Exhibition: The Eighteenth Century Back in Fashion

From the Palace of Versailles:

Le XVIIIe au goût du jour / A Taste of the Eighteenth Century

Grand Trianon, Château de Versailles, 8 July — 9 October 2011

Curated by Olivier Saillard

The Palace of Versailles and the Musée Galliera present an exhibition in the apartments of the Grand Trianon dedicated to the influence of the 18th century on modern fashion. Between haute couture and ready-to-wear, fifty models by great designers of the 20th century dialogue with costumes and accessories from the 18th century and show how this century is quoted with constant interest. These pieces come from the archives of maisons de couture and from the Galliera’s collections.

The Palace of Versailles and the Musée Galliera present an exhibition in the apartments of the Grand Trianon dedicated to the influence of the 18th century on modern fashion. Between haute couture and ready-to-wear, fifty models by great designers of the 20th century dialogue with costumes and accessories from the 18th century and show how this century is quoted with constant interest. These pieces come from the archives of maisons de couture and from the Galliera’s collections.

Influencing all the European courts, French culture of the 18th century was embodied by Madame de Pompadour, Madame Du Barry and even more so Marie-Antoinette – paragons of frivolity that has always fascinated the cinema, literature and the fashion world. With its huge powdered hairstyles, whalebone stays and hoop petticoats, flounces, frills and furbelows, garden swings and whispered confidences, the 18th century brought artifice to its paroxysm…

A fantasized style which gives free rein to interpretation: the Boué Sisters in the twenties revive panniers and lace in their robes de style, Christian Dior and Pierre Balmain offer evening gowns embroidered with typically 18th-century decorative patterns, Vivienne Westwood brings back brazen courtesans, fashionable Belles are corsetted by Azzedine Alaïa, Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel invites Watteau with his robes à la française, the Maison Christian Dior adorns duchesses with delicate attires, Christian Lacroix drapes his queens with brocades lavishly gleaming with gemstones and Olivier Theyskens for Rochas summons up the ghost of Marie-Antoinette in a Hollywood film.

A fantasized style which gives free rein to interpretation: the Boué Sisters in the twenties revive panniers and lace in their robes de style, Christian Dior and Pierre Balmain offer evening gowns embroidered with typically 18th-century decorative patterns, Vivienne Westwood brings back brazen courtesans, fashionable Belles are corsetted by Azzedine Alaïa, Karl Lagerfeld for Chanel invites Watteau with his robes à la française, the Maison Christian Dior adorns duchesses with delicate attires, Christian Lacroix drapes his queens with brocades lavishly gleaming with gemstones and Olivier Theyskens for Rochas summons up the ghost of Marie-Antoinette in a Hollywood film.

While the elegant simplicity in black and white is played by Yves Saint Laurent, Martin Margiela transforms men’s garments into women’s, Nicolas Ghesquière for Balenciaga enhances women in little marquis dressed with lace and Alexander McQueen for Givenchy clothes his marquises in vests embroidered with gold thread. With Yohji Yamamoto, court dresses are destructured and so does Rei Kawakubo with riding coats. While Thierry Mugler hides oversized hoops under the dresses, Jean Paul Gaultier puts them upside down.

Couturiers and fashion designers invite you to discover this 18th century back in fashion, in the Grand Trianon.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Suzy Menkes’s review for The New York Times (11 July 2011), is available here»

Exhibition: Paper Dresses of Isabelle de Borchgrave

From the Legion of Honor Museum:

Pulp Fashion: The Art of Isabelle de Borchgrave

Legion of Honor, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 5 February — 5 June 2011

Curated by Jill D’Alessandro

Belgian artist Isabelle de Borchgrave is a painter by training, but textile and costume are her muses. Working in collaboration with leading costume historians and young fashion designers, de Borchgrave crafts a world of splendor from the simplest rag paper. Painting and manipulating the paper, she forms trompe l’oeil masterpieces of elaborate dresses inspired by rich depictions in early European painting or by iconic costumes in museum collections around the world. The Legion of Honor is the first American museum to dedicate an entire exhibition to the work of Isabelle de Borchgrave, although her creations have been widely displayed in Europe.

Belgian artist Isabelle de Borchgrave is a painter by training, but textile and costume are her muses. Working in collaboration with leading costume historians and young fashion designers, de Borchgrave crafts a world of splendor from the simplest rag paper. Painting and manipulating the paper, she forms trompe l’oeil masterpieces of elaborate dresses inspired by rich depictions in early European painting or by iconic costumes in museum collections around the world. The Legion of Honor is the first American museum to dedicate an entire exhibition to the work of Isabelle de Borchgrave, although her creations have been widely displayed in Europe.

Pulp Fashion draws on several themes and presents quintessential examples in the history of costume—from Renaissance finery of the Medici family and gowns worn by Elizabeth I and Marie-Antoinette to the creations of the grand couturiers Frederick Worth, Paul Poiret, Christian Dior, and Coco Chanel. Special attention is given to the creations and studio of Mariano Fortuny, the eccentric early-20th-century artist who is both a major source of inspiration to de Borchgrave and a kindred spirit.

Catalogue: Jill D’Alessandro, Pulp Fashion: The Art of Isabelle de Borchgrave (Prestel, 2011), 104 pages, ISBN: 9783791351056, $29.95.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the artist’s website (worth visiting for lots more amazing images). . .

Isabelle de Borchgrave, "Madame de Pompadour paper dress," inspired by a 1755 painting by Maurice Quentin de la Tour, 85 cm x 65 cm x 165 cm, 2001 (Photo: René Stoeltie).

. . . . Following a visit to the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 1994, Isabelle dreamed up paper costumes. While keeping her brushes in hand and her paintings in mind, she worked on four big collections, all in paper and trompe l’œil, each of which set the scene for a very different world. “Papiers à la Mode” (Paper in Fashion), the first, takes a fresh look at 300 years of fashion history from Elizabeth I to Coco Chanel. “Mariano Fortuny” immerses us in the world of 19th century Venice. Plissés, veils and elegance are the watchwords of that history. “I Medici” leads us through the streets of Florence, were we come across famous figures in their ceremonial dress. Figures who made the Renaissance a luminous period. Gold-braiding, pearls, silk, velvet … here, trompe l’œil achieves a level of rediscovered sumptuousness. As for the “Ballets Russes”, they pay tribute to Serge de Diaghilev. Pablo Picasso, Léon Bakst, Henri Matisse, … all designed costumes for this ballet company, which set the world of the 20th century alight. These dancing paper and wire figures play a very colourful and contemporaneous kind of music for us.

It’s true that, today, Isabelle de Borchgrave has become a name that is readily associated with fashion and paper. But her name is also closely linked to the world of design. By working together with Caspari, the potteries of Gien, Target, and Villeroy and Boch, Isabelle has turned her imagination into an art that’s accessible to anyone who wants to bring festivity into their home. Painted fabrics and paper, dinner services, curtains, sheets, decor with a personal touch for parties and weddings,… All this tells of the world in which she has always loved to move.

But in a 40-year career, she has never put to one side the thing that has always guided her in her life: painting. She still exhibits her paintings and her large folded paper works all over the world. With an imagination increasingly stimulated by her knowledge and interpretation of art, Isabelle, a follower of the Nabis movement, has a fresh perspective of a world that flies around her like a dream.

Ann Mah: Walking (and Drinking) in Jefferson’s Footsteps

From Ann Mah, “Following Jefferson through the Vineyards,” The New York Times 3 June 2010:

In Pommard, a plaque commemorates Jefferson’s visit to the region (Ed Alcock for The New York Times)

When Thomas Jefferson embarked on his grand tour of France in 1787, he claimed the journey was for his health. A broken wrist sent him on a circuitous route, 1,200 miles south from Paris to take the mineral waters at Aix-en-Provence, and on the way he planned to fulfill his professional obligations as America’s top envoy to France, researching French architecture, agriculture and engineering projects.

But when he chose to begin his three-month journey in the vine-covered slopes of Burgundy, Jefferson’s daughter, Martha, became suspicious. “I am inclined to think that your voyage is rather for your pleasure than for your health,” she teased him in a letter.

In fact, Jefferson’s five-day visit to the Côte d’Or — a region famous even in the 18th century for its extraordinary terroir — was not accidental. After spending more than two years in Paris establishing diplomatic relations with the court of Louis XVI, Jefferson, a lifelong oenophile, had tasted his share of remarkable vintages. Now he was keen to discover the vineyards and cellars of Burgundy, and to study firsthand a winemaking tradition that stretched back to the 11th century. “I rambled thro’ their most celebrated vineyards, going into the houses of the laborers, cellars of the vignerons, and mixing and conversing with them as much as I could,” Jefferson wrote about the winemakers in a letter posted during his trip.

Although almost 225 years, a revolution, a vine-ravaging epidemic and several wars separate us from Jefferson’s wine tour, I discovered on a recent trip that it is still possible to explore the celebrated swath of vine-covered hills as the self-described “foreign gentleman” once did . . .

The full article is available here»

Tome Tweet Tome?

From the Editor

An admission: I’ve never tweeted, nor regularly followed anyone who does. I’m hardly opposed to Twitter on principle, and as someone who stresses to my students the importance of tightly-edited writing, I think there could be immense value in forcing individuals to communicate with just 140 characters at a time. Still, I’ve yet to be persuaded it’s for me. Nonetheless, the following pieces at least have me thinking about it (given that the text up to this point weighs in at 428 characters, I clearly have a long way to go).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Jon Lackman, the editor of The Art History Newsletter, kindly sent me a link to this story, “Twitter Updates, the 18th-Century Edition,” posted at The Wall Street Journal by Jennifer Valentino-DeVries:

There aren’t too many things more 21st century than Twitter. But it turns out that the way people share information on Twitter bears some similarities to the way they shared it more than 200 years before the service was created in 2006, according to Cornell professor Lee Humphreys, who has been comparing messages from Twitter and those from diaries in the 18th and 19th centuries. A quick look at a few of the entries from several diaries shows that Twitter’s famous 140-character limit wouldn’t have been a problem for these writers:

April 27, 1770: Made Mead. At the assembly.

May 14, 1770: Mrs. Mascarene here and Mrs. Cownsheild. Taken very ill. The Doctor bled me. Took an anodyne.

Sept. 7, 1792: Fidelia Mirick here a visiting to-day.

Jan. 26, 1873: Cold disagreeable day. Felt very badly all day long and lay on the sofa all day. Nothing took place worth noting.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Writing for The New York Times (30 April 2010), Randall Stross notes that today’s millions of tweets may in fact be the stuff of primary source material for future historians.

. . . Not a few are pure drivel. But, taken together, they are likely to be of considerable value to future historians. They contain more observations, recorded at the same times by more people, than ever preserved in any medium before.

“Twitter is tens of millions of active users. There is no archive with tens of millions of diaries,” said Daniel J. Cohen, an associate professor of history at George Mason University and co-author of a 2006 book, “Digital History.” What’s more, he said, “Twitter is of the moment; it’s where people are the most honest.”

Last month, Twitter announced that it would donate its archive of public messages to the Library of Congress, and supply it with continuous updates. . . .

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

And if anyone’s looking for examples of art historical tweets, the following list of “100 Excellent Twitter Feeds for Art Scholars,” might be useful.

All the same, at this point, I’ve no immediate plans to tweet for Enfilade. Yet, if any HECAA members feel strongly that we’re missing out on something, I certainly am open to offers from interested volunteers. . . Or just your own sense of Twitter’s scholarly or institutional value. -C.H.

Bon Mardi Gras

From the website of the Réunion des musées nationaux (RMN):

Josephine’s Wine Cellar at Malmaison during the Empire

Châteaux de Malmaison and de Bois-Préau Museum, 18 November 2009 — 8 March 2010

Carafe with Josephine’s monogram, First Empire (1804-1814), crystal, Musée National des Châteaux de Malmaison et Bois-Préau © Rmn / André Martin

The idea for this exhibition came from the inventory drawn up after the death of the Empress Josephine which listed the contents of the cellar at Malmaison – over thirteen thousand bottles. The list of wines served to guests in the house is striking for the number of crus mentioned and the variety of the regions they came from. The best crus from Bordeaux and Burgundy stand alongside Mediterranean wine, in the sweet, syrupy taste of the eighteenth century, the most famous names in Champagne, wines from Languedoc-Roussillon, Côtes du Rhône and the Rhineland. Rum and liqueurs from the West Indies are a reminder of the Empress’ origins.

The exhibition attempts to show the evolution of wine production and marketing during the Empire. It was boosted by progress in the glassmaking industry, which was particularly noticeable in the shape of the bottles. Iconographic documents and account books kept by Josephine’s suppliers reveal the variety and quantity of the empress’ orders.

Elegant ice buckets, glass coolers, crystal and metal punch bowls illustrate the refinement and prestige of the tableware at Malmaison and stand alongside the most brilliant pieces of glassware, some bearing the monograms the sovereigns from Josephine to Louis-Philippe. The latter demonstrate the technical progress made in French glassmaking, which facilitated the search for new forms, and bear witness to the evolution of table manners in the years after the revolution. Objects made after the Consulate and the Empire complement this rich overview and show the changes in the production of glassmaking, bottling and labelling in the first half of the nineteenth century up until the beginning of the Second Empire.

With the classification of the grands vins of Bordeaux in 1855 and developments in transportation, this was a period of deep change. A final section is dedicated to the representation of wine in the Napoleonic legend.

The exhibition brings together more than two hundred objets d’art and iconographic documents not only from the Musée de Malmaison but from the collections of the museums of the Château de Fontainebleau, the Château de Compiègne, the Château d’Eu (Musée Louis-Philippe), the Musée Carnavalet, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, the Musée National de Céramique de Sèvres, the Archives Nationales, the Fondation Napoléon, the musée Napoléon Thurgovie, château et parc d’Arenenberg, (canton of Thurgovia, Switzerland) and the Museo Napoleonico, Rome. Other items are on loan from industrial or commercial firms such as Moët et Chandon, or from private collections. Taking an artistic and historical angle, the exhibition shows that Josephine’s cellar is a precious testimony to the gracious entertaining which long made the charm and reputation of Malmaison. (more…)

Lighting the Lights

At the start of Hanukkah, some eighteenth-century highlights from the recent sale at Sotheby’s in New York of Important Judaica (Sale 8606, 24 November 2009), as drawn from Sotheby’s website:

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Lot 86: Property of a Descendant of Selig Meier Goldschmidt – An Important German Parcel-Gilt Silver Hanukah Lamp, probably from Augsburg, ca. 1750

Estimate: 200,000—300,000 USD; Hammer Price with Buyer’s Premium: 542,500 USD

Height 13in. by length 12 3/8 in.

Height 13in. by length 12 3/8 in.

Raised at the front on four lion couchant feet, supporting scroll-based columns draped with floral pendants, each with two putti supporters and topped by figures of Judith, with sword and head, and David, with sling and spear, the backplate centered by a baroque cartouche surrounded by diaper and flanked by cornucopiae spilling flowers and topped by a flower-filled urn, all surmounted by two draped putti (formerly holding a shamas, now lacking), the leaf-form fonts above a shaped apron with fruit pendants, the lion rampant holding the Tablets applied probably later to backplate

Marked with large and small Austrian control mark for Brünn (now Brno, Czech Republic) 1806-07, and twice with Dutch control mark for foreign work (used 1813-1893)

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

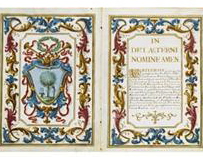

Lot 160: Medical Diploma of Israel Barukh Olmo, Manuscript on Vellum from Padua, 1755

Estimate: 25,000—35,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer’s Premium: 31,250 USD

4 leaves (9 ¼ x 6 ¾ in.; 236 x 170 mm); Written in brown and gold ink on vellum, f. 4 blank. Decorated. Contemporary mottled calf, gilt tooled border.

4 leaves (9 ¼ x 6 ¾ in.; 236 x 170 mm); Written in brown and gold ink on vellum, f. 4 blank. Decorated. Contemporary mottled calf, gilt tooled border.

From the 16th through the 18th centuries, the prestigious medical school of the University of Padua was one of the only European institutions of higher education that allowed Jews to attend. According to university records, only 230 Jews graduated in the more than two centuries between 1517-1721. It was customary, upon graduation, to commission diplomas in the form of small richly decorated booklets and the format and style of these diplomas was unique to universities in Northern Italy. The text of the standard diploma, however, included references to Christianity which were unsuitable for the Jewish graduates. As may be seen in the present lot, the university, demonstrating considerable tolerance, allowed for the alteration of the customary Christian formulae. Whereas the standard diplomas from Padua began with the words “In Christi Nomine aeterni” and recorded the date as “Anno a Christi nativitate,” diplomas created for Jews substituted these phrases with “In Nomine Dei aeterni” and “currente anno.”

The coat of arms of the Olmo family, featuring a spouting fountain and a stalk of wheat on either side of a verdant tree, is prominently depicted on the frontispiece within a gilt medallion. Israel Barukh Olmo, the recipient of this diploma, was born in Ferrara to Jacob Daniel Olmo (1690-1757), a noted Italian rabbi and poet. Jacob served as the head of the yeshivah in Ferrara and also as the rabbi of the Ashkenazi synagogue. He authored numerous works including occasional poems and hymns, legal decisions, a poetic drama entitled Eden Arukh, as well as a volume documenting the rabbis of the Ashkenazi synagogue of Ferrara. Israel Barukh Olmo followed in his father’s footsteps and, in addition to his medical studies, authored occasional poems such as the one celebrating the wedding of Asher Chefetz (Anselmo Gentili) and Abigail Luzzatto circa 1750 (JTS library MS 9027 V1:9).

Literature & References: Vivian B. Mann, ed. Gardens and Ghettos: The Art of Jewish Life in Italy (1989), p. 235; Natalia Berger, Jews and Medicine: Religion, Culture, Science (1995).

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Lot 169: A Magnificent Illustrated Esther Scroll, from Prague, ca. 1700

Estimate: 100,000—120,000 USD. Hammer Price with Buyer’s Premium: 134,500 USD

Ink on parchment (12 ¼ x 103 in.; 310 x 2620 mm). Text written in square Hebrew script arranged in 16 columns of 25 lines on four membranes. Few very light stains. Housed in a turned cylindrical wooden case.

Ink on parchment (12 ¼ x 103 in.; 310 x 2620 mm). Text written in square Hebrew script arranged in 16 columns of 25 lines on four membranes. Few very light stains. Housed in a turned cylindrical wooden case.

This splendid scroll of Esther is an extremely rare example of a megillah with a superb engraved border created by the artist Paul-Jean Franck. The eighteenth century witnessed the growth and success of numerous publishers of Hebrew books. These printers, presumably looking to further expand their market, undertook to produce illustrated megillot for use on the holiday of Purim. Recognizing that according to Jewish law, Esther scrolls must be written by hand in order to be ritually fit, the printers engraved highly decorative borders onto prepared parchment and left blocks of blank space within these borders, so that a scribe might insert the biblical text. The majority of eighteenth-century megillot with engraved borders were produced in Amsterdam and Venice. This Bohemian scroll, however, is an exceptionally rare example of a printed border published outside of these two centers. The signature of its remarkably skilled engraver, Paul-Jean Franck, can be found in the first panel of this scroll. . .

Literature & References: Cohen, Mintz and Schrijver. A Journey through Jewish Worlds. Highlights from the Braginsky Collection of Hebrew Manuscripts and Printed Books (Amsterdam: 2009), pp. 266-67.

For the full description, click here»

Happy Thanksgiving!

Two eighteenth-century offerings to celebrate the U.S. holiday:

Philipp Ferdinand de Hamilton (?), "Wild Turkey," ca. 1725-1750 (Chicago: Smart Museum of Art)

1) By clicking here, you can listen to a fascinating lecture (recorded 23 March 2006) from the food historian Elizabeth Reily on the topic of “Benjamin Franklin and the Wild Turkey.” The lecture is made available by the Forum Network, a public media service of PBS and NPR.

2) The painting shown at the right is part of the collection of the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago. The following description by Ingrid Rowland comes from the exhibition catalogue, which she edited, The Place of the Antique in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, 1999), pp. 95-96:

By the early eighteenth century, painted reveries like this lively portrayal of a wild turkey combined the precision of Dutch still life with the epic sweep of Italian baroque histories . . . This wild turkey, a New World bird, perches among other birds large and small above a battered fragment of carved stone relief, while in the background an Egyptian sphinx crouches on its high pedestal . . . . A likely candidate for that owner is Prince Eugene of Savoy, whose Belvedere Palace in Vienna boasted a sphinx among its many antiquities and an aviary as part of its menagerie. The prince’s birds, beasts, gardens, and antiquities were all commemorated in a series of twelve engravings by Salomon Kleiner (1734) . . . Prince Eugene also commissioned such stagey views of nature and antiquity from painters like Philip Ferdinand de Hamilton, a Belgian of Scots family who emigrated to Vienna before 1700, and the Viennese Ignaz Heinitz von Heintzenthal. . . . of the two, de Hamilton worked in an intimate style closer to that of the Smart painting. . . .

Chinoiserie in the Bedroom

Today at Style Court, Courtney Barnes addresses four-poster beds, including John Linnell’s exquisite Badminton Bed, ca. 1754, from the collection of the Victoria and Albert. A design blog with a focus on interiors, Style Court regularly covers a variety of artistic topics with an interest in bridging the worlds of the academy and the museum for a wider, general public.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From the V&A’s website:

The exotic form of this bed was inspired by Chinese pagodas. The design and the pierced fretwork back are similar to garden tea pavilions built in the Chinese style and found in large gardens throughout Britain and Europe from about 1730. Chinese decoration was particularly popular for ladies’ bedrooms and dressing rooms.

Although the payments for the bed and other bedroom furniture were made jointly by the 4th Duke and Duchess of Beaufort, evidence in the Duchess’s private notebooks shows that she was particularly interested in this commission and probably discussed the details with the designer and craftsman John Linnell and his father William Linnell.

The bed hangings had been replaced with scarlet woollen hangings by 1835, although the bedding still included the original 18th-century hair mattress which was acquired with the bed by the Museum in 1921. In addition there was a feather bed, three blankets, a wool mattress, a straw paliasse (another form of mattress) and a Marsella quilt. In 1929 a replica of the bed was made for the Chinese Bedroom at Badminton House by Angell of Bath.

Westwood on the Wallace: ‘A Jewel Box for Jewels’

Hearing British fashion designer Vivienne Westwood side with “culture” over “consumerism” and observe that the central figure in Fragonard’s The Swing is “not wearing any knickers” may not offer the most insightful glimpses into the eighteenth-century, but this YouTube clip perhaps still provides an interesting example of the connections between contemporary fashion and the French Rococo. That it appears on the Wallace’s own website also speaks to the museum’s marketing strategies (for all of the similarities between the Wallace and the Frick, it’s more difficult to imagine the venerable New York institution adopting such an approach). Depending upon your state of mind, the video can be just wonderfully entertaining.

leave a comment