and yellow decoration.

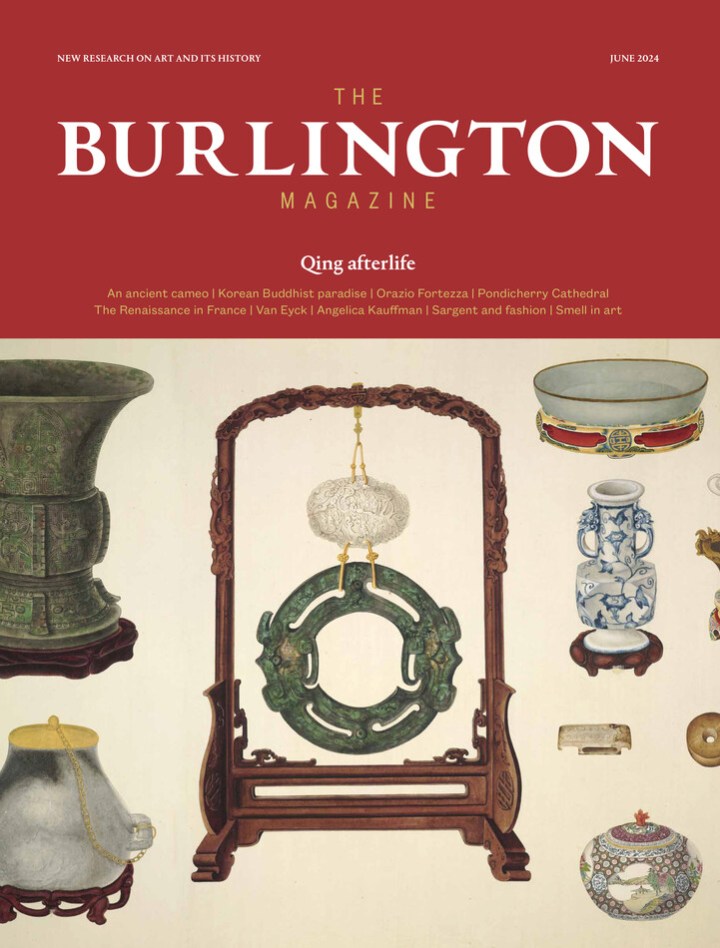

The Burlington Magazine, June 2024

Summer is for falling behind . . . and for catching up . . . The long 18th century in the June issue of The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 166 (June 2024)

e d i t o r i a l

• “La Serenissima,” p, 543.

• “La Serenissima,” p, 543.

Henry James famously wrote in his Italian Hours (1909) that there is nothing more to be said about Venice. As so much ink has been spilt over its charms you can see his point. However, James then proceeded to rhapsodise at length about its beauty; and it is imperative that we, similarly, keep talking and writing and championing it, not least because all that it represents seems to be more precious and precarious than ever.

a r t i c l e s

• Ittai Gradel, “Nothing To Do with Menander: A Rediscovered Roman Cameo from the Caylus Collection,” pp. 546–53.

A Roman cameo published in 1752, but since lost, has been rediscovered. It shows actors rehearsing The Pimp by Posidippus, who portrait is included on the cameo. All other identifiable scenes of comedies in Roman art depict plays by Menander, the most popular Greek comic poet on the Roman stage.

• Gauvin Alexander Bailey, “The Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-la-Conception, Pondicherry,” pp. 580–95.

When the cathedral at Pondicherry, the most ambitious in French India, was begun in 1771, its anonymous designer was obliged to make allowance for separation of the castes, despite a papal edict that they must attend public worship together. The cathedral was completed with the construction of its west facade in 1788–91; its design was based on seventeenth-century Parisian models and is here attributed to the engineer-architect François-Anne-Maire Rapine de Saxy.

• Ricarda Brosch, “The Art of Qing Imperial Afterlife: The Pictures of Ancient Playthings (Guwantu 古玩圖) Revisited,” pp. 596–611.

Two magnificent eighteenth-century handscrolls depict myriad precious objects made of jade, bronze, porcelain, glass, and bamboo. A novel interpretation of their function suggests that the illustrations were originally for wall decorations and remounted as scrolls for the Yongzheng Emperor’s tomb. The paintings’ remediation and repurposing offer a compelling example of the art of Qing imperial afterlife.

r e v i e w s

• Johnny Yarker, Review of the exhibition Angelica Kauffman (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2024), pp. 620–23.

• William Barcham, Review of Martin Gayford, Venice: City of Pictures (Thames & Hudson, 2023), p. 653.

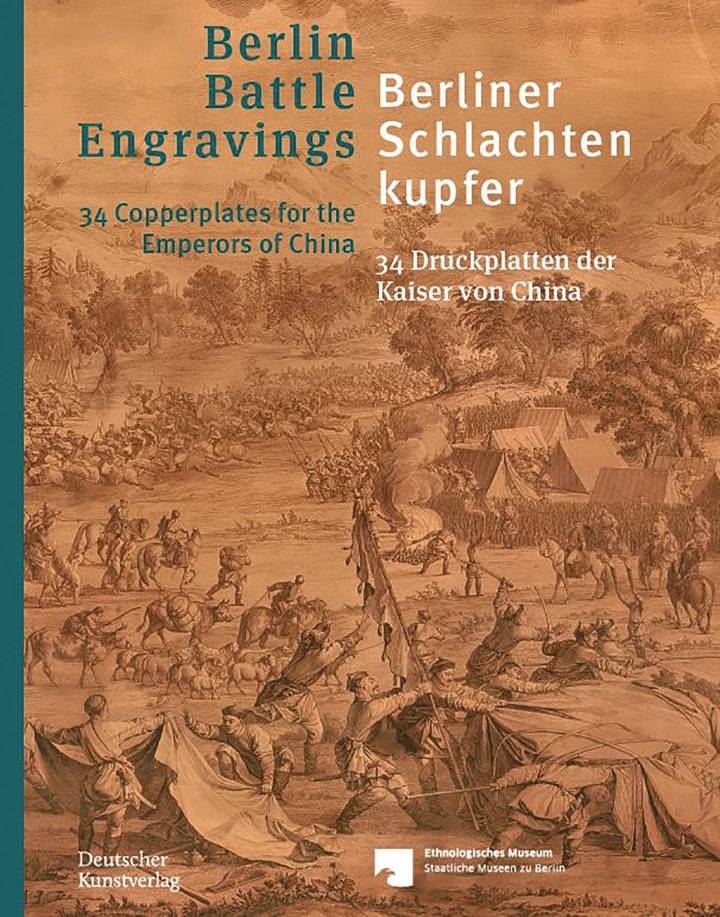

• Lianming Wang, Review of Henriette Lavaulx-Vrécourt and Niklas Leverenz, Berliner Schlachtenkupfer: 34 Druckplatten der Kaiser von China / Berlin Battle Engravings: 34 Copperplates for the Emperors of China (Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021), pp. 654–55.

• Amina Wright, Review of Frédéric Ogée, Thomas Lawrence: Le génie du portrait anglais (Cohen & Cohen, 2022), pp. 655–56.

• Barry Bergdoll, Review of Didem Ekici, Patricia Blessing, Basile Baudez, eds., Textile in Architecture: From the Middle Ages to Modernism (Routledge, 2023), pp. 662–63.

Oxford Art Journal, March 2024

In the latest issue of the Oxford Art Journal:

Oxford Art Journal 47.1 (March 2024), published June 2024.

a r t i c l e s

• Matthew C. Hunter and Avigail Moss, “Art and the Actuarial Imagination: Propositions,” pp. 1–12.

• Matthew C. Hunter and Avigail Moss, “Art and the Actuarial Imagination: Propositions,” pp. 1–12.

Noting insurance’s importance will hardly come as a surprise to curators, artists, conservators, and others concerned with current practices of exhibiting art. “Art insurance,” as one commentator observes, “is huge business and not least now that artworks move around the world in far greater volume and frequency than ever before.”6 Similarly, insurance and its extensive profiteering—from the trade in enslaved peoples to its biopolitical work in capitalist modernity—have been powerfully thematised by Cameron Rowland, Rana Hamadeh, and numerous other contemporary artists (Fig. 1).7 Yet, academic art history has been conspicuously slow to reckon with insurance’s force, functions, and fictions. This special issue is meant less as a reprimand for that blind spot than as a prompt to disciplined conversation. Drawing primarily upon the archive of European and North American art practices from the eighteenth century to the present, we mean to agitate for greater attention to how, when, where, and why insurance has come to penetrate art’s making, moving, showing, selling, storing, and being.

• Nina Dubin, “‘Infidelity, Imposture, and Bad Faith’: Reproducing an Insurance Bubble,” pp. 13–37.

When Grayson Perry commemorated the 2008 financial crisis with an etching titled Animal Spirit, he participated in a longstanding tradition of deploying printed images to satirize and demystify a boom-and-bust economy. More specifically, his print recalls a wave of caricatures that circulated in 1720 amidst a pan-European crash: one precipitated by a bubble in hypothetical commodities, foremost among them shares in joint-stock insurance companies. Produced by a group of Amsterdam-based artists including Bernard Picart, such engravings catered to a public that, already in 1720, viewed the business of insurance as occupying the vanguard of an inscrutable financial culture. Not only do these works exemplify early modern artistic efforts to translate into visual form the abstractions of an increasingly financialized economy. They also critically engage with the insurance operations of print, at a time when engraved reproductions presented themselves as policies that safeguarded works of art from the risks of accident and loss.

• Matthew C. Hunter, “The Sun Is God: Turner, Angerstein, and Insurance,” pp. 39–65.

J. M. W. Turner’s Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhon Coming On (also known as The Slave Ship) is probably the iconic visualization of insurance logic in Western art. Exhibited in 1840, the painting has come to be taken as a meditation on the jettison of one hundred thirty three captives from the slave ship Zong off Jamaica in late 1781, murders notoriously claimed as insurable losses from the ship’s underwriters. Less noted is the pervasive presence of insurance within Turner’s practice and milieu. This article follows the tandem of Turner and John Julius Angerstein (1735–1823), a leading underwriter at Lloyd’s of London and an early patron. It places them within a world of artists’ organizations being remade as political instruments by embracing life insurers’ actuarial tables. It traces the pair into the National Gallery (originally housed in Angerstein’s home) as Turner willed his art to the institution, contingent on the purchase of fire insurance. Revisiting The Slave Ship through this skein of underwriting activity, the article posits the Turner/Angerstein coupling as an instructive moment in insurance’s penetration through the thick of artistic practice.

• Richard Taws, “Charles Meryon’s Graphic Risks,” pp. 67–94.

This article considers the place of risk and fictitious value in the work of French printmaker Charles Meryon. Meryon is best-known for the Eaux-fortes sur Paris, the vertiginous etchings of the city he made between 1850 and 1854. Yet despite his close association with the metropolis, Meryon’s visual world was not limited to the French capital. Previously a sailor, he had travelled widely, notably to the South Pacific, to protect speculative whaling interests in New Zealand. At the peak of his career, in 1855, Meryon designed share certificates for an unrealised Franco-Californian property development company, whose owners commissioned from Meryon a panorama of San Francisco. Meryon’s certificate prints have not been discussed at length in the literature on the artist. In the years following the 1848 Revolution, thousands of French workers emigrated to California, and Meryon’s famous etchings of Paris were made against the backdrop of contemporary enthusiasm for the California Gold Rush; these phenomena should, I suggest, be understood together. Focusing on Meryon’s connections to construction and extraction schemes, lotteries, mass emigration, and insurance, this paper reorients analysis of Meryon’s work away from Paris towards more transnational, transatlantic networks of people and things. Reviewing Meryon’s practice in the light of these works, I argue that they illuminate an actuarial imagination at work.

• Ross Barrett, “Sculpting the ‘Idea of Insurance’: John Quincy Adams Ward’s Protection Group and the Rise of the American Life Sector,” pp. 95–115.

This essay examines John Quincy Adams Ward’s Protection Group (1871), a now-lost sculpture that ornamented the original New York headquarters of the Equitable Life Assurance Society, as a complex cultural response to the array of public relations problems that its patron and the broader life insurance sector faced in the decades after the Civil War. Adopted as a company logo at the very moment that the Equitable took steps to expand its insurance portfolio and extend the geographic range of its operations, the Protection Group outlined an imaginative allegory of indemnification that explained the benefits of the company’s policies, popularized actuarial conceptions of status, risk, and uncertainty, and set the terms for a wave of cultural promotions and rebranding efforts that would be undertaken by American life companies in the decades that followed. Tracing the work that the Protection Group did to smooth the way for the Equitable’s development into a multinational insurer and inure turn-of-the century consumers to the financial products and risk sensibilities of the life sector, this essay sheds new light on the pivotal contributions that academic sculptors made to the development of the modern US life insurance industry.

• Avigail Moss, “Ars Longa,Vita Brevis: The Fine Art & General Insurance Company, Ltd,” pp. 117–40.

In late-nineteenth-century Britain, artworks circulated widely between exhibitions, institutions, and marketplaces, increasing the risks of destruction and loss. Administrators, artists, and collectors offset these risks by turning to a key incidental service in capitalism: insurance. But how did artworks and artifacts test insurance underwriters’ capacities? And how did the insurance world impact the art world? This article introduces the Fine Art & General Insurance Company, Ltd, a firm established in London in 1890. As a unique collaboration between art workers and powerful City merchants and underwriters, the company operated for nearly a century, insuring works that travelled to international and domestic expositions, and underwriting collections like the National Gallery’s Chantrey Bequest. With branches and agents stationed in global metropoles, and with ties to the broader British imperium, the company was a key, if inconspicuous, power broker and proxy on the global cultural stage. As an economic and aesthetic gatekeeper, the company also adjudicated on the artworks it perceived to be acceptable risks, and I argue that by analysing its early activities we gain insight into the ways that art insurance—an inherently collective and even speculative activity—was already affecting art’s ecosystems before the twentieth century.

• Sophie Cras, “Art and Insurance after the Era of Statistics,” pp. 141–57.

This article focuses on two artworks made in 2010 by two French artists of different generations: Christian Boltanski’s The Life of C.B. and Julien Prévieux’s Les connus connus, les inconnus connus et les inconnus inconnus. Both resulted from the collaboration between the artist and an actuary-mathematician, at a time when the theoretical, technical and professional assumptions about statistics-based insurance were deeply shaken by the emergence of so-called ‘big data’ and ‘global catastrophic risks’. This vacillation is perceptible in the artists’ choices to represent—and make use of—quantitative, actuarial knowledge. Boltanksi’s video work stages the transformations of life insurance under the data deluge produced by connected technologies of ‘quantified self’. Prévieux’s sound installation displays the techniques of prospective actuarial imagination, when experts mix fact and fiction so as to quantify global catastrophic risks that exceed our capacities to foresight. Therefore, instead of showcasing the implacable efficiency of data-driven technologies, both artists humorously emphasize their inadequacy in the chain of knowledge, prediction, and action.

b o o k r e v i e w s

• Arie Hartog, “Viewing Broken Things: Review of Stacy Boldrick, Iconoclasm and the Museum (Routledge, 2020),” pp. 159–62.

• Ty Vanover — The Spectacle of Crime: Review of Frederic Schwartz, The Culture of the Case: Madness, Crime, and Justice in Modern German Art (The MIT Press, 2023),” pp. 162–66.

• Jennifer Sichel — A Feminist Queering: Review of Julia Bryan-Wilson, Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture: Drag, Color, Join, Face (Yale University Press, 2023),” pp. 166–68.

Abstracts

Notes on Contributors

Essay | Caroline Gonda on Anne Seymour Damer

Caroline Gonda recently published this essay on The British Museum’s Blog, with lots of images and links for relevant items, including the drawing reproduced here.

Caroline Gonda, “Anne Seymour Damer: Public Life, Private Love,” The British Museum Blog (27 June 2024). Gossip about Anne Seymour Damer’s sexuality nearly wrecked her relationships and reputation, but in this queer love story, love beats scandal.

John Downman, Study for a Portrait of Anne Damer, charcoal, touched with red chalk, 1788 (London: The British Museum, 1967,1014.181.141).

‘Social media’ ruined lives in the 18th century, just as it does today. Anne Seymour Damer (1748/9–1828) was a sculptor (a highly unusual career for a woman artist at the time) and an aristocrat, which made her a part of celebrity culture and particularly exposed to gossip. Damer was also the subject of scandal because of her intimate relationships with other women. One of her contemporaries, the writer and literary hostess Hester Piozzi, described her as ‘a lady much suspected for liking her own sex in a criminal way’. Damer was repeatedly labelled as a Sapphist. The term was an allusion to the ancient Greek poet Sappho; famous for her love poems, many of them addressed to other women, Sappho was beginning to be seen in this period as the original lesbian (a term drawn from her birthplace of Lesbos). The gossip put Damer’s reputation at risk, but also sabotaged her chances of finding—and keeping—love. . .

The full essay is available here»

Caroline Gonda is College Associate Professor and Glen Cavaliero Fellow in English at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge.

The Burlington Magazine, May 2024

From the May issue of The Burlington, which is dedicated to French art — and please note that Yuriko Jackall’s important article is currently available for free, even without a subscription.

Burlington Magazine 166 (May 2024)

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1767, oil on canvas, 81 × 64 cm (London: Wallace Collection).

a r t i c l e s

• Ludovic Jouvet, “A Medal of the Sun King by Claude I Ballin,” pp. 440–45.

• Yuriko Jackall, “The Swing by Jean-Honoré Fragonard: New Hypotheses,” pp. 446–69.

• Thadeus Dowad, “Dāvūd Gürcü, Ottoman Refugee, and Girodet’s First Mamluk Model,” pp. 479–87.

• Humphrey Wine, “The Paintings Collection of Denis Mariette,” pp. 488–92.

r e v i e w s

• Richard Stemp, Review of Ingenious Women: Women Artists and their Companions (Hamburg: Bucerius Kunst Forum / Basel: Kunstmuseum, 2023–24), pp. 501–04.

• Christoph Martin Vogtherr, Review of Louis XV: Passion d’un roi (Château de Versailles, 2022), pp. 508–10.

• Eric Zafran, Review of The Hub of the World: Art in Eighteenth-Century Rome (Nicholas Hall, 2023), pp. 515–18.

• Saffron East, Review of Black Atlantic: Power, People, Resistance (Cambridge: Fitzwilliam, 2023), 523–25.

• Gauvin Alexander Bailey, Review of Marsely Kehoe, Trade, Globalization, and Dutch Art and Architecture:

Interrogating Dutchness and the Golden Age (Amsterdam UP, 2023), pp. 534–35.

• Helen Clifford, Review of Vanessa Brett, Knick-Knackery: The Deards’ Family and Their Luxury Shops, 1685–1785 (2023) pp. 535–37.

o b i t u a r y

• Michael Hall, Obituary for Jacob Rothschild (1936–2024), pp. 538–40.

One of the leading public figures in the arts in the United Kingdom, Lord Rothschild was a major collector of historic art and a patron of contemporary artists and architects. His principal focus was Waddesdon Manor, his family’s Victorian country house and estate in Buckinghamshire.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Jean-Honoré Fragonard was one of the supreme exponents of the French Rococo style and his painting The Swing in the Wallace Collection, London, is perhaps his most famous work. Yet despite this elevated status, mystery surrounds its origins. New documentary and technical research presented here by Yuriko Jackall may, however, have finally established for whom it was painted and why the painting was hidden away for the first few years of its existence.

The May issue also includes the publication by Ludovic Jouvet of a previously unknown and spectacular medal of the Sun King, Louis XIV, as well as Humphrey Wine’s study of the intriguing collection of the publisher Denis Mariette (the uncle of the more famous Pierre-Jean Mariette). Other articles feature the work of French Romantic painters: Andrew Watson establishes the early history of Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus in the Musée du Louvre, Paris, and Thadeus Dowad identifies Girodet’s first Mamluk model.

Exhibition reviews include Sarah Whitfield discussing Bonnard’s Worlds (Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, and the Phillips Collection, Washington) and Lisa Stein assessing Saul Leiter (MK Gallery, Milton Keynes). Catalogue reviews feature Christoph Martin Vogtherr on Louis XV, Lunarita Sterpetti on Eleonora of Toledo, and Eric M. Zafran surveying art in eighteenth-century Rome. Meanwhile, an impressive and wide range of new books are examined: these feature Megan McNamee on diagrams in medieval manuscripts, Christine Gardner-Dseagu on photographing Pompeii and Richard Thomson on Henry Lerolle.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Note (added 31 July 2024) — The posting was updated to include additional content.

Print Quarterly, June 2024

The long eighteenth century in the latest issue of Print Quarterly:

Print Quarterly 41.2 (June 2024)

a r t i c l e s

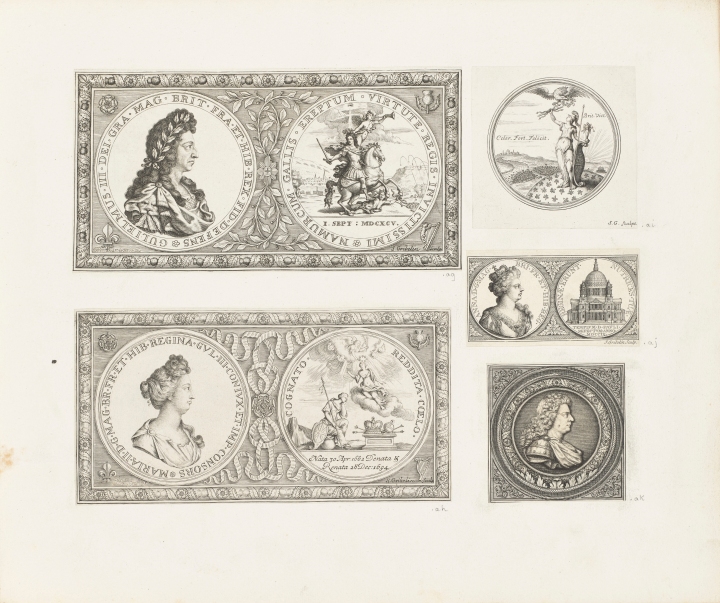

Simon Gribelin, A Medal of William III Commemorating the Fall of Namur, 1695 and other engravings, in the Works of Gribelin album, sheet 311 × 372 mm (Windsor Castle, Royal Collection. Image Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023).

• Rhian Wong, “Simon Gribelin’s Presentation Albums,” pp. 157–71.

The article examines two previously unpublished presentation albums in the Royal Collection, compiled by the engraver Simon Gribelin (1661–1733). The Works of Gribelin album was compiled in 1715 for George II (when Prince of Wales), while an album of prints of the ceiling of the Banqueting House, London was presented around 1720 to George I. A consideration of the contents of the Works of Gribelin album reveals that Gribelin followed a deliberate programme for the arrangement of its contents. The article looks at the purpose of the albums and places their creation in the context of four other albums known to have been assembled by Gribelin.

n o t e s a n d r e v i e w s

• Galina Mardilovich, Review of Julia Khodko, Peterburg Mikhaila Makhaeva. Grafika I zhivopis’ vtoroi poloviny XVIII veka (The State Russian Museum, 2022), pp. 183–85. This is the catalogue for an exhibition addressing the drawings (and resulting prints) of St Petersburg made by Mikhail Makhaev (1717–1770).

• Shijia Yu, Review of The Art of the Deal (Daniel Crouch Rare Books, 2023), pp. 185–87. This is catalogue of the playing card collection assembled by the Dutch collector Frank van den Bergh.

• Thea Goldring, Review of Esther Bell, Sarah Grandin, Corinne Le Bitouzé, and Anne Leonard, Promenades on Paper: Eighteenth-Century French Drawings from the Bibliothèque National de France (Yale University Press, 2022), pp. 188–90.

• Joanna Sheers Seidenstein, Review of Amy Golahny, Rembrandt’s Hundred Guilder Print (Lund Humphries, 2021), pp. 221–26. Includes the reception history of the print, and the section on William Baillie’s restrikes in the 1770s is relevant.

Journal18, Spring 2024 — Color

The latest issue of J18:

Journal18, Issue #17 (Spring 2024) — Color

Issue edited by Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Thea Goldring

Color has been at the center of artistic debates at least since the seventeenth century, and it has remained a key issue in the historiography of art. Recent research has largely pursued two directions. First, color has been studied as a material substance and a technology. Scholars have documented the relation between technological, industrial, and commercial developments and the quality, range, and availability of pigments and colorants available to artists, manufacturers, and consumers. A second approach has focused on the key role of color in the construction of social, racial, colonial, and gender hierarchies. Recent scholarship has revealed the intimate connection between aesthetic debates on chroma and the development of the modern discourse of race. The eighteenth century’s feminization of color, linked to make-up and artifice, has also been reexamined. Clearly, it is no longer viable to think of color or its materials, technologies, and processes in purely aesthetic, ideologically innocent terms. This issue of Journal18 considers what is at stake now in reconsidering color in its historical dimensions by bringing these two lines of research together.

Color has been at the center of artistic debates at least since the seventeenth century, and it has remained a key issue in the historiography of art. Recent research has largely pursued two directions. First, color has been studied as a material substance and a technology. Scholars have documented the relation between technological, industrial, and commercial developments and the quality, range, and availability of pigments and colorants available to artists, manufacturers, and consumers. A second approach has focused on the key role of color in the construction of social, racial, colonial, and gender hierarchies. Recent scholarship has revealed the intimate connection between aesthetic debates on chroma and the development of the modern discourse of race. The eighteenth century’s feminization of color, linked to make-up and artifice, has also been reexamined. Clearly, it is no longer viable to think of color or its materials, technologies, and processes in purely aesthetic, ideologically innocent terms. This issue of Journal18 considers what is at stake now in reconsidering color in its historical dimensions by bringing these two lines of research together.

The four articles and two notes in this issue explore how the current interest in materiality and the matter of art might be harnessed to alter—enrich, complicate, or challenge—our understanding of the historical functions and socio-cultural meanings of color in the long eighteenth century. . . .

a r t i c l e s

Andrea Feeser — When Blue and White Obscure Black and Red: Conditions of Wedgwood’s 1787 Antislavery Medallion

Caroline Culp — Embalming in Color: John Singleton Copley’s Vital Portraits at the Edge of Empire

Tong Su — Color in Taxidermy at the Eighteenth-Century Qing Court

Melissa Hyde — Men in Pink: The Petit-Maître, Refined Masculinity, and Whiteness

s h o r t e r p i e c e s

Tori Champion — Catherine Perrot: Color, Gender, and Medium in the Seventeenth-Century Académie

Philippe Colomban — The Quest for the Western Colors in China under the Qing Emperors

Écrans, 2024: William Hogarth et le cinéma

From Classiques Garnier, where individual articles are also available for purchase:

Marie Gueden and Pierre Von-Ow, ed., Écrans, Nr. 20: William Hogarth et le cinéma (Paris: Garnier, 2024), 295 pages, French and English, ISBN: 978-2406169727, €25.

This special issue of Écrans explores the largely overlooked and unexpected connections between William Hogarth and cinema. Frequently mentioned in passing, these links are thoroughly examined here by art historians, film and literary scholars, and a filmmaker. The collection addresses various crucial themes (such as narrative serialization, visual dynamics, and socio-cultural aspects), aiming to showcase the historical significance, artistic richness, and contemporary relevance of the relationship between Hogarth and cinema.

This special issue of Écrans explores the largely overlooked and unexpected connections between William Hogarth and cinema. Frequently mentioned in passing, these links are thoroughly examined here by art historians, film and literary scholars, and a filmmaker. The collection addresses various crucial themes (such as narrative serialization, visual dynamics, and socio-cultural aspects), aiming to showcase the historical significance, artistic richness, and contemporary relevance of the relationship between Hogarth and cinema.

Marie Gueden holds a PhD in film studies from Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne. Associate researcher at the Institut ACTE (Université Paris 1 – Panthéon-Sorbonne) and Passages XX-XXI (Université Lumière Lyon 2), lecturer at ENS Lyon and Université Sorbonne Nouvelle-Paris 3, she has published several articles, including studies on Sergei M. Eisenstein and William Hogarth.

Pierre Von-Ow recently received his PhD in History of Art from Yale University. His research focuses primarily on the intersections of arts and sciences in the early modern period. Among his recent projects, he curated in 2022 the virtual exhibition William Hogarth’s Topographies for The Lewis Walpole Library.

s o m m a i r e

• Marie Gueden et Pierre Von-Ow — Introduction: William Hogarth et le cinéma

I Sérialisation narrative et genres / Narrative Serialization and Genres

• Kate Grandjouan — Virtual witnessing in A Harlot’s Progress (1732). Hogarth’s visio-crime media

• Marie Gueden — Progress hogarthien et continuité narrative et morale aux États-Unis. Du pré-cinéma au cinéma des années 1930

• Brian Meacham and Yvonne Noble — An early film adaptation of Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones at Yale University

II Image et mouvement / Image and Movement

• Marie Gueden — « Hogarthisme » outre-Atlantique. Du tournant du XXe siècle aux années 1920–1930

• Marion Sergent — Sur la serpentine. Hogarth et l’abstraction musicaliste de Janin, Béothy et Valensi

• Jordi Xifra — Luis Buñuel, cinéaste hogarthien

• Théo Esparon — Beauté, glamour, baroque dans La Femme et le pantin (1935) de Josef von Sternberg

III Revoir Hogarth / Re-Viewing Hogarth

• Jean-Loup Bourget — Hogarth au cinéma, indice d’anglicité ?

• Pierre Von-Ow — Hogarth through a camera. Bedlam from print to film

• Enrico Camporesi — De Southwark Fair à Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son. Cinéma des origines et origines du cinéma

• Mike Leigh on Hogarth, Interview by Pierre Von-Ow

Annexes / Appendices

1 Angles and Pyramids (1936)

2 Pierre Kast — De la parodie de « Paméla » à « Tom Jones ». L’Angleterre georgienne, scénario de Henry Fielding, réalisation de Hoggarth (1948)

Filmographie

Résumés / Abstracts

leave a comment