Call for Papers | Transforming Topography

From The Paul Mellon Centre:

Transforming Topography

The British Library, London, 6 May 2016

Proposals due by 30 September 2015

The British Library and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art are delighted to announce a call for papers for an international conference on transforming topography. The conference will be interdisciplinary in nature, and we invite contributions from art historians, architectural historians, map scholars, historians, cultural geographers, independent researchers, and museum professionals (including early-career) which contribute to current re-definitions of topography. We welcome contributions that engage with specific items from the British Library’s topographical collections and highlight the copious nuances that can be explored within topography, including, but not limited to:

The British Library and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art are delighted to announce a call for papers for an international conference on transforming topography. The conference will be interdisciplinary in nature, and we invite contributions from art historians, architectural historians, map scholars, historians, cultural geographers, independent researchers, and museum professionals (including early-career) which contribute to current re-definitions of topography. We welcome contributions that engage with specific items from the British Library’s topographical collections and highlight the copious nuances that can be explored within topography, including, but not limited to:

- Topography versus landscape: topography’s position within registers of pictorial representation

- Topography’s boundaries with other forms of knowledge, such as antiquarianism

- The role and identity of the artists and writers employed in producing topographical images and texts

- Topographic techniques and conventions, repetitions in text and image

- Patrons and collectors of topographical material: topography as a social and cultural practice, the circulation, use and display of these objects

- Topography and the library, museum or gallery

Topography is an emerging and dynamic field in historical scholarship. The Paul Sandby: Picturing Britain exhibition of 2009/2010 (Nottingham, Edinburgh, London) and subsequent research has sought a redefinition of topography. Rather than seeing topographical art as marginal compared to the landscapes in oils or watercolours by the canon of ‘great artists’ or more imaginative and Sublime images, a growing number of scholars are embracing the historical study of images of specific places in their original contexts, sparking a lively debate around nationhood, identity, and cultural value, or what John Barrell describes as “the conflict and coexistence of the various…’stakeholders’ in the landscape and in its representation” (Barrell, Edward Pugh of Ruthin, 2013).

The British Library holds the world’s most extensive and important collection of British topographic materials, including George III’s King’s Topographical Collection, currently being re-catalogued. There are hundreds of thousands of images and texts, including unique compilations of prints and drawings, rare first editions, maps, extra-illustrated books, and handwritten notes across the collections: all of which exhibit the broad range of forms and subject matter which topographical material can take. Using the BL’s main online catalogue and typing in ‘George III, views’ will give you a taste of what is available, as will the entry for the British Library in M.W. Barley’s A Guide to British Topographical Collections (1974). The majority of topographic materials are not listed individually, so if you need help finding specific items please contact Alice Rylance-Watson, Research Curator, at Alice.Rylance-Watson@bl.uk.

Please send proposals of no more than 300 words accompanied by a brief biography to: Ella Fleming, Events Manager, events@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk by 5.00pm on Wednesday 30 September 2015.

Exhibition | The Grand Trianon from Louis XIV to Charles de Gaulle

Now on view at Versailles (with the French press release available here)

The Grand Trianon from Louis XIV to Charles de Gaulle

Château de Versailles, 18 June — 8 November 2015

Curated by Jérémie Benoit

Until 8 November 2015, the Palace of Versailles is holding an exhibition that will trace the history of the Grand Trianon from its construction up to 1960. In 2016, another exhibition will show the modern era after the transformation of the Grand Trianon in a presidential palace by De Gaulle.

Until 8 November 2015, the Palace of Versailles is holding an exhibition that will trace the history of the Grand Trianon from its construction up to 1960. In 2016, another exhibition will show the modern era after the transformation of the Grand Trianon in a presidential palace by De Gaulle.

The Grand Trianon: A Private Palace for the Seat of Power

Situated in the north-west corner of the park of the Palace of Versailles, on land that once belonged to a village purchased by Louis XIV, the current Grand Trianon sits on the site of an initial palace built in 1670 by Louis Le Vau: the Porcelain Trianon. This small palace was designed mainly as a venue for the romantic relations between Louis XIV and the Marquise de Montespan, and got its name from the ‘Chinese-style’ blue and white porcelain that covered it.

It was destroyed in 1687 and replaced by the Marble Trianon, later called the Grand Trianon, which remains today. The building was the work of Jules Hardouin-Mansart and was given the name ‘Marble’ because of the Rance marble columns on the portico and the red Languedoc marble pilasters decorated with white Carrara marble capitals. The Grand Trianon was Louis XIV’s private estate and a palace for leisure, where he entertained the ladies of the court with shows and parties. It has retained its 17th-century decoration, wood panelling and paintings depicting the Metamorphoses of Ovid, in perfect harmony with the light ambience of this country house.

The Grand Trianon was relatively little used by Louis XV, who nevertheless spent a while living there with the Marquise de Pompadour. During the French Revolution its collections were dispersed. In 1804 it became the Imperial Palace, when Napoleon restored its lustre and fully refurnished it for his marriage with the Empress Marie-Louise. The palace was inhabited for the last time by King Louis-Philippe, who housed his entire family there and somewhat modified the building to make it more comfortable.

It was turned into a museum at the end of the 19th century and filled with various motley objects, and it was only in the 20th century that the Grand Trianon regained its splendour and historical furnishings. Most recently, the birth of the French 5th Republic constituted a turning point for this estate, transforming it into a presidential residence destined to host foreign Heads of State.

The Exhibition

A collection of plans, engravings and drawings reveal the modifications and changes made to the Grand Trianon over the course of history. Painted masterpieces from Trianon, commissioned in 1688 by Louis XIV or in 1811 by Napoleon, and portraits of those who lived in the Palace recreate the atmosphere of smaller rooms centred around furniture designed for intimacy, like for example the Emperor’s pedestal surrounded by the chairs from the Hall of Mirrors, or the chair belonging to Princess Clémentine d’Orléans, the daughter of Louis-Philippe. Fascinating objects such as the recently restored ivory kiosk by Barrau and the vase of the Imperial Hunt by Swebach embellish the exhibition.

Chaise du salon des Glaces, Jacob-Desmalter, c. 1805, ivoire, ébène, buis, bois précieux divers (Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon)

Three desk chairs very similar in form are spread throughout the exhibition: two were used by Napoleon and the third belonged to General De Gaulle. They are symbolic of the permanent presence of power in the palace of Trianon and forerun the second part of the exhibition that will be held in 2016, and will be devoted to the history of the Grand Trianon from 1960 to today.

During the 1960s and thanks to André Malraux, Minister for Culture at the time, General de Gaulle decided to launch an extensive programme to renovate the palace in terms of its historical furnishings, aiming to transform it into a presidential residence for the needs of the French 5th Republic. The future exhibition will use various items and memories from the first President of the 5th Republic to review the major role played by Trianon in international relations.

From the 1960s to the 1990s the palace, which at the time hosted visitors to France in one wing, and housed the French President in Trianon-sous-Bois, was the location of grand and sumptuous receptions. After many years, in 2014, the tradition was renewed when the President of the Republic François Hollande received the President of the People’s Republic of China, Xi Jinping, for a private dinner.

The Burlington Magazine, July 2015

The eighteenth century in The Burlington:

The Burlington Magazine 157 (July 2015)

A R T I C L E S

A R T I C L E S

• Peter Lindfield, “New Light on Chippendale at Hestercombe House,” pp. 452–56.

• Susan Owens, “A Note on Jonathan Richardson’s Working Methods,” pp. 457–59.

• Peter Moore and Hayley Flynn, “John Collett’s Temple Bar and the Discovery of a Preparatory Study,” pp. 460–64.

• Alycen Mitchell and Barbara Pezzini, “‘Blown into Glittering by the Popular Breath’: The Relationship between George Romney’s Critical Reputation and the Art Market,” pp. 465–73.

R E V I E W S

• Charles Truman, Review of Gerhard Röbbig, ed., Meissen Snuffboxes of the Eighteenth Century (Hirmer Verlag, 2013), p. 484.

• Maureen Cassidy-Geiger, Review of Haydn Williams, Turquerie: An Eighteenth-Century European Fantasy (Thames & Hudson, 2014), p. 487.

• J.V., Review of Ian Warrell, Turner’s Sketchbooks (Tate Publishing, 2014), p. 488.

• Robert O’Byrne, Review of the exhibition, Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690–1840, p. 509–10.

Exhibition | Fragonard’s Enterprise

Now on view at the Norton Simon:

Fragonard’s Enterprise: The Artist and the Literature of Travel

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, 17 July 2015 — 4 January 2016

Curated by Gloria Williams Sander

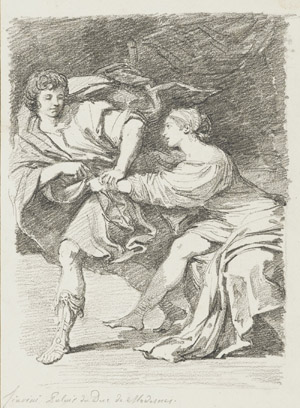

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Study after Lionello Spada: Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (from the Palazzo Ducale, Modena), 1760–61, 18 x 13 inches (45 x 33 cm (Pasadena: Norton Simon Museum)

Before Jean-Honoré Fragonard ascended to the rank of one of the 18th century’s most popular painters, he studied at the French Academy in Rome, where he practiced the fundamental art of drawing as a method to hone his skills and to establish his own unique style. In Rome, he encountered his first patron, Jean-Claude Richard de Saint-Non (1727–1791). A passionate advocate of the arts, Saint-Non was an eager participant in the Grand Tour, the educational pilgrimage to Italy then in vogue throughout Europe. His voyage, made from 1759 to 1761, inspired him to chronicle this experience for an audience that shared his fascination with the peninsula. Saint-Non invited the young Fragonard to join in his tour through Italy’s illustrious cities. In exchange, Fragonard was tasked with making copies after the important paintings and monuments seen in the churches and palazzi. The black chalk drawings Fragonard produced for his sponsor served as source material for Saint-Non’s engravings and aquatints, which were published in suites, and in his illustrated travel book Voyage de Naples et de Sicile (1781–86). These immensely popular publications served as barometers of taste for the arts and as beloved reminders of the masterpieces visited.

Enthusiasm for classical antiquity and Neapolitan Baroque painting drew many tourists to Naples. Saint-Non enjoyed multiple visits to the city, and during Fragonard’s visit in March 1761, he created inspired copies after the masterpieces he visited in private and public spaces. Occasionally he combined subjects from different locations on one sheet of paper. St. Luke Surrounded by Angels, for example, was copied from a fresco by Giovanni Lanfranco in the Church of the Holy Apostles. On the same sheet, Fragonard flanked Luke’s figure with two prophets (Daniel and Habakkuk?) that caught his attention at the Certosa di San Martino, painted by the Spaniard Jusepe de Ribera. The result of this imaginative pastiche is so fluid that few would suspect it was a combination drawing.

With its sunlit canals and magnificent architecture, Venice proved irresistible to the Grand Tourist. Fragonard and Saint-Non passed more than a month there. Inspired by Titian, Tintoretto and Veronese, the French artist produced lively, free-spirited copies, as evidenced in his Study after Paolo Veronese’s Adoration of the Magi, 1582, from the Church of San Nicolò della Lattuga ai Frari. Fragonard shifted Veronese’s vertical format to a horizontal one, and deemphasized the architecture to concentrate on the rhythmic interweaving of the figures that he must have admired in the original.

The Norton Simon Museum owns 139 of the almost 300 drawings produced by Fragonard during this journey with his patron and friend. Approximately 60 drawings document their voyage to see the great artistic treasures of Florence, Bologna, and Padua, among other cities. Fragonard’s Enterprise explores the excitement of this expedition, the documentary and practical value of the drawings, as well as their history following publication, especially as they were treasured by later collectors.

Exhibition | A Revolution of the Palette

Now on view at the Norton Simon:

A Revolution of the Palette: The First Synthetic Blues and Their Impact on French Artists

Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, 17 July 2015 — 4 January 2016

Curated by John Griswold

The accidental discovery of Prussian blue in an alchemist’s laboratory around 1704 helped to open up new possibilities for artistic expression at the dawn of the Enlightenment. A Revolution of the Palette explores the use of this pigment, followed by the introduction of cobalt blue and synthetic ultramarine, by French artists from the Rococo period to the threshold of Impressionism.

Marie-Louise-Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Portrait of Theresa, Countess Kinsky,1793, oil on canvas, 54 x 39 inches, 138 x 100 cm (Pasadena: Norton Simon Art Foundation)

A new palette available to artists, thanks largely to the addition of Prussian blue in the 18th century, helped fuel the heated philosophical debates regarding Newtonian color theory. The fascinating new capabilities of artists to exploit sophisticated color relationships based on scientific optical principles became a core precept of Rococo painting, or peinture moderne as it was called at the time. Exquisite examples of the early use of Prussian blue by Fragonard and his immediate circle demonstrate their technical achievements. Paintings by Vigée-Lebrun, Prud’hon and Ingres show the masterful use of Prussian blue as Neoclassicism took hold. The sophisticated, subtle manipulations of color in academic painting of the period, exemplified by Ducis’ Sappho Recalled to Life by the Charm of Music and Degas’ early and ambitious emulation of a Poussin composition, The Rape of the Sabines, rely heavily on the ability of the new blues to deftly modulate tone and hue in ways never available to earlier painters.

As revolutionary as this new blue color proved to be, Prussian blue was a mere precursor to the explosion of available colors brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, the French government played an active role in catalyzing innovation at the dawn of the 19th century, as the country emerged from the Revolution with its economy in disarray. Chemist Louis Jacques Thénard’s development of the next synthetic blue, a vivid cobalt blue pigment, was inspired by the traditional cobalt oxide blue glazes seen on 18th-century Sèvres porcelain. An exquisite lidded vase on loan from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens illustrates this.

The third synthetic blue to emerge was the culmination of centuries of searching for a cheap, plentiful, high-quality replacement for the most valuable of all pigments: natural ultramarine. This was a color derived from lapis lazuli, a rare, semiprecious gemstone mined almost exclusively in Afghanistan since the 6th century, and imported to Europe through Venice. It is famously known to have been more costly than gold during the Renaissance. Natural ultramarine provided a brilliant, royal blue hue, but only if coarsely ground and applied in a comparatively translucent glaze over a light-reflecting ground. Other blue colors, such as smalt, which was essentially composed of particles of colored glass, were available to help achieve the lovely hues of ultramarine, but the poor covering ability of the paint and the difficulty of its preparation and use were familiar limitations.

In 1824, the French government announced a competition among chemists to develop a true synthetic ultramarine. The prize was finally awarded in 1828 to Jean-Baptiste Guimet. Painters at last had an affordable, fully balanced palette of cool and warm colors spanning the full spectrum. This fact, combined with the innovation of ready-mixed tube oil colors, greatly facilitated the direct representation of nature. The ability of painters to capture a wide range of observed natural effects in the landscape en plein air are represented by the works of Corot, Guigou, Monticelli and Dupré. A Revolution of the Palette closes with two canvases representing the Impressionists’ full realization of the wide-open possibilities made possible by these new blues: Guillaumin’s The Seine at Charenton (formerly Daybreak), and Caillebotte’s Canoe on the Yerres River.

Exhibition | An Elegant Society: Adam Buck, Artist in the Age of Austen

Adam Buck, First Steps, 1808. Watercolour, 28 x 35 cm

(Private Collection)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Press release (23 April 2015) from the Ashmolean:

An Elegant Society: Adam Buck, Artist in the Age of Jane Austen

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 16 July — 4 October 2015

Crawford Art Gallery, Cork, 4 February — 9 April 2016

Curated by Peter Darvall

Well-known to collectors and Jane Austen enthusiasts, Irish artist Adam Buck (1759–1833) was one of Regency England’s most sought-after portrait painters. He worked in Ireland for twenty years, becoming an accomplished miniaturist; but moved to London in 1795 and immediately gained a roster of star clients including the Duke of York and his scandalous mistress, Mary Anne Clarke. This summer exhibition celebrates Adam Buck’s influence on Georgian art and style, showing over sixty works from private collections including watercolours, small portraits and miniatures, examples of his decorative designs for porcelain and fans, and his prints.

Buck was born to a family of silversmiths in Cork, the second of four surviving children. His younger brother, Frederick (1765–1840), became an established miniature painter who worked in Cork his entire life. Details of Adam’s career before he moved to London are elusive, but his early work is in many ways that of the quintessential Regency miniaturist. His first known pictures, dating from the late-1770s to the early-1780s, show an innate appreciation of the established Neoclassical style: his sitters are often shown in profile; their gowns styled like Grecian goddesses; group portraits arranged like a frieze. In emigrating to London in 1795, Buck took the route of many fellow Irishmen including several Cork-born artists and writers such as James Barry (1741–1806) and Alexander Pope (1759–1847). Buck’s first London home was in Piccadilly. As soon as he arrived, he began to exhibit at the Royal Academy where he showed a surprising total of 179 works over the following 38 years.

Buck was born to a family of silversmiths in Cork, the second of four surviving children. His younger brother, Frederick (1765–1840), became an established miniature painter who worked in Cork his entire life. Details of Adam’s career before he moved to London are elusive, but his early work is in many ways that of the quintessential Regency miniaturist. His first known pictures, dating from the late-1770s to the early-1780s, show an innate appreciation of the established Neoclassical style: his sitters are often shown in profile; their gowns styled like Grecian goddesses; group portraits arranged like a frieze. In emigrating to London in 1795, Buck took the route of many fellow Irishmen including several Cork-born artists and writers such as James Barry (1741–1806) and Alexander Pope (1759–1847). Buck’s first London home was in Piccadilly. As soon as he arrived, he began to exhibit at the Royal Academy where he showed a surprising total of 179 works over the following 38 years.

His success as a society artist was almost instant. By 1799 he had executed a full-length portrait of the Prince of Wales in his Garter Robes. He exhibited two portraits of Prince Frederick, Duke of York, at the Royal Academy in 1804 and 1812. Buck was also introduced to Mary Anne Clarke (1776–1852), the most celebrated of the Duke’s well-known mistresses. She was a famous beauty and maintained a fabulous household in London, subsidising her extravagant lifestyle by selling her influence with the Duke who was Commander in Chief of the Army. Rumours claiming that she could obtain commissions and appointments for a fee culminated in a parliamentary enquiry into the Duke’s conduct. While the Duke was ridiculed in caricatures and lampoons, Mary Anne, who put up a spirited defence of her role in the affair, became a public heroine. Her image was circulated in flattering portraits by Buck and other artists which were engraved and widely published. In 1813 she finally overreached herself and was imprisoned for nine months for libel, before leaving the country for Boulogne where she died in 1852.

Buck’s work was made popular largely through prints after his watercolours, chiefly published in London by William Holland and Rudolph Ackermann. His images, refined and elegant, contrasted with the savage caricatures and ribald pictures of contemporary artists like James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank. The difference was humorously summed up in a Thomas Rowlandson print with the title, Buck’s Beauty and Rowlandson’s Connoisseur (1800), in which a rake in wig and frock coat, one of Rowlandson’s stock characters, leers through an eye-glass at a demure, pink-cheeked girl, drawn in Buck’s distinctive manner. With his name made in association with the colourful ranks of Regency society, Buck, from 1810 onwards, made a new reputation for himself with his sentimental images of women and children under titles such as The First Steps in Life and Mother’s Hope. By 1829 his work had been reproduced by at least twenty-eight different printmakers in England and by several in France and America.

Peter Darvall, Guest Curator, says: “I hope, with this exhibition and monograph on Adam Buck’s work, to bring his art to the attention of a wider audience. Buck was a hugely influential artist during his own time and his elegant portraits of royalty and officers, and his charming illustrations of Georgian life and manners have had an enduring impact on the popular imagination of Regency society.”

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the Ashmolean shop:

Peter Darvall and Jon Whiteley, Adam Buck, 1759–1833 (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum Publications, 2015), 192 pages, ISBN: 978-1910807002, £20.

Adam Buck (1759–1833) was an Irish portrait painter, print-maker and miniaturist from Cork who migrated to London c.1795. His name is well-known to collectors and historians of British prints and watercolours and for many years his work has appeared regularly in sale catalogues. And yet, while there have been a few short articles published on his contribution to print-making, ceramic decoration and the study of Greek vases, it is surprising that no serious attempt has previously been made to collate the little that is known about his life and work. Moreover, he has never been the subject of a monographic exhibition apart from one at the Leicester Gallery in 1925 and, more recently, a small exhibition at the Cynthia O’Connor Gallery in Dublin in 1984 and another at the Alpine Gallery in London, mounted by Andrew Kimpton, in 1989.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Note (added 6 February 2015) — At the Crawford Art Gallery, a distilled version of the show is entitled Adam Buck: A Regency Artist from Cork.

Exhibition | Yo, el Rey: La Monarquía Hispànica en el arte

The exhibition press release, via Art Daily (13 July 2015) . . .

Yo, el Rey: La Monarquía Hispànica en el arte

Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City, 1 July — 18 October 2015

Curated by Abraham Villavicencio

The Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (INBA) presents the exhibition Yo, el Rey. La Monarquía Hispànica en el arte, curated and produced by the Museo Nacional de Arte. This is a comprehensive exhibit that offers the audience, through national and international masterpieces, a review of the figure of the Hispanic sovereign. The exhibition approaches the mechanisms and representation forms of the monarch with a selection of 200 works, amongst which are paintings, drawings, sculptures, textiles, jewelry, silverware, armors and historic documents.

The Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (INBA) presents the exhibition Yo, el Rey. La Monarquía Hispànica en el arte, curated and produced by the Museo Nacional de Arte. This is a comprehensive exhibit that offers the audience, through national and international masterpieces, a review of the figure of the Hispanic sovereign. The exhibition approaches the mechanisms and representation forms of the monarch with a selection of 200 works, amongst which are paintings, drawings, sculptures, textiles, jewelry, silverware, armors and historic documents.

Important international loans have been obtained through the leadership and management of the Museo Nacional de Arte, which come from the Museo Nacional del Prado, Colecciones Reales del Patrimonio Nacional, Museo de América, and Museo Lázaro Galdiano, from Spain; and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Hispanic Society of America and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, from the United States, as well as national collections, such as the National Museum of Art of San Carlos, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Museo Franz Mayer, and Museo Regional de Querétaro. It also has the invaluable participation of religious institutions: Catedral de Sevilla, Catedral Metropolitana de la Cuidad de México, Templo de San Felipe Neri La Profesa, Museo de la Basílica de Guadalupe and more than 20 private collections.

It is important to address the decisive contribution of the Museo Nacional de Arte to the conservation of our national patrimony, because thanks to this exhibition many pieces have been restored in benefit of a better preservation of novohispanic pieces, among them the Retrato de Carlos III from Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz.

The exhibition, which was curated by Abraham Villavicencio, Vice-royalty Art curator of the Museo Nacional de Arte, is developed in four thematic cores that revolve around the King as a unifying figure of the American kingdoms, and a vast politic system known as the Hispanic Monarchy.

La herencia iconográfica del pasado antiguo refers to the significance of the founding myths of royalty and kingdom, showing how, through symbolic elements of the Roman, Indigenous and German past, the image of the Hispanic monarch was built.

La efigie real. Recursos plásticos y retóricos suggests the constitution of the sovereign’s body image through attributes denoting power, which enhance the idea of authority among the royal houses of the Spanish Empire: the Habsburgo and the Borbón.

The third core, La monarquía mesiánica y el imaginario religioso, explores the king’s performance as patron of the church through his representation and the narrow link between the state and ecclesiastic institutions.

The exhibition closes with Ecos de la monarquía en el México independiente, in which the figures of Fernando VII, Agustín de Iturbide, and Maximiliano I of Mexico appear as witnesses of the survival of the mythic, politic and religious imageries of the viceroyalty of the Nueva España, even in the independent Mexico.

Jean Ranc Carlos de Borbón y Farnesio, niño (futuro Carlos III de España), hacia 1724. Óleo sobre lienzo. 145.5×116.5cm (Madrid: Prado)

According to Agustín Arteaga, director of the Museo Nacional de Arte, “the topic acquires a new vitality when being presented as an exhibition, not only for the scholars of the viceroyalty but for everyone who wants to familiarize himself with the works that are a part of the . . . past in which an empire, with particular forces and dynamics, was constituted.”

The exhibition articulates the development of political and juridical elements which visitors will be able to appreciate as a rich heritage that seeks to value the Hispanic, novo Hispanic, and Mexican creators as a group with the same political and cultural identity. Therefore, under the same curatorial speech, pieces from some of the most recognized European painters of the XVI and XVII centuries—the Siglo de Oro—up to the XIX century are reunited: Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Goya, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Francisco de Zubarán and Jean Ranc, with renowned novo Hispanic and Mexican artists, such as Cristóbal de Villalpando, Juan Correa, Baltasar de Echave Orio, Manuel Tolsá, Santiago Rebull and Felipe Sojo, amongst others.

The exhibition catalogue, with a bilingual edition, conjugates texts of six specialists from the Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, the Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the Colegio de México, the Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia, the Museo Nacional del Virreinato, and the Museo Nacional de Arte. The publication addresses political, legal, iconographical, and theological dimensions, besides making the historical and artistic transformations obvious with approximately 200 color illustrated pieces that narrate the construction of the image of the Hispanic monarch in the Indias. In addition, all the texts of the exhibit rooms will be displayed in English and Spanish.

The Museo Nacional de Arte recognizes and appreciates the support of: El Patronato del Museo Nacional de Arte, Amigos MUNAL Arte Mexicano: Promoción y Excelencia AC, Iberdrola, British Airways-Iberia, and NH Hotels for the efforts made towards the creation of new projects.

The Sound of Paris in the Eighteenth Century

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Audio Reconstruction of Eighteenth-Century Paris

A team from Université Lyon-2, led by Mylène Pardoen (Department of Music and Musicology), has reconstructed the soundscape of eighteenth-century Paris.

From Le Journal CNRS (Centre national de la recherche scientifique). . .

La musicologue Mylène Pardoen a reconstitué l’ambiance sonore du quartier du Grand Châtelet à Paris, au XVIIIe siècle. Présenté au salon de la valorisation en sciences humaines et sociales, à la Cité des sciences et de l’industrie, son projet associe historiens et spécialistes de la 3D.

Paris comme vous ne l’avez jamais entendu ! C’est l’expérience que propose la musicologue Mylène Pardoen, du laboratoire Passages XX-XXI, à travers le projet Bretez. Un nom qui n’a pas été choisi par hasard : la première reconstitution historique sonore conçue par ce collectif associant historiens, sociologues et spécialistes de la 3D1, a en effet pour décor le Paris du XVIIIe siècle cartographié par le célèbre plan Turgot-Bretez de 1739 – Turgot, prévost des marchands de Paris, en étant le commanditaire, et Bretez, l’ingénieur chargé du relevé des rues et immeubles de la capitale.

70 tableaux sonores

C’est plus précisément dans le quartier du Grand Châtelet, entre le pont au Change et le pont Notre-Dame, que la vidéo de 8 minutes 30 transporte le visiteur. « J’ai choisi ce quartier car il concentre 80 % des ambiances sonores du Paris de l’époque, raconte Mylène Pardoen. Que ce soit à travers les activités qu’on y trouve – marchands, artisans, bateliers, lavandières des bords de Seine… –, ou par la diversité des acoustiques possibles, comme l’écho qui se fait entendre sous un pont ou un passage couvert… » S’il existe déjà des vidéos sonorisées, c’est la première fois qu’une reconstitution en 3D est bâtie autour de l’ambiance sonore : les hauteurs des bâtiments comme les matériaux dans lesquels ils sont construits, torchis ou pierre, tiennent compte des sons perçus – étouffés, amplifiés… – et inversement. . . .

More information is available here»

Conference | Sculpture and Parisian Decorative Arts in Europe

From H-ArtHist:

The Role of Sculpture in the Design, Production, Collecting,

and Display of Parisian Decorative Arts in Europe, 1715–1815

Mons, Belgium, 29 August 2015

An international conference on the occasion of Mons European Capital of Culture 2015 and Waterloo 1815–2015 on Saturday, 29 August 2015

Between 1715 and 1830 Paris gradually became the capital of Europe, “a city of power and pleasure, a magnet for people of all nationalities that exerted an influence far beyond the reaches of France,” as Philip Mansel wrote, or as Prince Metternich phrased it, “When Paris sneezes, Europe catches cold.” Within this historical framework and in a time of profound societal change, the consumption and appreciation of luxury goods reached a peak in Paris. The focus of this one-day international conference will be the role of the sculptor in the design and production processes of Parisian decorative arts—from large-scale furniture and interior decoration projects to porcelain, silver, gilt bronzes, and clocks.

In the last few years a number of studies were carried out under the auspices of decorative arts museums and societies such as the Furniture History Society and the French Porcelain Society. It now seems appropriate to bring some of these together to encourage cross-disciplinary approaches on a European level and discussion between all those interested in the materiality and the three-dimensionality of their objects of study. The relationships between, on the one hand, architects, ornemanistes and other designers, and on the other sculptors, menuisiers, ébénistes, goldsmiths, porcelain manufacturers, bronze casters, and other producers, as well as the marchands merciers, will be at the heart of the studies about the design processes.

A second layer of understanding of the importance of sculpture in the decorative arts will be shown in the collecting and display in European capitals in subsequent generations, particularly those immediately after the French Revolution, as epitomised by King George IV. Overall, the intention of this conference is to shed light on the sculptural aspect of decorative arts produced in Paris in the long 18th century and collected and displayed in the capitals of Europe. Without pretending to be exhaustive, this study day—and its publication—hopes to bring together discussions about the histories and methodologies that could lead to furthering the study of hitherto all too often neglected aspects of the decorative arts.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

S A T U R D A Y , 2 9 A U G U S T 2 0 1 5

Maison de la Mémoire de Mons, ancien couvent des Sœurs Noires, rue des Sœurs Noires 2, accessible via the porch on rue du Grand Trou Oudart, Mons

9.00 Registration and coffee

9.45 Welcome and introduction by Jean Schils/Werner Oechslin/Léon Lock

10.00 Session 1: Sculpture as a theme / sculpture as an object, within French decorative arts

Chair: Guilhem Scherf, Musée du Louvre, Paris

• Luca Raschèr, Koller Auktionen, Zürich, Humanité et bestiaire en bronze sur les meubles français du XVIIIe siècle

• Charles Avery, Cambridge, An elephantine rivalry: The ménagerie clocks of Saint-Germain and Caffiéri

• Virginie Desrante, Cité de la Céramique, Sèvres, Petite sculpture et objets de luxe, le biscuit de Sèvres: Une révolution esthétique

• Xavier Duquenne, Brussels, Le sculpteur de la cour Augustin Ollivier, de Marseille, au Palais de Charles de Lorraine à Bruxelles

12.15 Lunch

13.15 Session 2: The role of the sculptor within the design and production processes

• Jean-Dominique Augarde, Centre de Recherches Historiques sur les Maîtres Ébénistes, Paris, De Houdon à Prud’hon, la collaboration entre sculpteurs et bronziers d’ameublement de 1760 à 1820

• Audrey Gay-Mazuel, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, Du dessin au montage, les sculpteurs dans l’atelier de l’orfèvre parisien Jean-Baptiste-Claude Odiot (1763–1850)

• Jean-Baptiste Corne, Ecole du Louvre/Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris, Le sculpteur ornemaniste à la veille de la Révolution. Une condition sociale en mutation?

15.00 Coffee

15.30 Session 3: French sculptural decorative arts in international perspective

Chair: Werner Oechslin, ETH Zürich/ SBWO Einsiedeln

• Léon Lock, University of Leuven, Comment la rocaille parisienne conquit Munich: Le rôle de l’architecte et ornemaniste François Cuvilliés (Soignies 1695–Munich 1768)

• Guido Jan Bral, Brussels, Les ducs d’Arenberg, mécènes des arts décoratifs parisiens à Bruxelles (1765–1820)

• Timothy Clifford, Former Director, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, Title to be confirmed.

16.55 Conclusions and discussion

17.15 Reception

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Registration

Free for members of the Low Countries Sculpture Society and of the Maison de la Mémoire of Mons, but registration compulsory: info@lcsculpture.org. Seating is limited so book early to avoid disappointment. Non-members €25 per person.

Optional Lunch

Full sit-down on-site lunch €25 per person, to be booked and paid in advance. Closing date for lunch applications and payments: Wednesday 26 August 2015 at 12 noon.

Hotel Accommodation and Travel from Paris

Hotel rooms have been pre-booked for foreign participants. Anyone wishing to take over these reservations, please contact us. A limited number of train tickets from Paris to Valenciennes and back (with transfer by car to/from Mons) is also available.

Payments

By bank transfer or by credit card (details/forms available on request)

Gala Evening on Friday, 28 August

Those who register for the international conference, will receive an invitation to attend the Gala Evening organised the night before in a spectacular country house not far from Mons. This evening will see the launch of the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Library Appeal.

Exhibition | Scottish Artists 1750–1900: From Caledonia to the Continent

Press release (5 May 2015) from the Royal Collection Trust:

Scottish Artists 1750–1900: From Caledonia to the Continent

The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, 6 August 2015 — 7 February 2016

The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London, 18 March — 9 October 2016

Allan Ramsay, Queen Charlotte with her two Eldest Sons, ca. 1764-69 (London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 404922)

From the romantic landscapes of Caledonia to exotic scenes from the Continent, a new exhibition at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse is the first dedicated to Scottish art in the Royal Collection. Bringing together over 80 works, including paintings and drawings by the celebrated artists Allan Ramsay and Sir David Wilkie, Scottish Artists 1750–1900: From Caledonia to the Continent tells the story of royal patronage and of the emergence of a distinctive Scottish school of art.

Allan Ramsay (1713–1784) was the first Scottish artist of European significance. A pre-eminent figure of the Enlightenment, the intellectual movement that swept across Europe in the 18th century, Ramsay maintained close friendships with philosophers such as David Hume and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. In 1760 he was commissioned to paint George III’s State portrait and subsequently became the first Scot to be appointed to the role of Principal Painter in Ordinary to His Majesty. Depicting the King in sumptuous coronation robes and breeches of cloth of gold, Ramsay produced the definitive image of George III and the most frequently copied royal portrait of all time.

Ramsay worked as a court artist, painting members of the royal family and producing copies of the coronation portrait for the King to send as gifts to ambassadors and governors. He enjoyed a good relationship with the Queen Consort, and his painting Queen Charlotte and her Two Eldest Sons, 1764, considered to be among Ramsay’s greatest works, combines the grandeur of a royal portrait with the intimacy of a domestic scene.

Over half a century later, Fife-born artist Sir David Wilkie (1785–1841) gained even wider recognition than Ramsay. His vivid, small-scale scenes of everyday life, inspired by those of the Dutch masters, were shown at the Royal Academy to great acclaim. Wilkie attracted the attention of the Prince Regent (the future George IV), who was acquiring 17th-century Dutch and Flemish genre paintings for his own collection. The artist’s reputation was sealed with two high-profile royal commissions – Blind-Man’s-Buff, 1812, and The Penny Wedding, 1818, which shows the uniquely Scottish custom of wedding guests contributing a penny towards the cost of the festivities and a home for the newly married couple.

George IV’s visit to Scotland in 1822, the first by a reigning British monarch for nearly two centuries, offered a major opportunity for royal patronage. Artists were given prime access to all of the events in the two-week programme, which was masterminded by the writer Sir Walter Scott. The entrance of the King to his Scottish residence is captured in Wilkie’s The Entrance of George IV to Holyroodhouse, 1822–30. The King is shown being presented with the keys to the Palace, while crowds of enthusiastic spectators clamber over every part of the building to see him.

After suffering a nervous breakdown, brought on by overwork and a series of family tragedies, Wilkie set off on a prolonged visit to the Continent. He was one of the first professional artists to visit Spain after the Spanish War of Independence of 1808–14. Wilkie’s travels proved to be a turning point in his art, which became much broader in style and took inspiration from contemporary events. On the artist’s return in 1828, the King summoned Wilkie to Windsor and purchased five continental pictures—A Roman Princess Washing the Feet of Pilgrims, 1827, I Pifferari, 1827, The Defence of Saragossa, 1828, The Spanish Posada, 1828, and The Guerilla’s Departure, 1828—and commissioned The Guerilla’s Return, 1830. The same year, the King appointed Wilkie to the position of Principal Painter in Ordinary, a post that the artist continued to hold under William IV and Queen Victoria.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert saw their roles as patrons of the arts as part of the duty of Monarchy. Several pictures by Scottish artists were among the birthday and Christmas presents exchanged by the royal couple throughout their married life, including works by Sir Joseph Noël Paton (1821–1901), David Roberts (1796–1864), James Giles (1801–1870) and John Phillip (1817–1867). Queen Victoria had a deep love of Scotland and commissioned artists to record the country’s ‘inexpressibly beautiful’ scenery, including that of her recently acquired estate, Balmoral, in the Highlands. Among those artists was the Glaswegian William Leighton Leitch (1804–1883), who was appointed the Queen’s drawing master in 1846. Of all the Scottish artists whose work was collected by Victoria and Albert, it was William Dyce who was most in tune with Prince Albert’s tastes. Dyce was inspired by the early Italian art so admired by Albert, who purchased Dyce’s The Madonna and Child, 1845, and the following year commissioned a companion picture, St Joseph.

In the same period, the publication of travel books and growing interest in foreign cultures encouraged artists to seek inspiration abroad. David Roberts introduced British audiences to scenes of Egypt and the Holy Land, and was the first independent professional artist to travel extensively in the Middle East. A View of Cairo, 1840, shows the medieval Gate of Zuweyleh, and was one of Roberts’ first paintings of the region to be exhibited. Queen Victoria commissioned two Spanish pictures from Roberts as gifts for Prince Albert: A View of Toledo and the River Tagus, 1841, and The Fountain on the Prado, Madrid, 1841.

In the mid-19th century, there was a growing interest in Spanish culture, which was heavily romanticised in the literature of the day. When the artist John Phillip travelled to the country, his subject-matter changed from Scottish rural scenes to Spanish street life. Queen Victoria commissioned Phillip’s A Spanish Gypsy Mother, 1852, and purchased ‘El Paseo’, 1854, for Prince Albert. The Prince gave the Queen The Letter Writer of Seville, 1854, for Christmas. After a visit to the Royal Academy in 1858, Victoria acquired The Dying Contrabandista as a Christmas gift for the Prince that year. John Phillip was Queen Victoria’s favourite Scottish artist and, on his death in 1867, he was mourned by the monarch as ‘our greatest painter’.

Some notable Scottish works entered the Royal Collection in 1888, on the occasion of the opening of the Glasgow International Exhibition of Science, Art and Industry by the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII). This exhibition, held in Kelvingrove Park, was one of a series of international exhibitions and world fairs that dominated the cultural scene in the second half of the 19th century and the largest to be held in Scotland. The Prince and Princess of Wales were presented with ‘two elegant albums of paintings by members of the Glasgow Art Club’, including work by the Glasgow Boys: Sir James Guthrie (1859–1930), EA Walton (1860–1922) and Robert Macaulay Stevenson (1860–1952).

Scottish Artists 1750–1900: From Caledonia to the Continent is part of the Edinburgh Art Festival.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Distributed in the U.S. by The University of Chicago Press:

Deborah Clarke and Vanessa Remington, Scottish Artists 1750–1900: From Caledonia to the Continent (London: Royal Collection Trust, 2015), 210 pages, ISBN: 978-1909741201, $25.

Throughout its history, Scotland has produced a wealth of great works of art, and the Scottish Enlightenment in particular provided a powerful impetus for new forms of art and new artistic subjects. This survey of Scottish art in the Royal Collection brings together more than one hundred reproductions of works from the Enlightenment to the twentieth century to highlight the importance and influence of this period, while also sharing recent research on the subject.

Throughout its history, Scotland has produced a wealth of great works of art, and the Scottish Enlightenment in particular provided a powerful impetus for new forms of art and new artistic subjects. This survey of Scottish art in the Royal Collection brings together more than one hundred reproductions of works from the Enlightenment to the twentieth century to highlight the importance and influence of this period, while also sharing recent research on the subject.

The first book devoted to Scottish art in the Royal Collection, Scottish Artists fully explores this rich artistic tradition, incorporating discussions of artists whose inspiration remained firmly rooted in their native land, such as Alexander Nasmyth and James Giles, as well as artists who were born in Scotland and traveled abroad, from the eighteenth-century portraitist Allan Ramsay to David Wilkie, who traveled to London and is well-known for his paintings portraying everyday life. Broadly chronological, the book also traces the royal patronage of Scottish artists throughout the centuries, including works collected by monarchs from George III to Queen Victoria, and the official roles, Royal Limner for Scotland and King’s Painter in Ordinary.

leave a comment