Documentary | The American Revolution

The series premiers Sunday evening. Jill Lepore addresses it within the larger context of institutions celebrating the 250th anniversary of the Revolution, “Revolutionary Whiplash: Commemorating a Nation’s Founding in a Time of Fear and Foreboding,” The New Yorker (17 November 2025), pp. 14–18. . . . .

The American Revolution: A Film by Ken Burns, Sarah Botstein, and David Schmidt, 12 hours, PBS, 2025. With Claire Danes, Hugh Dancy, Josh Brolin, Kenneth Branagh, and Liev Schreiber.

The American Revolution examines how America’s founding turned the world upside-down. Thirteen British colonies on the Atlantic Coast rose in rebellion, won their independence, and established a new form of government that radically reshaped the continent and inspired centuries of democratic movements around the globe.

An expansive look at the virtues and contradictions of the war and the birth of the United States of America, the film follows dozens of figures from a wide variety of backgrounds. Through their individual stories, viewers experience the war through the memories of the men and women who experienced it: the rank-and-file Continental soldiers and American militiamen (some of them teenagers), Patriot political and military leaders, British Army officers, American Loyalists, Native soldiers and civilians, enslaved and free African Americans, German soldiers in the British service, French and Spanish allies, and various civilians living in North America, Loyalist as well as Patriot, including many made refugees by the war.

An expansive look at the virtues and contradictions of the war and the birth of the United States of America, the film follows dozens of figures from a wide variety of backgrounds. Through their individual stories, viewers experience the war through the memories of the men and women who experienced it: the rank-and-file Continental soldiers and American militiamen (some of them teenagers), Patriot political and military leaders, British Army officers, American Loyalists, Native soldiers and civilians, enslaved and free African Americans, German soldiers in the British service, French and Spanish allies, and various civilians living in North America, Loyalist as well as Patriot, including many made refugees by the war.

The Revolution began a movement for people around the world to imagine new and better futures for themselves, their nations, and for humanity. It declared American independence with promises that we continue to strive for. The American Revolution opened the door to advance civil liberties and human rights, and it asked questions that we are still trying to answer today.

Each episode is two hours.

1 | In Order to Be Free (May 1754 – May 1775)

2| An Asylum for Mankind (May 1775 – July 1776)

3 | The Times That Try Men’s Souls (July 1776 – January 1777)

4 | Conquer by a Drawn Game (January 1777 – February 1778)

5 | The Soul of All America (December 1777 – May 1780)

6 | The Most Sacred Thing (May 1780 – Onward)

Geoffrey Ward and Ken Burns, The American Revolution: An Intimate History (New York: Knopf, 2025), 608 pages, ISBN: 978-0525658672, $80.

At Christie’s | Largillièrre’s Portrait of a Woman

The leader of the Monuments Men, Capt. James Rorimer, and three soldiers after the rescue of artworks from Neuschwanstein Castle.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

As noted last month by Nina Siegal in The New York Times:

Nina Siegal, “For Sale: A Painting the Monuments Men Rescued from the Nazis,” The New York Times (25 October 2024). The portrait by a French court painter is one of three displayed in a photo that came to depict the efforts of a U.S. Army unit that tracked legions of looted art.

Nicolas de Largillièrre (1656-1746), Portrait of a Woman Half-Length, oil on canvas, 81 × 65 cm. To be sold at Christie’s Paris, 21 November 2024 (Sale #23018, Lot 27), estimate: €50,000–80,000.

It appears, memorably, in a snapshot taken in May 1945 of American soldiers on the steps of Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria—a painted portrait of a woman in a shimmering gown with porcelain skin and curly silver hair. The portrait and two other old master paintings are held by American soldiers in combat fatigues who have just liberated them from a Nazi storehouse of looted art.

The G.I.s were helping the Monuments Men, a special U.S. Army unit that tracked down millions of works of art stolen by the Germans during World War II. The image became a resonant depiction of the unit’s role in undoing Nazi evil and restoring part of European heritage to its rightful place.

Now the portrait, by the French court painter Nicolas de Largillièrre from the era of Louis XIV, is to be auctioned next month at Christie’s. . .

The full article is available here»

Note (added 22 November 2024) — The portrait sold for €529,200 (ten times more than its low estimate).

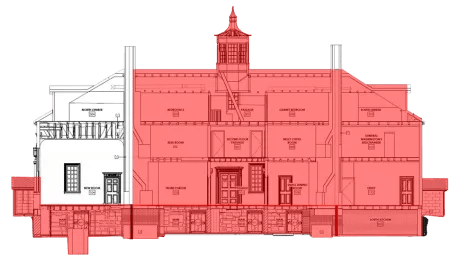

Mount Vernon Enters Next Phase of $30million Restoration

From coverage of the project by The Washington Post:

Michael Ruane, “George Washington’s Mansion Gets First Major Rehab in More than 150 Years,” The Washington Post (17 October 2024). Much of the historic Mount Vernon home in Virginia will close starting next month for a massive preservation project.

. . . On Nov. 1, the bulk of Washington’s famous home is due to close for several months as it undergoes the next phase of its largest-scale rehabilitation in over 150 years.

In Phase 2, scheduled to run from November 2024 until January 2025, the New Room, Servants’ Hall, and Kitchen are open; all other rooms will be closed to visitors.

The $30 million project is the most complicated preservation effort since the house was saved from decay in 1860 by the private, nonprofit Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, which still owns it, said Douglas Bradburn, president of George Washington’s Mount Vernon. “We’re shutting down a big chunk of it for the next eight months or so,” he said. “I would say that’s two-thirds of the house.”

Other parts of the house, along with the extensive grounds, Washington’s tomb, the quarters for enslaved people and other outbuildings will remain open, Bradburn said in a recent interview. Mount Vernon gets about 1 million visitors a year, and millions more check out the historic estate online, he said.

The historic structure had become loosened from its foundation over time, and the work will resecure it, Bradburn said. There also will be restoration work done in the basement and on flooring, among other things. He said the goal is to complete the project in 2026.

“It’s some of the most important work that’s ever been done at Mount Vernon,” Bradburn said. Earlier repair projects have been piecemeal. At one point, ship masts were used to help support the roof of the crumbling piazza that overlooks the Potomac River. “They’re dealing with problems as they come,” he said. This is a chance for a more complete approach. . .

The full article is available here»

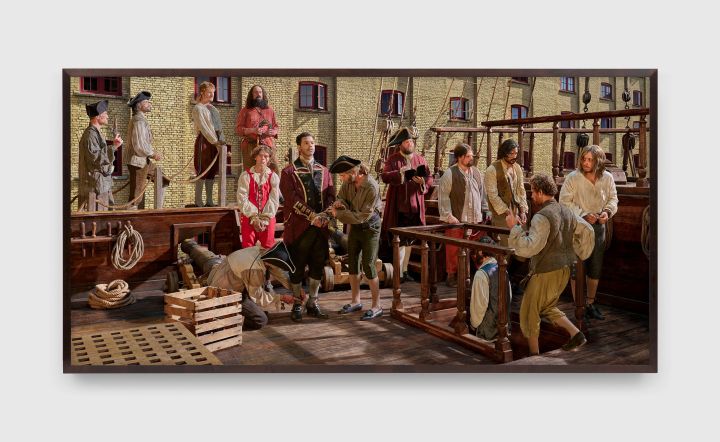

Exhibition | Stan Douglas: The Enemy of All Mankind

Stan Douglas, Act II, Scene XII: In which Polly Convinces Pirates Laguerre and Capstern to Release their Captive, Prince Cawwawkee, for a Prize Rather than go to War Against His People with Morano, 2024, inkjet print mounted on Dibond aluminum, 150 × 200 cm, edition of 5.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the press release for the show, which was covered by Walker Mimms for The New York Times (17 October 2024). . .

Stan Douglas | The Enemy of All Mankind: Nine Scenes from John Gay’s Polly

David Zwirner, New York, 12 September — 26 October 2024

David Zwirner is pleased to announce an exhibition by Stan Douglas, on view at the gallery’s 525 West 19th Street location in New York. Featuring a new photographic series, The Enemy of All Mankind: Nine Scenes from John Gay’s Polly, this will be the artist’s eighteenth solo exhibition with the gallery. In this stand-alone group of nine images, Douglas stages scenes from the eighteenth-century comic opera Polly, written by English dramatist John Gay (1685–1732), using the narrative as a vehicle through which to engage a wide range of themes that remain highly relevant today, including race, class, gender, and media. One work from the series debuted in David Zwirner: 30 Years, on view in summer 2024 in Los Angeles, and this will mark the first presentation of the body of work in its entirety.

Since the 1980s, Douglas has created films, photographs, and other multidisciplinary projects that investigate the parameters of their respective mediums. His ongoing inquiry into technology’s role in image making, and how those mediations infiltrate and shape collective memory, has resulted in works that are at once specific in their historical and cultural references and broadly accessible. Since the beginning of his career, photography has been a central focus of Douglas’s practice, used at first as a means of preparing for his films and eventually as a powerful pictorial tool in its own right. The artist is influenced in particular by media theorist Vilém Flusser’s notion of the photographic image as an encoded language that is determined by a specific set of technological, social, cultural, and political circumstances.

Stan Douglas, Overture: In which Convicted Brigand Captain Macheath is Transported to the West Indies Where He will be Impressed into Indentured Labour, 2024, inkjet print mounted on Dibond aluminum, 150 × 200 cm, edition of 5.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

A sequel to Gay’s well-known The Beggar’s Opera (which was later adapted as The Threepenny Opera), Polly was censored by the British government for its embedded satire and critique, particularly of policies around the parceling out of land; as a result, it was never produced during Gay’s lifetime. Douglas further notes that Polly was ahead of its time, as it “satirizes imperial patriarchal hierarchies of race and class—as well as gender norms, which it depicts as performative” (Douglas, in correspondence with the gallery, March 2024).

Gay’s stage play follows the eponymous Polly Peachum, who travels to the West Indies to search out her estranged husband, Captain Macheath, who has disguised himself as a Black man known as Morano and adopted the life of a pirate. Upon her arrival on the island, Polly is, unbeknownst to her, sold to a wealthy plantation owner as a courtesan. After eventually securing her freedom, she is advised to disguise herself as a young man to ward off unwanted male attention, and as a result becomes entangled in a series of skirmishes between the colonial settlers, the native population, and the pirates.

To create the photographs—which were shot in Jamaica using Hollywood-level production effects—Douglas enlisted a cast of actors to read from a loose script that he adapted for the chosen scenes, modifying certain characters and elements to bring the themes in line with the present day. For example, in Douglas’s version, Captain Macheath was a Black man passing as white in London who, once in the West Indies, drops the disguise and lets his hair grow out. Rather than posing the players, he photographed them continuously as they acted out and improvised the dialogue, then selected as the final images those that best embodied the ideas put forth in the narrative. The resulting large-scale photographs are dynamically realized, taking the form of sweeping tableaux where dramatis personae and setting collide in vivid color. Retaining Gay’s sense of comedic folly and satire as well as the underlying pathos of the story, the images bear traces of the various forms of media through which they have been filtered, employing formal elements drawn from theatrical, cinematic, and photographic conventions alike. Accordingly, Douglas positions the viewer as a spectator—a voyeuristic witness to the various narrative turns and apparent absurdities in which relationships are transactional and enemies expendable.

Stan Douglas, Act II, Scene VI: In which the Wife of Pirate Captain Morano, Jenny Diver, Attempts to Seduce Polly, who is Disguised as a Man to Avoid Molestation, detail, 2024, inkjet print mounted on Dibond aluminum, 150 × 150 cm, edition of 5.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Douglas’s use of Polly as the basis for this project arose out of his long-standing interest in maroon societies, large groups of enslaved persons who banded together to run away and start new, proto-democratic societies. Contrary to their depiction in popular media, pirate ships occasionally functioned as collaborative maroon societies in their own right. The title of the series, The Enemy of All Mankind, is taken from a doctrine of eighteenth-century maritime law (in Latin, hostis humani generis) under which pirates could be attacked by anyone since they fell outside the protection of any nation, but its core notion of defining certain groups as enemies or outsiders resonates broadly today. In Polly, the pirates—in contrast to the settlers and indigenous people—are meant to embody immorality and evil, yet in pulling out specific strands of the narrative, Douglas points to a more nuanced understanding of such sweeping generalities.

Stan Douglas (b. 1960) was born in Vancouver and studied at Emily Carr College of Art in Vancouver in the early 1980s. Douglas was one of the earliest artists to be represented by David Zwirner, where he had his first American solo exhibition in 1993—the second show in the gallery’s history.

Douglas’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at prominent institutions worldwide since the 1980s. In 2022, the artist represented his native Canada at the Venice Biennale, where he debuted a major video installation, ISDN (2022)—now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and The Museum of Modern Art, New York—and a related body of photographs. Subsequently, the exhibition Stan Douglas: 2011 ≠ 1848 traveled around Canada with stops at The Polygon Gallery, Vancouver (fall 2022); Remai Modern, Saskatoon (February–April 2023); and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa (September 2023–October 2024). A solo exhibition also titled 2011 ≠ 1848 was subsequently staged in 2023 at De Pont Museum, Tilburg, the Netherlands. In 2023, this body of work inaugurated David Zwirner’s new Los Angeles location, and it is currently on view at the Parque de Serralves in Porto, Portugal, through 12 January 2025.

Douglas has been the recipient of notable awards, including the Audain Prize for Visual Art (2019); the Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography (2016); the third annual Scotiabank Photography Award (2013); and the Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography, New York (2012). In 2021, Douglas was knighted as a Chevalier of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Minister of Culture, and in 2023 he was awarded an honorary doctorate by Simon Fraser University, Greater Vancouver. Work by the artist is held in major museum collections worldwide.

The Descendants Project Purchases Woodland Plantation House

Woodland Plantation House, LaPlace, Louisiana, the oldest portions of which date to 1793. The Descendants Project purchased the house and four acres of land in January 2024 for $750,000. More information is available here»

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From National Public Radio:

Debbie Elliott, “Louisiana Plantation Where Historic Slave Revolt Started Now under Black Ownership,” NPR Morning Edition (9 July 2024).

Jo Banner is excited to show the newly acquired Woodland Plantation House near the banks of the Mississippi River.

“We have still a lot of work to do, but I think for the home to be from 1793, it looks rather good,” she beams.

The raised creole-style building has a rusty tin roof and a wide front porch. Forest green wooden shutters cover the windows and doors. The site is historically significant because this is where one of the largest slave revolts in U.S. history began. It’s also known as the German Coast Uprising because this region was settled by German immigrants.

“The start of the 1811 revolt happened here, on this porch,” Banner says.

Banner and her twin sister Joy are co-founders of the Descendants Project, a non-profit in Louisiana’s heavily industrialized river parishes—just west of New Orleans. Early this year, the group bought the Woodland Plantation Home, putting it in Black ownership for the first time [in its over 200-year history] . . .

“Our mission is to eradicate the legacies of slavery so for us, it’s the intersection of historic preservation, the preservation of our communities, which are also historic, and our fight for environmental justice,” says Joy Banner.

The full report is available here»

More information on the house is available at the Society of Architectural Historians’ Archipedia site»

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

About The Descendants Project:

The Descendants Project is an emerging organization committed to the intergenerational healing and flourishing of the Black descendant community in the Louisiana river parishes. The lands of the river parishes hold the intersecting histories of enslavement, settler colonialism, and environmental degradation.

We are descended from the enslaved men, women, and children who were forced to labor at one or more of the hundreds of plantations that line the Mississippi River from New Orleans to Baton Rouge. Starting in the 1970s, large industrial petrochemical plants began purchasing the land of these plantations still surrounded by vulnerable Black descendant communities. The region is now known as ‘Cancer Alley’ for the extreme risks of cancer and death due to pollution. The community faces many other problems such as food insecurity, high unemployment, high poverty, land dispossession, and health issues that stem from a culture of disregard for Black communities and their quality of life.

Through programming, education, advocacy, and outreach, The Descendants Project is committed to reversing the vagrancies of slavery through healing and restorative work. We aim to eliminate the narrative violence of plantation tourism and champion the voice of the Black descendant community while demanding action that supports the total well-being of Black descendants.

The San José in the News

Samuel Soctt, Action off Cartagena, 28 May 1708, 1740s, oil on canvas (Greenwich: National Maritime Museum, BHC0348). Under the leadership of Commodore Wager, the Expedition (shown in the center) fires on the San José (left of center).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

In 1708, during the War of Spanish Succession, the San José was destroyed by a British squadron under Charles Wager (for whom a ship was named in the 1730s, that ship again made famous by David Grann’s recent best-seller). From The New York Times:

Remy Tumin and Genevieve Glatsky, “A Treasure May Be off the Coast of Colombia, but Who Can Claim It?” The New York Times (10 November 2023). The San José galleon was destroyed in 1708, sinking with goods now worth billions. Colombia’s government is planning a recovery, but not everyone wants to see the shipwreck brought to the surface.

When the San José made its final voyage from Seville, Spain, to the Americas in 1706, the Spanish galleon was considered to be one of the most complex machines ever built.

But in an instant, the armed cargo vessel went from a brilliant example of nautical architecture to what treasure hunters would come to consider the Holy Grail of shipwrecks. The San José was destroyed in an ambush by the British in 1708 in what is known as Wager’s Action, sinking off the coast of Cartagena, Colombia, with a haul of gold, jewels, and other goods that could be worth upward of $20 billion today.

Some experts say that number is extraordinarily inflated. But the myth built around the San José has prompted the Colombian government to keep its exact location a secret as a matter of national security.

Now Colombia’s president, Gustavo Petro, wants to accelerate a plan to bring the ship and its contents to the surface—and everyone wants a piece of it. It is the latest maneuver in a decades-long drama that has pitted treasure hunters, historians and the Colombian government against one another. . . .

Archaeologists and historians have condemned the effort, arguing that disturbing the ship would do more harm than good. Multiple parties, including Colombia and Spain, have laid claim to the San José and its contents. Indigenous groups and local descendants of Afro-Caribbean communities argue they are entitled to reparations because their ancestors mined the treasure.

Perhaps the largest, most enduring conflict is in the hands of an international arbiter in London. . . .

The full article is available here»

A Portrait by Rosalba Carriera Newly Discovered

A Santini prayer found in Rosalba Carriera’s Portrait of a Tyrolese Lady helped identify the piece as an original by the artist (Photo from Tatton Park and the National Trust). For more information on these paper prayers, see the catalogue for the recent exhibition in Dresden, Rosalba Carriera: Perfection in Pastel.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

As reported recently by a few media outlets, including ArtNet:

Sarah Cascone, “A Frick Curator Has Just Identified Rosalba Carriera as the Artist Behind an Unknown Portrait Languishing in Storage for Decades,” ArtNet (16 October 2023). A Roman Catholic prayer card slipped between the portrait and its frame offered proof that this was an original Carriera.

For 35 years, a delicate pastel portrait languished in storage at Tatton Park, a historic estate in Knutsford, Cheshire, in the UK. Then came a call from a curator in New York, asking to take a look. The work, it turned out, was by Rosalba Carriera, the renowned Venetian Rococo painter and pastelist, and one of art history’s most successful women artists.

Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of a Tyrolese Lady, pastel (Tatton Park and the National Trust).

The rediscovery came courtesy of Xavier Salomon, curator and deputy director at New York’s Frick Collection, who became interested in the Italian artist after the museum received a donation of two of her works in 2020.

“The more I started working on her, I realized there was a need for a new catalogue raisonné and biography,” Salomon said in a phone interview. “It’s going to take many years because she has hundreds of pastels all around the world, and I am just trying to see every single one of them.”

To date, the curator has looked at more than 200 Carriera pastels—but he’s also seen plenty, that while attributed to the artist, were actually copies by other artists. Tatton Park was just one of five homes in the UK’s National Trust Salomon had on his itinerary, one of which had a suite of five that turned out to be the work of British artists. But he was hopeful about Tatton Park, which, according to the National Trust’s inventory, had owned the Portrait of a Tyrolese Lady, identified as the work of Carriera, since the 18th century. . .

The full article is available here»

In the News | ‘Prize Papers’ in UK’s National Archives

Photograph from The Prize Papers Project.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From The NY Times (and Art Daily) . . .

Bryn Stole, “Long-Lost Letters Bring Word, at Last,” The New York Times (9 March 2023). Researchers are sorting through a centuries old cache of undelivered mail that gives a vivid picture of private lives and international trade in an age of rising empires.

In a love letter from 1745 decorated with a doodle of a heart shot through with arrows, María Clara de Aialde wrote to her husband, Sebastian, a Spanish sailor working in the colonial trade with Venezuela, that she could “no longer wait” to be with him.

Later that same year, an amorous French seaman who signed his name M. Lefevre wrote from a French warship to a certain Marie-Anne Hoteé back in Brest: “Like a gunner sets fire to his cannon, I want to set fire to your powder.”

Fifty years later, a missionary in Suriname named Lene Wied, in a lonely letter back to Germany, complained that war on the high seas had choked off any news from home: “Two ships which have been taken by the French probably carried letters addressed to me.”

None of those lines ever reached their intended recipients. British warships instead snatched those letters, and scores more, from aboard merchant ships during wars from the 1650s to the early 19th century. . . .

Poorly sorted and only vaguely cataloged, the Prize Papers, as they became known, have now begun revealing lost treasures. Archivists at Britain’s National Archives and a research team at the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg in Germany are working on a joint project to sort, catalog, and digitize the collection, which gives a nuanced portrait of private lives, international commerce, and state power in an age of rising empires. The project, expected to last two decades, aims to make the collection of more than 160,000 letters and hundreds of thousands of other documents, written in at least 19 languages, freely available and easily searchable online. . . .

The full article is available here»

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From The Prize Papers Project:

The objects in the Prize Papers Collection were impounded by the High Court of Admiralty of the English and later British Royal Navy between 1652 and 1817, and they are now held by The National Archives of the UK.

The Prize Papers were collected a result of the early modern naval practice of prize-taking: capturing ships belonging to hostile powers, dealing severe blows to their military, political and economic capabilities. This practice had its heyday in the 17th and 18th centuries, and so the collection proves a fascinating insight into the formative period of European colonial expansion. . . .

The practice of prize-taking resulted in a vast, extraordinary and partly accidental archive of the early modern world, contains documents from more than 35,000 captured ships, held in around 4088 boxes and 71 printed volumes. The Prize Papers Collection includes at least 160,000 undelivered letters intercepted on their way across the seas, many of which remain unopened to this day. These are accompanied by books and papers on all manner of legal, commercial, maritime, colonial, and administrative matters, often embellished with notes and doodles. Documents in at least 19 different languages have been identified so far, and more languages are likely to be discovered as the project progresses. Alongside this written material is a variety of small miscellaneous artifacts, including jewelry, textiles, playing cards, and keys.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

In June 2022, the project published the first of the Prize Papers from the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48), with papers from ten French ships.

The project has a YouTube site with a handful of video presentations, including a fascinating session on letterlocking.

Reception of Greenough’s Statue of George Washington

Stereo card view of the crowd at the inauguration of Rutherford B. Hayes, on the east front grounds of the U.S. Capitol, surrounding Horatio Greenough’s statue of George Washington, in 1877 (Brady’s National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C./Library of Congress). Commissioned in 1832 to mark Washington’s 100th birthday, Horatio Greenough’s sculpture of the first president was installed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda in 1841. Two years later the 12-ton statue was moved outside to the building’s East Plaza, where it stood until 1908, when it was moved to the Smithsonian Institution castle on the National Mall.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

An interesting article from The Washington Post for the wider context of contested public sculpture (here presented for a large, general audience). Unfortunately, it doesn’t address this particular controversy in terms of people’s expectations of how a historic figure (in 1841, still a recent historic figure) should have been represented and thus might reinforce persistent misconceptions of nineteenth-century attitudes toward nudity in art generally. The larger question of monumentalizing the lives of real people could bring the history of Greenough’s work into conversation with the initial reception of Hank Willis Thomas’s recently installed memorial for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, The Embrace, at Boston’s 1965 Freedom Plaza. For the latter, there has, of course, been lots of coverage, but I like this article by Jessica Shearer, “What Do Bostonians Think of the New MLK Monument?,” HyperAllergic (25 January 2023). –CH

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Horatio Greenough, President George Washington, completed in 1840, marble (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution).

Ronald G. Shafer, “The First Statue Removed from the Capitol: George Washington in a Toga,” The Washington Post (22 January 2023).

Slowly, some of the U.S. Capitol’s many statues and other artworks honoring enslavers have been slated for removal, most recently a bust of Roger B. Taney, the chief justice who wrote the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision denying Black people citizenship. But the first statue Congress voted to remove from the Capitol was one of George Washington [in 1908]—not because Washington was an enslaver, but because the statue was scandalous. The first president was portrayed naked to the waist in a toga with his right finger pointing toward the sky and his left hand clasping a sheathed sword. . . .

The full article is available here»

Tallying Enslavers and Confederates Depicted at the U.S. Capitol

John Trumbull, General George Washington Resigning His Commission, 23 December 1783, installed in the Capitol in 1824, oil on canvas, 12 × 18 feet (Washington, DC: Capitol Rotunda). As noted in The Post article, 19 of the 31 people identified in the painting were enslavers.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From The Washington Post:

Gillian Brockell, “Art at Capitol Honors 141 Enslavers and 13 Confederates. Who Are They?,” The Washington Post (27 December 2022). The Post examined more than 400 statues, paintings, and other artworks in the U.S. Capitol. This is what we found.

As part of a year-long investigation into Congress’s relationship with slavery, The Washington Post analyzed more than 400 artworks in the U.S. Capitol building, from the Crypt to the ceiling of the Capitol Rotunda, and found that one-third honor enslavers or Confederates. Another six honor possible enslavers—people whose slaveholding status is in dispute. . . .

Just as governments and institutions across the country struggle with the complex and contradictory legacies of celebrated historical figures with troubling racial records, so too does any effort to catalogue the role of the Capitol artworks’ subjects in the institution of slavery. This analysis, for example, includes at least four enslavers—Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, Rufus King, and Bartolomé de las Casas—who voluntarily freed the people they enslaved and publicly disavowed slavery while they were living. Other people, such as Daniel Webster and Samuel Morse, were vocal defenders of slavery but did not themselves enslave people; artworks honoring them are not counted in The Post’s tally. . . .

All 11 states that joined the Confederacy have at least one statue depicting an enslaver or Confederate. But the homages to enslavers are by no means restricted to these states: Except for New Hampshire, all of the original 13 states have statues depicting enslavers or possible enslavers.

Massachusetts, for example, is represented by John Winthrop, who is best known for proclaiming a “shining city on a hill” but who also enslaved at least three Pequot people and, as colonial governor, helped legalize the enslavement of Africans.

Both of New York’s statues honor enslavers. One is Declaration of Independence co-writer Robert R. Livingston, who came from a prominent slave-trading family and personally enslaved 15 people in 1790. He also owned brothels that housed Black women who may have been enslaved. The other is former vice president George Clinton, who served under Jefferson and Madison and enslaved at least eight people in his lifetime. . . .

The full article is available here»

leave a comment