Exhibition | The U.S. Constitution and the End of American Slavery

Press release (24 November 2014) from The Huntington:

The U.S. Constitution and the End of American Slavery

The Huntington, San Marino, California, 24 January — 20 April 2015

Curated by Olga Tsapina

In commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the passage of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens will illuminate the complexities of ending slavery with an exhibition drawn from its renowned collections of American historical manuscripts and prints. “The U.S. Constitution and the End of American Slavery” will be on view in the West Hall of the Library from January 24 until April 20, 2015.

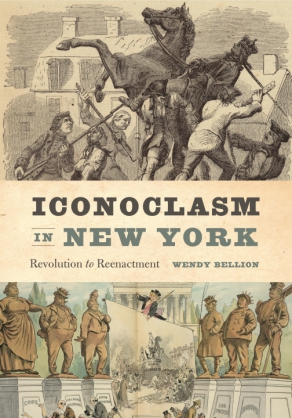

Thomas Jefferson, notes on the 12th Amendment, ca. 1803 (The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens)

“The exhibition follows a long, tortuous, and bloody road that led to that fateful vote,” said Olga Tsapina, the Norris Foundation Curator of American Historical Manuscripts and curator of the exhibition. On January 31, 1865, Schuyler Colfax, the speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, called for a vote on a joint resolution that would amend the Constitution to abolish slavery throughout the United States and empower Congress to “enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” After the clerk read the tally—119 ayes to 56 nays, with eight abstaining—the House erupted in wild jubilation. American slavery was dead. “The 119 congressmen who voted ‘aye’ on January 31, 1865, accomplished two things that seemed nearly impossible—abolishing slavery and amending the U.S. Constitution,” Tsapina added.

Many hurdles stood in the way of ending slavery: racism, fear, political partisanship, economic interests, and the lack of political will, to name a few. The Constitution presented the most formidable obstacle. The very same national charter that had created a republic dedicated to liberty also guaranteed the rights of Americans who owned human property, said Tsapina. For example, the Constitution mandated that each state respect the other states’ laws, even while Southern states permitted ownership of slaves. “But this is just one area of the Constitution that was problematic,” she added. “There were many others, and they all factored into what was a tremendously complicated—and daunting—matter.”

The conflict between the foundational principles of liberty and the reality of American slavery proved to be irreconcilable. After decades of increasingly bitter discord, it finally broke the Union apart, plunging the nation into civil war in 1861. Even the war failed to end human bondage. That was achieved only by changing the Constitution in a way its framers could not have imagined.

Featuring some 100 manuscripts, rare books, prints, and photographs, most exhibited for the first time, the exhibition will offer Huntington visitors a rare opportunity to experience the history of what Colfax called “that great measure, which hereafter will illuminate the highest place in our History” through the extraordinary breadth and depth of The Huntington’s collections.

The exhibition includes the writings of abolitionists and slave masters; runaway slaves and slave speculators; African American emigrants to Liberia and members of the Underground Railroad; and legal scholars and leaders of political parties. Visitors will see manumissions (formal documents freeing slaves from servitude) and slave traders’ business correspondence, letters from Civil War battlefields, and congressional speeches and resolutions, as well as political cartoons representing viewpoints from both sides of the partisan divide.

The display includes a 1796 letter by President George Washington discussing the fate of his runaway slave, Ona Marie ‘Oney’ Judge; Thomas Jefferson’s notes on amending the Constitution; a notebook from the famous abolitionist John Brown; and the writings of Francis Lieber, the celebrated author of the U.S. Army military code that was praised as “better than the Emancipation Proclamation.” The exhibition will feature letters and manuscripts from The Huntington’s famous collection of Abraham Lincoln material, including Lincoln’s record of his debates with Stephen A. Douglas and a copy of the 13th Amendment signed by the president.

“‘The U.S. Constitution and the End of American Slavery’ tells a complex and fascinating story in which the fate of American slavery was decided not only on Civil War battlefields, but also in courtrooms, the debating floors of state legislatures and the chambers of the U.S. Congress, as well as in proverbial smoke-filled rooms,” said Tsapina.

Display | Working Women: Images of Female Labor

From The Huntington:

Working Women: Images of Female Labor in the Art of Thomas Rowlandson

The Huntington, San Marino, California, 20 December 2014 — 13 April 2015

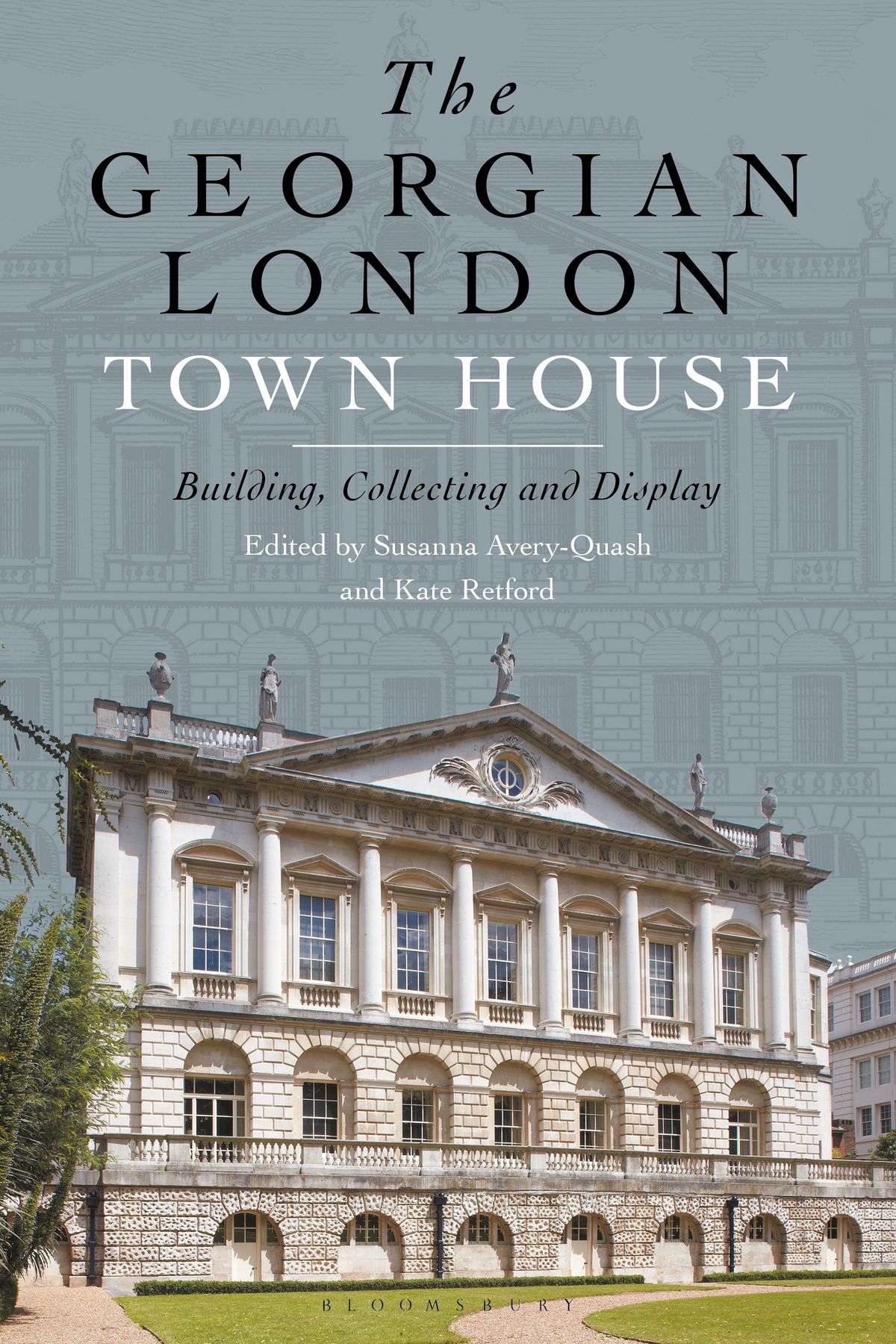

Thomas Rowlandson, A French Frigate Towing an English Man o’ War into Port, no date, pen and watercolor (The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens; Gilbert Davis Collection)

As one of Britain’s premier draftsmen, Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) lent his vast talent to the comic depiction of a wide range of topics, from politics to pornography. His satirical views of Georgian society are among his strongest work, and The Huntington’s collection focuses primarily on this aspect of his oeuvre. Rowlandson’s observations of the follies of the world around him provide us with a view of late 18th- and early 19th-century England that goes beyond what we see in aristocratic portraits or in the prose of Jane Austen, which portray a world of grand ladies and gentlemen and genteel manners.

This display of 11 rarely-exhibited watercolors from the collection focuses on Rowlandson’s depiction of women. His subjects are primarily those who were most visible within the public sphere—street vendors, servants, actresses, and prostitutes as they plied their various trades—with an occasional glance at the foibles of the upper class. Eschewing complex political or philosophical messages, Rowlandson’s images, though humorous, provide a fascinating glimpse into the reality of women’s lives at this time.

leave a comment