Paragone in Eighteenth-Century England

From the Henry Moore Institute’s website:

Subject/Sitter/Maker: Portraits from an Eighteenth-Century Artistic Circle

Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, 15 August — 14 November 2010

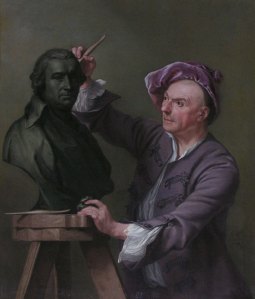

This small exhibition sets up close comparisons between the painted and the sculpted portraits of the actor David Garrick and the sculptor Louis François Roubiliac, asking us how we measure likeness, and how we understand the concept of the professional homage, as one artist depicts another.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

In The Observer (23 August 2009), Rachel Cooke writes that the exhibition

is truly a pint-sized show in the sense that it can be seen in less time than it would take you to drink one: it consists, in fact, of just two paintings, two sculptures and one monochrome print. . . [It] prods at the respective merits of sculpture and painting, and their sometimes vexed relationship, by looking at likenesses of the actor, manager and patron of the arts David Garrick and the sculptor who made him his subject more than once, Louis-François Roubiliac. . . A bust of Garrick attributed to Roubiliac is the third piece in Subject/Sitter/Maker . . . Garrick’s face is noble looking, but it also has a varnished quality, one you cannot blame on its media (plaster and paint) alone. He looks so blank, and so still: like a drink, waiting to be poured. But then you remind yourself that he was an actor – the great impersonator – and you begin to wonder whether this lacquered effect was not very deliberate. Next to this bust is a portrait by Andrea Soldi of Roubiliac at work on it. Look at this, and at JW Cook’s print, after Adrien Carpentiers, of Roubiliac modelling a small statue of Shakespeare, and you become doubly convinced. For sure, these are stagey works, Roubiliac’s cuffs artfully unbuttoned and peeled back so as not to impede his progress; and we know that the Shakespeare terracotta on which he is depicted to be working was completed four years earlier. But there is such beadiness in his eyes, such energy in his forearms, and he looks so hungry – though perhaps it was the case that he was actually famished, as well as creatively so: while Garrick grew ever more rich and famous, buying himself a Robert Adam house with grounds by Capability Brown, poor old Roubiliac died penniless. Even in the 18th century, ticket sales were obviously more reliable than the cheques of wealthy men.

leave a comment