New Book | The Beauty of Time

From Rizzoli:

François Chaille and Dominique Fléchon, The Beauty of Time (Paris: Flammarion, 2018), 280 pages, ISBN: 978-2080203410, $85.

Published in partnership with the prestigious Fondation Internationale de la Haute Horlogerie, this book presents the most beautiful timepieces from the Middle Ages to the present. Lavishly illustrated, The Beauty of Time contains a selection of nearly two hundred wonders—from mechanical and pendulum clocks to pocket and wristwatches. The timepieces are annotated by an expert horology historian and accompanied by a text that elucidates the cultural and artistic contexts in which they were created. As a counterpoint to the timepieces, extensive reproductions of artistic masterpieces provide perspective regarding the technical advances of each period and demonstrate the evolution of aesthetic tastes over time.

Published in partnership with the prestigious Fondation Internationale de la Haute Horlogerie, this book presents the most beautiful timepieces from the Middle Ages to the present. Lavishly illustrated, The Beauty of Time contains a selection of nearly two hundred wonders—from mechanical and pendulum clocks to pocket and wristwatches. The timepieces are annotated by an expert horology historian and accompanied by a text that elucidates the cultural and artistic contexts in which they were created. As a counterpoint to the timepieces, extensive reproductions of artistic masterpieces provide perspective regarding the technical advances of each period and demonstrate the evolution of aesthetic tastes over time.

François Chaille is passionate about art history, fashion, jewelry, and horology; he has published over a dozen works with Flammarion. A historian and expert on fine watchmaking, Dominique Fléchon is the author of many specialist works, including The Secrets of Vacheron Constantin and The Mastery of Time, both published by Flammarion. Franco Cologni is the author of numerous books, including The Cartier Tank Watch (Flammarion, 2017).

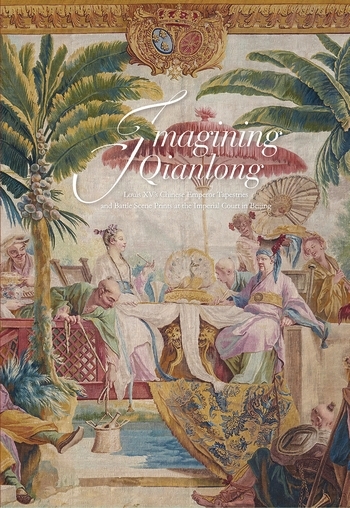

New Book | Imagining Qianlong

From Columbia University Press:

Florian Knothe, Pascal-François Bertrand, Kristel Smentek, and Nicholas Pearce, Imagining Qianlong: Louis XV’s Chinese Emperor Tapestries and Battle Scene Prints at the Imperial Court in Beijing (Hong Kong University Press, 2017), 84 pages, ISBN: 9789881902498, $25 / £20.

This publication accompanies an unprecedented exhibition (on view at Hong Kong University from 15 March until 28 May 2017) highlighting four of the magnificent chinoiserie tapestries of Chinese Emperor Qianlong, woven after designs by François Boucher at the famous Beauvais manufactory between 1758 and 1760. The large and well-preserved textiles form part of the royal French commission by King Louis XV, objects of which were presented to Qianlong in 1766.

This publication accompanies an unprecedented exhibition (on view at Hong Kong University from 15 March until 28 May 2017) highlighting four of the magnificent chinoiserie tapestries of Chinese Emperor Qianlong, woven after designs by François Boucher at the famous Beauvais manufactory between 1758 and 1760. The large and well-preserved textiles form part of the royal French commission by King Louis XV, objects of which were presented to Qianlong in 1766.

These celebrated tapestries are joined by another historic set of culturally related depictions in print—The Battles of the Emperor of China. The engravings were ordered by Qianlong, drawn by Jesuit painters at the Imperial Court in Beijing and then printed in Paris 1769–74. The ‘culture’ of these prints follows King Louis XIV’s influential images of the Histoire du Roi and presents Qianlong as both a war hero and as the undisputed leader of China in the mid-eighteenth century. These depictions date to the exact same time period, one that coincides with the high demand for chinoiserie in France—culminating in the world-famous designs by Boucher—and the Imperial Court of China’s interest in French design and culture. Despite their world-renowned fame, these groups of images previously have not been shown together.

Imagining Qianlong presents one of the rare topics to celebrate the court cultures in both France and China, at a time when the empires idolized each other, and cultural influences and exchanges were highly significant and supported by well-established and prosperous monarchs during an increasingly enlightened eighteenth century.

New Book | The Art of the Peales

Distributed by Yale UP:

Carol Eaton Soltis, The Art of the Peales in the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Adaptations and Innovations (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2017), 344 pages, ISBN: 978 0300229 363, $65.

Active from the late 18th through the early 20th century, the Peale family was America’s first artistic dynasty. This overview of the art of the Peales documents and interprets more than 160 works in a variety of media from the renowned collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. With discussions of both internationally famous masterworks such as Charles Willson Peale’s Staircase Group and lesser-known but equally engaging pictures including Rubens Peale’s Magpie Eating Cake, Carol Eaton Soltis traces the family’s history and reveals how the Peales’ energy, innovation, and entrepreneurship paved the way for generations of American artists.

Active from the late 18th through the early 20th century, the Peale family was America’s first artistic dynasty. This overview of the art of the Peales documents and interprets more than 160 works in a variety of media from the renowned collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. With discussions of both internationally famous masterworks such as Charles Willson Peale’s Staircase Group and lesser-known but equally engaging pictures including Rubens Peale’s Magpie Eating Cake, Carol Eaton Soltis traces the family’s history and reveals how the Peales’ energy, innovation, and entrepreneurship paved the way for generations of American artists.

Rigorously researched and generously illustrated, The Art of the Peales is an essential and wide-ranging study that considers the family’s substantial output and contextualizes their historical legacy. Examining the different ways that the Peales instructed, influenced, supported, and competed with one another, this book is full of new revelations on this extraordinary family that remained a transformative force in America’s cultural life for more than a century.

Carol Eaton Soltis is project associate curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Symposium | Continuing Curiosity: The Art of the Peales

From the Philadelphia Museum of Art:

Continuing Curiosity: The Art of the Peales

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 17 February 2018

On Saturday, 17 February, five Peale scholars share their ongoing research in the context of the Museum’s new publication, The Art of the Peales in the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Adaptations and Innovations. Registration required, $20 (Philadelphia Museum of Art members free). Included in the fee is general museum admission for Friday evening’s ‘Gallery Conversation’ (starting at 5:45pm), which includes an installation discussion with scholars, along with musical programming.

Morning Session | 10:30–12:30

• Welcome and introduction, Carol Soltis (Project Associate Curator, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

• ‘Pealed all Around’: The Making of Curious Revolutionaries at the American Philosophical Society, Amy Noel Ellison (Andrew W. Mellon Post-Doctoral Curatorial Fellow, American Philosophical Society)

• Under My Skin: Raphaelle Peale’s Venus Rising from the Sea-A Deception and the Hidden Mechanisms of Disease, Lauren Lessing (Mirken Director of Academic and Public Programs, Colby College Museum of Art)

Afternoon Session | 1:30–4:30

• Looking ahead with Charles Peale Polk, Linda Simmons (Curator Emerita, The Corcoran Gallery

• Replicating Nature: The Peales and Their Still Lifes, Lance Humphries (Executive Director, Mount Vernon Place Conservancy)

• Hanging Shakespeare: Charles Willson Peale and Benjamin West at PAFA in 1807, Wendy Bellion (Professor, Sewell C. Biggs Chair in American Art History, University of Delaware)

Exhibition | Georges Michel: The Sublime Landscape

Now on view at the Fondation Custodia:

The Sublime Landscape: Georges Michel

Monastère Royal de Brou, Bourg-en-Bresse, 6 October 2017 — 7 January 2018

Fondation Custodia / Collection Frits Lugt, Paris, 27 January — 29 April 2018

Curated by Ger Luijten and Magali Briat-Philippe

Admired by Vincent van Gogh, Georges Michel (1763–1843) is held to be the precursor of plein air painting. He was influenced by the painters of the Dutch Golden Age, earning the nickname of ‘the Ruisdael of Montmartre’. Yet today he is not widely known. The Fondation Custodia, in collaboration with the Monastère royal de Brou, is proposing to unveil the artist whose merits were first remarked by the dealer Paul Durand-Rueil in the nineteenth century. The first one-man exhibition for fifty years of the work of Georges Michel will be held from 27 January to 29 April 2018 at 121 rue de Lille, Paris. About fifty paintings and forty drawings—on loan mainly from French private and public collections—will be on show, and the exhibition will include some recent acquisitions by the Fondation Custodia.

Admired by Vincent van Gogh, Georges Michel (1763–1843) is held to be the precursor of plein air painting. He was influenced by the painters of the Dutch Golden Age, earning the nickname of ‘the Ruisdael of Montmartre’. Yet today he is not widely known. The Fondation Custodia, in collaboration with the Monastère royal de Brou, is proposing to unveil the artist whose merits were first remarked by the dealer Paul Durand-Rueil in the nineteenth century. The first one-man exhibition for fifty years of the work of Georges Michel will be held from 27 January to 29 April 2018 at 121 rue de Lille, Paris. About fifty paintings and forty drawings—on loan mainly from French private and public collections—will be on show, and the exhibition will include some recent acquisitions by the Fondation Custodia.

Georges Michel was born in Paris in 1763 and died there in 1843 after a remarkable career, whether in real terms or in a mythical post-mortem reconstruction of the life of this allegedly misunderstood artist. The main body of what we know about him comes from the biography written by Alfred Sensier in 1873, compiled from information recounted to him by the artist’s widow. Michel kept his distance from official art circles and only took part in the Salon between 1791—the date when the exhibition first opened its doors to artists who were not members of the former Académie royale—and 1814. His name was not mentioned thereafter until the sale of his work and the contents of his studio a year before his death.

The exhibition at the Fondation Custodia opens with youthful work by the artist, still betraying the influence of the eighteenth-century French landscape tradition as embodied in the art of Lazare Bruandet (1755-1804) or Jean-Louis Demaine (1752–1829), with whom Michel explored the Ile-de-France in search of subjects for sketching. He remained loyal to Paris and the surrounding countryside, claiming that ‘anyone unable to spend a lifetime painting within a range of four leagues is just a blundering fool searching for a mandrake—he will find only a void’. Saint-Denis, Montmartre or La Chapelle, the Buttes-Chaumont and the banks of the Seine, the countryside to the north of Paris offered a variety of hills and plains, dotted with quarries, mills and scattered dwellings.

Georges Michel’s style developed gradually away from the picturesque, anecdotic landscape that was in vogue between 1770 and 1830, achieving a notable originality. His paintings capture, with sincerity and a hint of the romanticism to come, the rural spots threatened with extinction as the villages around Paris began to be subsumed into the capital during the 1860s.

At a period when the painting of the Northern schools was enjoying a revival in France, Georges Michel, according to his widow, carried out some restoration work on Dutch paintings for the influential Paris dealer Jean-Baptiste Pierre Le Brun (1748–1813) and for the Muséum central des Arts (now the Musée du Louvre), at the behest of its director, Dominique Vivant Denon (1747–1825). Even though no trace of this activity can be found in the archives, Michel’s work is incontrovertibly influenced by the masters of the Dutch Golden Age. The exhibition at the Fondation Custodia—one of whose aims is to study the reception of Dutch art in France—takes this opportunity to compare Michel with the predecessors he so admired—and whose work he sometimes copied. From Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/1629–1682) he borrows compositions enlivened by vast, windswept skies, with sometimes a shaft of brilliant sunlight breaking through the clouds. The masterly chiaroscuro in his paintings, however, has its source in the work of Rembrandt (1606–1669). Philips Koninck (1619–1688), whose work in the eighteenth century was sometimes confused with that of Rembrandt, also evidently inspired Michel with his vast landscapes and limitless skies.

The Fondation Custodia, a home for art on paper in Paris, has recently acquired a large number of sheets by Georges Michel. The last section of the exhibition is devoted to these drawings. Michel’s prolific graphic work is characterised by its wide variety of techniques and subjects. The artist excelled in capturing vibrant views of Paris—in black chalk or, less frequently, pen and ink. The topographical nature of these drawings makes identification of the chosen locations simple: the Louvre, the Tuileries, the Jardin des Plantes, the Barrières de Ledoux.

Curators: Ger Luijten, director of the Fondation Custodia; and Magali Briat-Philippe, conservateur, responsable du service des patrimoines, Monastère royal de Brou.

More information, including a selection of images, is available here»

Magali Briat-Philippe and Ger Luijten, eds., Georges Michel: Le paysage sublime (Paris: Fondation Custodia, 2017), 208 pages, ISBN 978 9078655 268, 29€.

Exhibition | The Object of My Affection

Now on at the The Fitzwilliam:

The Object of My Affection: Stories of Love from the Fitzwilliam Collection

The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 30 January — 28 May 2018

Love is very much in the air in this exhibition, which contains objects alive with the range of emotions that it commands: from admiration and affection, joy and passion, longing and despair, to insults, indifference, grief and remembrance. The exhibition showcases the Fitzwilliam Museum’s collection of valentines, which date from the 18th century to the 20th and include a wide variety of sentimental and decorative types as well as comic examples. Alongside the valentines will be an assortment of other objects relating to the theme of love, including posy rings, love tokens, and works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) and James Gillray (1756–1815).

Rebecca Virag, Valentines: Highlights from the Collection at The Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge: The Fitzwilliam, 2018), 120 pages, £10.

It is probably a little known fact that the Fitzwilliam Museum has a large collection of around 1,600 valentines, which range in date from the early eighteenth century to the 1920s. The vast majority were left to the Museum in 1928 by mathematician and Fellow of Trinity College, J.W.L. Glaisher. Two more Cambridge alumni, the Rev. Herbert Bull (Trinity) and Sir Stephen Gaselee (King’s) also gave their much smaller collections of valentines to the Museum in 1917 and 1942. The Bull valentines are particularly fascinating as they are rare survivals of mid-eighteenth century silhouette cut-paper work and are unlike anything collected by either Glaisher or Gaselee. The Glaisher collection alone is one of the largest amassed by a single collector currently in a UK public collection.

It is probably a little known fact that the Fitzwilliam Museum has a large collection of around 1,600 valentines, which range in date from the early eighteenth century to the 1920s. The vast majority were left to the Museum in 1928 by mathematician and Fellow of Trinity College, J.W.L. Glaisher. Two more Cambridge alumni, the Rev. Herbert Bull (Trinity) and Sir Stephen Gaselee (King’s) also gave their much smaller collections of valentines to the Museum in 1917 and 1942. The Bull valentines are particularly fascinating as they are rare survivals of mid-eighteenth century silhouette cut-paper work and are unlike anything collected by either Glaisher or Gaselee. The Glaisher collection alone is one of the largest amassed by a single collector currently in a UK public collection.

The Glaisher valentines have not been seen in public since 1995, some twenty-three years ago, and since then the entire valentine collection has been catalogued, researched, photographed, and re-housed. This selection of highlights has been published to coincide with a new display of some of these extraordinary objects as part of the exhibition The Object of my Affection: Stories of Love from the Fitzwilliam Collection.

The Huntington Acquires Major Collection of Valentines

Press release (12 February 2018) from The Huntington:

Fraktur labyrinth, Pennsylvania-German folk art, inscribed 1824; drawn and hand-colored on paper. 15½” x 15½” framed; designed as an endless knot with classic Pennsylvania-German motifs including hearts, tulips, and compass roses, and offered as a token of affection (The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens).

A spectacular trove of thousands of valentines and related material—some dating as far back as the late 17th century—has been given to The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, the institution announced today. Considered the best private collection of its kind in the world, the Nancy and Henry Rosin Collection of Valentine, Friendship, and Devotional Ephemera contains approximately 12,300 greeting cards, sentimental notes, folk art drawings, and other tokens of affection that trace the evolution of romantic and religious keepsakes made in Europe and North America from 1684 to 1970. The Rosins had given the collection to their son, Bob, who together with his wife, Belle, donated it to The Huntington for safekeeping. “This collection was carefully created by my parents,” he said. “I can’t think of a better place for it to be, given its historical and educational value.”

The Rosin Collection brims with well-preserved paper (and in some cases, vellum or mixed media) materials that range from lacy 18th-century devotional cards, hand-cut by French and German nuns, to elegant Biedermeier-era (1815–1848) greeting cards complete with hand-painted love scenes, gilded embossing, mother-of-pearl ornaments, and silk chiffon. The collection includes cameo-embossed lace paper valentines from England, elaborate three-dimensional and mechanical Victorian paper confections, as well as handmade works of American folk art demonstrating traditional paper-cut techniques (scherenschnitte) and colorful Germanic Fraktur illustrations. Some of the most historically significant items include heartrending Civil War soldiers’ valentines with personal notes detailing the hardship of war and longing for home. The Rosin Collection also contains bitingly satiric ‘vinegar’ valentines, dance cards, memory albums, and watch papers (sentimental notes inserted into pocket watches), among other items relating to the history of love and devotion.

“We are profoundly grateful to Bob and Belle Rosin for this invaluable, and truly beautiful collection that was so carefully developed,” said Sandra L. Brooke, Avery Director of the Library at The Huntington. “It will dramatically enhance our holdings in several areas to which we are committed—especially 19th-century social history and visual culture, and of course, our renowned U.S. Civil War material.”

Nancy Rosin is president of the National Valentine Collectors Association, president emerita of the Ephemera Society of America, and a member of the American Antiquarian Society and The Grolier Club. She says collecting valentines has been her “passionate obsession” for 40 years. “My quest to acquire sentimental expressions of love, especially those celebrating Valentine’s Day—a significant social event that was enjoyed by all strata of society—grew into a desire to share them with the public,” said Rosin. “Bob grew up watching us build this collection piece by piece. I’d long hoped the collection would end up where it would have the most research value and the highest standard of preservation, so it is deeply gratifying to know Bob and Belle have given these works to The Huntington.”

The Huntington’s collection of historical prints and ephemera was begun by its founder, Henry E. Huntington, about 100 years ago, and has since grown to contain hundreds of thousands of items that support public exhibitions and scholars’ research, especially in the areas of British and American cultural history. The Rosin Collection significantly increases the institution’s distinction of being one of the leading archives for ephemera studies.

“This is a collection I’ve been familiar with and admired for many years,” said David Mihaly, Jay T. Last Curator of Graphic Arts and Social History at The Huntington. “It is without a doubt the best in private hands in terms of quality and range within its focus—to say nothing of the sheer wonder and delight the items provide. Pull a string and an ingenious cobweb device lifts to reveal a mouse in a trap; unfold a die-cut valentine and watch a majestic carriage spring to life in 3-D; read a witty poem and realize it’s a hilarious jab at a Victorian-era politician; look closely at a tiny, centuries-old card and see it was delicately perforated with hundreds of tiny pinpricks, and hand painted so expertly. We certainly will enjoy researching and processing this collection—and hope to plan an exhibition in coming years.”

The institution expects to start preserving and cataloguing the Rosin Collection this year, with research access soon to follow.

Exhibition | Pockets to Purses

Next month at FIT:

Pockets to Purses: Fashion + Function

The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, 6–31 March 2018

Organized by Graduate Students in FIT’s Fashion and Textile Studies Program

The Fashion Institute of Technology’s School of Graduate Studies and The Museum at FIT present Pockets to Purses: Fashion + Function. Organized by graduate students in the Fashion and Textile Studies program, the exhibition explores pockets and purses as both fashionable and functional objects by tracing both their history and evolution to accommodate the demands of modern life. Displaying objects from the collection of The Museum at FIT, the exhibition analyzes the interplay between pockets and purses in both men’s and women’s wardrobes from the 18th century to the present. In addition to garments and accessories, the exhibition features photographs, advertisements, and film clips that demonstrate how pockets and purses have been utilized throughout history and the ways that lifestyle changes have affected their design and use.

Reticule of a Man’s Waistcoat, embroidered silk, ca. 1800, France (NY: The Museum at FIT, gift of Thomas Oechsler. 93.132.2).

Pockets to Purses: Fashion + Function begins with 18th-century examples of men’s and women’s pockets. Men’s pockets were built into jackets or waistcoats so that men could carry a variety of objects, including books. Problematically, the lines of a man’s tailored ensemble were often disrupted by bulky items. Alternatively, women’s pockets began as separate accessories that were tied to the body and worn underneath a skirt. These pockets were completely hidden, allowing a woman to carry items while maintaining privacy.

Changing fashions and evolving roles in society led to women carrying their possessions in handheld bags. A reticule—a small handbag typically made with a drawstring closure—displayed in the exhibition illustrates the evolution of pockets into handheld purses. The shape, ornamentation, and pocket flap of this example from circa 1800 indicate that it was fabricated from an 18th-century man’s waistcoat, an example of which can be seen in the rendering on a fashion plate dating from 1778 to 1787. A blue bodice from circa 1878 that features a small watch pocket on the left hip reveals a fashionable approach to practical design. The pocket has embroidered decoration, but the easily accessible location and convenient shape of the pocket are function driven.

A needlepoint bag dating from 1920–30 contains three small cases that demonstrate the prevalence for ensemble dressing that arose during the 1920s. The coordinating containers for cigarettes and face powder testify to a growing acceptance of women smoking and wearing makeup in public. The tension between fashion and function continued into the 20th century. The exhibition includes an ad for Elsa Schiaparelli’s ‘Cash and Carry’ suits, which featured large pockets on the hips for carrying supplies, demonstrating the desire for functionality that prevailed at the outbreak of World War II. After the war, designers deemphasized functionality and began to feature pockets primarily as design elements. A Molyneux dress from 1948 has eight strategically placed pockets on the hips that make the waist appear smaller, a silhouette that dominated postwar fashion.

American designers such as Claire McCardell and Bonnie Cashin incorporated pockets that were as playful as they were practical. A bright green raincoat by Cashin circa 1965 features a pocket designed to look like a shoulder bag—making her raincoat a visual fusion of fashion and function. Made from leather, canvas, and the twist-lock closures that were typical of Cashin’s work, the coat’s large, practical pocket allowed the wearer to go hands-free while keeping her possessions close.

Novelty bags demonstrate the whimsy of fashion, though they also convey wealth and status. A 1950s Lederer purse shaped like a clock has a built-in lipstick compartment and utilizes traditional elegant materials in a novel design. Additionally, Judith Leiber’s 1994 Swarovski crystal-encrusted minaudière in the shape of a tomato was designed to be a display of glamour and imagination. Both examples present the handbag as an objet d’art and show how designers sometimes perform more as artists, focusing on form rather than functionality.

Other iterations of the status bag, specifically those of the late 20th century, are also on display. An Hermès “Kelly” bag from 2000 demonstrates the longevity of the bag’s design, which set standards for the luxury market when it was introduced as a saddle bag in 1892. Alternatively, a Louis Vuitton purse from 2003 shows a trendier kind of status bag. Its colorful take on the traditional Vuitton ‘Speedy’ bag played into passing fashion trends during the early 2000s.

Various menswear items are also included, such as a 1990 sport coat by Jean Paul Gaultier. With layers of cargo pockets, velcro flaps, and heavy-duty zippers, this jacket is a take on the functional pockets in conventional men’s sportswear. Similarly, a bowler hat designed by Rod Keenan in 2006 subverts the traditional bowler by including, at the crown, a pocket made to hold a condom.

The final section of the exhibition focuses on pockets that allude to historical embellishments. Included are a Bill Blass knit dress from fall 1986 and a man’s Versace suit from 1992. Shown alongside a reproduction of an 18th-century man’s embroidered coat, these objects are reminders of the pocket’s fashionable use throughout history.

Exhibition | Pink

This fall at FIT:

Pink: The History of a Punk, Pretty, Powerful Color

The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, 7 September 2018 — 5 January 2019

Curated by Valerie Steele

Pink is popularly associated with little girls, ballerinas, Barbie dolls, and all things feminine. Yet the symbolism and significance of pink have varied greatly across time and space. The stereotype of pink-for-girls versus blue-for-boys may be ubiquitous today, but it only gained traction in the mid-twentieth century. In the eighteenth century, when Madame de Pompadour helped make pink fashionable at the French court, it was perfectly appropriate for a man to wear a pink suit, just as a woman might wear a pink dress. In cultures such as India, men never stopped wearing pink.

Yet anyone studying pink comes up against “the color’s inherent ambivalence.” One of “the most divisive of colors,” pink provokes strong feelings of both “attraction and repulsion.” “Please sisters, back away from the pink,” wrote one journalist, responding to the pink pussy hats worn at the Women’s March. Some people think pink is pretty, sweet, and romantic, while others associate it with childish frivolity or flamboyant vulgarity. In recent years, however, pink increasingly has been interpreted as cool, androgynous, and political. “Why would anyone pick blue over pink?” mused the rapper Kanye West. “Pink is obviously a better color.” In the words of i-D magazine, pink is “punk, pretty, and powerful.”

Curated by Dr. Valerie Steele, director of The Museum at FIT, Pink: The History of a Punk, Pretty, Powerful Color will explore the changing significance of the color pink over the past three centuries.

New Book | Versailles et l’Europe

All essays are available for download as PDF files from ArtHistoricum.net:

Thomas Gaehtgens, Markus Castor, Frédéric Bussmann, and Christophe Henry, eds., Versailles et l’Europe: L’appartement monarchique et princier, architecture, décor, cérémonial (Paris: Centre allemand d’histoire de l’art 2018), 896 pages, ISBN: 9782955931509.

Les 31 contributions de cet ouvrage examinent en premier lieu la signification et la fonction des appartements royaux de Louis XIV en France, puis leur réception dans les cours du Saint Empire romain germanique, avant de s’intéresser aux résidences des Pays-Bas, de l’Angleterre, de la Suède, de la Pologne et de l’Espagne au cours des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles.

Les 31 contributions de cet ouvrage examinent en premier lieu la signification et la fonction des appartements royaux de Louis XIV en France, puis leur réception dans les cours du Saint Empire romain germanique, avant de s’intéresser aux résidences des Pays-Bas, de l’Angleterre, de la Suède, de la Pologne et de l’Espagne au cours des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles.

Der vorliegende Band untersucht den Einfluss eines der brillantesten Repräsentationsleistungen der Frühen Neuzeit auf die europäischen Höfe des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts. Das Versailler Schloss, ein „Showroom“, der die französischen Luxusgüter über die Grenzen hinaus bekannt und zum begehrten Gut machte, zog die Blicke aller Regenten der Zeit auf sich. Doch wenngleich von Künstlern und Kunsthandwerkern, die sich an den europäischen Höfen niederließen, zahlreiche Formen und Ideen übernommen wurden, darf die Beharrlichkeit der lokalen Traditionen dennoch nicht unterschätzt werden.

Beginnend mit einer Analyse des Versailler Appartements nach Form und Funktion wird das in Frankreich entwickelte Modell in seiner Bedeutung für die Konzepte des Appartements der europäischen Höfe betrachtet. Die Beiträge analysieren das Zusammenspiel von Architektur, Dekor und Zeremoniell und die besondere Bedeutung des Appartements für die höfische Repräsentation. Die räumliche Disposition tritt als komplexes Verweissystem hervor, das die Inszenierung der Macht und die Zugänglichkeit des Regenten bestimmte. Die Logik der Ausstattungssysteme erschließt sich nur in interdisziplinärer Betrachtung, die auch die sozialen und politisch—historischen Bedingungen berücksichtigt. Bereits vorhandene Traditionen der europäischen Häuser werden in diesem Prozess zwischen Übernahmen und Transformationen neu konfiguriert.

Der erste Teil widmet sich dem in Frankreich entwickelten Modell des Appartements und versucht die komplexe Entwicklung in Versailles bis 1701 nachzuvollziehen, in der die Chambre de Parade zum Herzstück des Schlosses wurde. Im zweiten Teil beleuchten die Fallstudien zu Residenzen der deutschsprachigen Länder den komplexen Austausch und die Vielfalt der heterogenen Lösungen. Mit Beiträgen zu einigen wesentlichen europäischen Höfen in England, Holland, Schweden, Polen, Spanien und Italien schließt die Studie ab.

Thomas W. Gaehtgens (Director, Getty Research Institute, LA); Markus A. Castor (Directeur de Recherche, DFK-Paris); Freddric Bussmann (Kurator, Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig); Christophe Henry (Professeur Grandes Ecoles, Histoire et theorie des arts).

C O N T E N T S

Thomas Kirchner, Préface

Thomas Gaehtgens, Markus Castor, Frédéric Bussmann, Appartement, décor et cérémonial: une introduction

Versailles et la France

• Raphaël Masson, Thierry Sarmant, COMITAS ET MAGNIFICENTIA. Essai sur l’appartement royal en France

• Jean-Pierre Samoyault, L’appartement du roi à Fontainebleau sous Louis XIV (1643–1715)

• Stéphane Castelluccio, L’appartement du roi à Versailles, 1701 : le pouvoir en représentation

• Max Tillmann, « Une étiquette prétentieuse » La cour princière de l’électeur Max-Emmanuel de Bavière au château de Compiègne (1708–1715)

• Jörg Garms, Les appartements du duc Léopold à Lunéville

Les cours princières du Saint-Empire entre Habsbourg et Bourbon

• Katharina Krause, Des exemples à suivre absolument ? Distribution française et commodité allemande dans le traité et la pratique architecturale au tournant du xviiie siècle

• Cordula Bischoff, Le Frauenzimmer-Ceremoniel (cérémonial des femmes) et ses conséquences sur la distribution des appartements princiers des dames vers 1700

• Rainer Valenta, L’appartement impérial à l’époque de Charles VI. Proposition de reconstitution

• Ulrike Seeger, L’appartement électoral entre Vienne et Versailles. L’appartement de parade de la résidence princière de Rastatt

• Annegret Kotzurek, Les appartements ducaux du corps de logis baroque du château de Ludwigsbourg

• Kathrin Ellwardt, Les appartements du château de Mannheim

• Eva-Bettina Krems, « Le sujet est de ceux qui […] s’accompagnent du plus grand nombre de pointillés. » – De la diversité des espaces d’audience dans les châteaux français et allemands autour de 1700

• Henriette Graf, La fonction des appartements de l’électeur Charles-Albert de Bavière dans le cérémonial de cour vers 1740

• Virginie Spenlé, Galeries de peintures et appartements princiers dans le Saint-Empire romain germanique

• Marc Jumpers, L’appartement d’apparat de la résidence de Bonn : une tentative de reconstitution

• Martin Miersch, Le rôle des diplomates français dans la formation du « bon goût » chez le prince électeur de Cologne Clément-Auguste

• Frédéric Bussmann, Le château de Nordkirchen, le « Versailles de Westphalie » ? Architecture, distribution et décor des appartements de la résidence du prince évêque de Münster et de la famille Plettenberg

• Verena Friedrich, La décoration française à la résidence de Wurtzbourg. Les projets du premier appartement de l’évêque de Wurtzbourg

• Claudia Schnitzer, « …afin d’en laisser à la postérité un souvenir ineffaçable » Les pièces de parade du château de Dresde dans la relation de la fête organisée à l’occasion du mariage de 1719

• Katja Heitmann, Distribution et ornementation. Le château de Heidecksburg à Rudolstadt et l’influence de l’architecture française sur les châteaux princiers allemands

• Martin Pozsgai, L’appartement de parade dans les châteaux des princes protestants du Saint-Empire romain germanique

• Guido Hinterkeuser, Les pièces d’habitation et les salles d’apparat de Sophie-Charlotte et Frédéric Ier au château de Charlottenburg : finalité, aménagement et usage

• Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Frédéric Ier, Frédéric -Guillaume Ier et Frédéric II. Trois conceptions de la représentation et de l’habitat princier à la cour de Prusse

• Peter O. Krückmann, Le Vieux Château de l’Ermitage à Bayreuth. L’iconographie du pouvoir au temps de l’absolutisme et des Lumières

Les autres grandes cours européennes, un tour d’horizon

• Johan de Haan, L’appartement princier au palais du Stadhouder à Leeuwarden 1650–1710

• Konrad Ottenheym, Les appartements princiers des résidences du prince d’Orange dans la Hollande du xviie siècle

• Michael Schaich, La chambre de parade sous la monarchie anglaise autour de 1700

• Linda Hinners, Martin Olin, Les appartements royaux du château de Stockholm

• Anna Olenska, L’Union de Pologne-Lituanie a-t-elle eu son « Versailles » ? Du Wilanów de Jean III Sobieski au Bialystok du prétendant au titre de Jean IV Branicki

• Elisabeth Wünsche- Werdehausen, Entre Bourbon et Habsbourg ? Les grands appartements du palais royal de Turin

• Markus A. Castor, Anne Kurr, Philippe V de Bourbon à Madrid -Architecture, décor et cérémonial entre changement programmatique et tradition

Plans des châteaux

Abrévations

Bibliographie

Glossaire franco-allemand

Index des noms propres

Index topographique

Crédits photographiques

leave a comment