At Auction | Portrait Bust by Houdon at Sotheby’s

Press release from Sotheby’s:

Sotheby’s: Important Old Master Paintings and Sculpture, N08952

New York, 31 January and 1 February 2013

Sotheby’s Sale N08952, Lot 397. Jean-Antoine Houdon, Portrait of Jacques-Antoine-Hippolyte, the Comte de Guibert, 1791

Estimate: 800,000 – 1,200,000 USD

Important sculpture and works of art will be up for offer on 1 February 2013 during the second day of Sotheby’s Old Master Paintings and Sculpture sale in New York and will be highlighted by a commanding French marble bust of one of France’s foremost military tacticians Jacques-Antoine-Hippolyte, the Comte de Guibert. The bust was commissioned on 2 November 1791 from Houdon, the preeminent portrait sculptor of his time, by the sitter’s widow (est. $800/1.2 million). Guibert was a general, a writer and a friend to many of the Enlightenment’s leading intellectuals, and his Essai général de tactique had an enormous impact on the science of military strategy and was admired by George Washington, Frederick the Great, and the young Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1776, the year he was promoted to colonel, he was raised to the nobility as a count of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1781 he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general, and in 1778 he was promoted to the rank of marechal de camp. The work, which exemplifies Houdon’s mastery of the material and his fondness for both naturalistic detail and psychological realism, conveys the sitter’s strength, intelligence and virility. This marble bust remained in the Guibert family through 1918.

A further highlight is a beautifully carved pietra serena frieze by Francesco di Simone Ferrucci (1437-1493), a talented disciple of Verrocchio, which most likely adorned the lintel of a fireplace in the palazzo of a noble Florentine family circa 1460-1470 (est. $500/700,000). The present relief is centered by the coat of arms of the Tuscan counts, Guidi di Bagno, who were one of the largest and most powerful noble families in central Italy in the Middle Ages. The majority of pieces by Ferrucci are preserved in museum collections or in their original church installations, including a similar pietra serena frieze in the Museo Bardini, Florence and another in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. The outstanding clarity of form and detail in this frieze is underscored by the material from which it was carved. Pietra serena is a hard and fine-grained stone from Fiesole which was employed by Tuscan sculptors throughout the Renaissance. Here, Ferrucci was able to achieve a sense of depth, with very shallow relief, using of a variety of finely chiseled textures and contours. This impressive pietra serena frieze comes from the Collection of an Italian noble family.

A poignant South German limewood figure of the grieving Saint John from the workshop of Tilman Riemenschneider circa 1490 is estimated at $250/350,000. Riemenschneider was arguably the preeminent medieval German sculptor and this figure was probably carved for an altar. Few sculptures by Riemenschneider and his workshop remain in private hands.

Also included in the sale are nine rare terracotta anatomical sculptor’s models (est. $200/300,000) formerly in Paul von Praun’s famed collection in Nuremberg and attributed to accomplished sculptor Johann Gregor van der Schardt. Dating to the late 16th or early 17th century, the models have been consigned by and will benefit the Museum of Vancouver. Six of the nine models on offer are recognizable as studies after anatomical elements seen in famous monuments sculpted by Michelangelo. These terracottas are rare examples of study-models of Michelangelo’s work by this talented younger artist working within the master’s lifetime or shortly after his death. For decades, the unsigned terracottas were attributed to Michelangelo; however, extensive research and stylistic comparisons led scholars to determine that these Renaissance models were executed by Northern sculptor Johann Gregor van der Schardt who worked extensively in terracotta and was a follower of Michelangelo. Von Praun acquired the contents of van der Schardt’s studio after the artist’s death circa 1580, and these models were most likely among the contents purchased. Only one signed work by van der Schardt survives: a bronze statuette of Mercury probably presented to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximillian II in Vienna circa 1569. The collection of Paul von Praun, a wealthy Nuremberg silk merchant, was one of the most extensive of its time, comprised of works by Leonardo, Raphael and Titian, and it was one of the first to include a comprehensive, international group of contemporary sculpture. He also owned a pair of terracottas of Dawn and Night, after Michelangelo’s marbles for the Medici Chapel at San Lorenzo in Florence, which are now on exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. After von Praun’s death in 1616 the collection was kept together by his heirs and displayed in Nuremberg, later known as Praunsche Kabinett. Among its visitors were Goethe and Marie Antoinette before its sale in 1801.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Viewing Schedule in New York

Friday, 25 Jan | 10:00-5:00

Saturday, 26 Jan | 10:00-5:00

Sunday, 27 Jan | 1:00-5:00

Monday, 28 Jan | 10:00-5:00

Tuesday, 29 Jan | 10:00-5:00

Wednesday, 30 Jan | 10:00-5:00

Thursday, 31 Jan | 10:00-5:00, sculpture only

Friday, 1 Feb | 10:00-12:00, sculpture only

At Auction | Portrait of a Boxer at Bonhams

Press release (8 January 2013) from Bonhams:

Bonhams — Gentleman’s Library Sale (20448)

London, 29 January 2013

Bonhams Sale 20448, Lot 185, Portrait of the Pugilist

George ‘The Coachman’ Stevenson, 1742

Estimate 16,000 – 24,000 USD

An extremely rare early portrait of a boxer, George ‘The Coachman’ Stevenson 1742, whose tragic death led to the first set of rules for boxing, is being sold by Bonhams on January 29th in the Gentleman’s Library Sale in Knightsbridge. The English School Portrait of the Pugilist George ‘The Coachman’ Stevenson, 1742, an oil on canvas, is estimated to sell for £10,000-15,000.

Stevenson died a few days after a bout against the English champion, Jack Broughton, an event that led Broughton to draw up a code of rules in order to prevent a recurrence. Published as ‘Broughton’s Rules’ they were the first boxing rules and were universally used until 1838.

Alistair Laird a specialist in Bonhams Nineteenth-Century Paintings Department says: “I have never seen an eighteenth-century picture to do with boxing in my 30 years in art auctions. This is an extremely rare image.”

The Yorkshireman George Stevenson, had fought the English champion Jack Broughton on the 17th of February 1741 in a fairground booth on Tottenham Court Road. Unfortunately, Stevenson died a few days after his 45-minute fight, an event that triggered Broughton to draw up a code of rules in order

to prevent a recurrence.

Published on 16 August 1743, ‘Broughton’s Rules’ applied to the bare-knuckle Prize Ring and included ‘That no person is to hit his adversary when he is down, or seize him by the ham, the breeches, or any part below the waist; a man on his knees to be reckoned down’. Otherwise much was left to the discretion of referees. Rounds were not of a fixed length but continued until one of the fighters was knocked or thrown to the ground, after which those in his corner were allowed 30 seconds to return him to the ‘scratch’ – the middle of the ring – failing which his opponent was declared the victor.

Broughton’s rules were universally used until 1838. He was buried in Westminster Abbey in recognition of his contribution to English boxing. The sport enjoyed an unprecedented surge in popularity during the Regency period when it was openly patronized by the Prince Regent, (later George IV) and his brothers. Championship boxing matches acquired a louche reputation as the places to be seen by the wealthy upper classes. Thus a match would often be attended by thousands of people, many of whom had wagered money on the outcome.

New Book | Daniela Bleichmar’s ‘Visible Empire’

From The University of Chicago Press:

Daniela Bleichmar, Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 288 pages, ISBN: 978-0226058535, $55.

Between 1777 and 1816, botanical expeditions crisscrossed the vast Spanish empire in an ambitious project to survey the flora of much of the Americas, the Caribbean, and the Philippines. While these voyages produced written texts and compiled collections of specimens, they dedicated an overwhelming proportion of their resources and energy to the creation of visual materials. European and American naturalists and artists collaborated to manufacture a staggering total of more than 12,000 botanical illustrations. Yet these images have remained largely overlooked—until now.

Between 1777 and 1816, botanical expeditions crisscrossed the vast Spanish empire in an ambitious project to survey the flora of much of the Americas, the Caribbean, and the Philippines. While these voyages produced written texts and compiled collections of specimens, they dedicated an overwhelming proportion of their resources and energy to the creation of visual materials. European and American naturalists and artists collaborated to manufacture a staggering total of more than 12,000 botanical illustrations. Yet these images have remained largely overlooked—until now.

In this lavishly illustrated volume, Daniela Bleichmar gives this archive its due, finding in these botanical images a window into the worlds of Enlightenment science, visual culture, and empire. Through innovative interdisciplinary scholarship that bridges the histories of science, visual culture, and the Hispanic world, Bleichmar uses these images to trace two related histories: the little-known history of scientific expeditions in the Hispanic Enlightenment and the history of visual evidence in both science and administration in the early modern Spanish empire. As Bleichmar shows, in the Spanish empire visual epistemology operated not only in scientific contexts but also as part of an imperial apparatus that had a long-established tradition of deploying visual evidence for administrative purposes.

Daniela Bleichmar holds a joint appointment in the Departments of Art History and History. She received her BA from Harvard University and her Ph.D. in History (History of Science) from Princeton University, where she trained as a cultural historian of early modern science, specializing in the history of visual culture and the natural sciences in Europe and the Spanish Americas in the period 1500-1800. Her research and teaching address the history of the Spanish empire, early modern Europe, visual and material culture in science, collecting and display, and the book, print, and prints.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

C O N T E N T S

Introduction: Natural History and Visual Culture in the Spanish Empire

1: A Botanical Reconquista

2: Natural History and Visual Epistemology

3: Painting as Exploration

4: Economic Botany and the Limits of the Visual

5: Visions of Imperial Nature: Global White Space, Local Color

Conclusion: The Empire as an Image Machine

Acknowledgments

Notes

Bibliography

Index

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

“The history of late eighteenth-century Latin America is often told simply as the Creoles’ ever-increasing disenchantment with an unenlightened Mother Spain. Daniela Bleichmar’s remarkable book offers us a different history, one in which an Enlightenment study of natural history takes center stage. She casts before the reader passionate and dedicated men of learning and the arts who under Spanish royal sponsorship were entrusted to perform precise observation of the natural fruits of divine creation and render them into splendid and copious scientific illustrations; the results of ‘artful looking . . . a barometer of Enlightenment thought.’ Bleichmar provides more than just an account of these accomplishments; she wields an interdisciplinary brilliance that melds the best of the history of science, art history, and history and serves up a critical and fascinating examination of Linnean classification, scientific illustration, and their complex intersection, scientific and social, in recording the flora of South America.”—Thomas B. F. Cummins, Harvard University

The Wallace Treasure of the Month for January 2013

January 2013’s Treasure of the Month from The Wallace:

Two Overdoors from Marie-Antoinette’s Bedroom in the Château of Marly

Gallery talks with Christoph Vogtherr, Wallace Collection, London, 11 and 24 January 2013, 1pm

The château of Marly was situated north of Versailles not far from the river Seine. It had been built for Louis XIV between 1679 and 1684. Together with its spectacular park it served as an exclusive retreat for the French King who bestowed invitations as a particular favour to selected courtiers and the Royal family. Marly consisted of a central building for the King and his immediate family (the Royal Pavilion) and twelve pavilions for guests. For a century, the château was repeatedly modernised until it was sold by the Revolutionary government and demolished in 1806.

The château of Marly was situated north of Versailles not far from the river Seine. It had been built for Louis XIV between 1679 and 1684. Together with its spectacular park it served as an exclusive retreat for the French King who bestowed invitations as a particular favour to selected courtiers and the Royal family. Marly consisted of a central building for the King and his immediate family (the Royal Pavilion) and twelve pavilions for guests. For a century, the château was repeatedly modernised until it was sold by the Revolutionary government and demolished in 1806.

The two paintings in the Wallace Collection were part of the remodelling of the Queen’s bedroom for Marie-Antoinette in 1781. At that time a mezzanine was added to the room and as a consequence its overall height reduced. The new decoration of the room took these changes into account and new overdoor paintings were required to react to the changed dimensions of the room.

The commission was given by the Direction des Bâtiment (the building administration) to Nicolas-René Jollain (1732-1804) and Hughes Taraval (1729-1785), two members of the Royal Academy. They have since been almost forgotten, and both their works had been acquired by the 4th Marquess of Hertford as by the much better known Fragonard, an indication that the signatures must have been covered. It is, however, possible to link the two works with the overdoors for the Queen’s bedchamber documented in the sources. Their decorative character is in line with Marie-Antoinette’s preferences whose taste in the Decorative Arts was cutting edge while most of the paintings commissioned for her, except portraits by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, are much more conventional. Equally traditional is the iconography of the two works: Putti are depicted as allegories of Sleep (by Jollain) and Awakening (by Taraval), obvious choices for a bedroom.

The overdoors are beautifully decorative works. The figures are arranged in a triangular composition in both works to visually link the pair. Their pastel-like palette responded to the light colour scheme of the room, the slightly elongated figures to their position high up above the doorways. On closer inspection the works show a smoother and more detailed brushwork typical for the late eighteenth century.

The Queen’s apartment was situated in the North-West corner of the building. The two overdoors were inserted into the South and East walls. The different angles of lighting on the paintings respond to their situation relative to the windows. Taravals painting must have been on the South wall where the light falls in from the right, Jollains on the East side of the room, right next to the Queen’s bed where an allegory of sleep is particularly appropriate.

After the French Revolution, the paintings were sold by the revolutionary government together with the entire contents of Marly. A drop-front desk and a corner cabinet by Jean-Henri Riesener in the Wallace Collection (also in the Study) same room once were part of Marie-Antoinette’s furniture in Marly.

Gallery Talks with Christopher Vogtherr: Friday 11 and Thursday 24 January at 1pm.

Further Reading

John Ingamells, The Wallace Collection Catalogue of Pictures III. French before 1815 (London 1989).

Stéphane Castelluccio, Le château de Marly sous le règne de Louis XVI (Paris 1996).

Exhibition | Peru: Kingdoms of the Sun and Moon

Press release (26 October 2012) from the MMFA:

Peru: Kingdoms of the Sun and Moon: Identities and Conquest

in the Early, Colonial and Modern Periods

Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2 February — 16 June 2013

Seattle Art Museum, 17 October 2013 — 5 January 2014

Curated by Victor Pimentel

Mochica, North Coast, possibly La Mina, Forehead ornament with feline head and octopus tentacles ending in catfish heads (100 – 800 A.D.), Gold, chrysocolla, and shells. 28.5 x 41.4 x 4.5 cm (Museo de la Nación, Lima. Photo: Daniel Giannoni)

Organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Peru: Kingdoms of the Sun and Moon will display an extensive collection of pre-Columbian treasures and masterpieces from the colonial era to Indigenism, including over 100 pieces that have never before been seen outside of Peru. With more than 350 works of art (paintings, sculptures, gold and silver ornaments, pottery, photograph, works on paper, and textiles) on loan from public and private collections in Peru, Canada, United States, France, and Germany, this exhibition covers roughly 3,000 years of history, including archaeological discoveries in recent decades.

“In conceiving this exhibition on the question of identity in Latin America following our exhibition Cuba! Art and History from 1868 to today presented in 2008, I was fascinated to discover the extent to which archaeology has revealed this birthplace of civilization – one of six such in the world – only recently in the course of the 20th century” explains Nathalie Bondil, Director and Chief Curator of the MMFA. “This exhibition demonstrates how the retrospective view of history shifted from a colonial interpretation to a new nationalist feeling in the course of the modern era. This complex project brings together numerous loans, both public and private, from Peru, some of which have not been exhibited before. Above all, the display features paintings of the era subsequent to the Spanish Conquest and, for the first time outside Peru, of the Indigenist period after independence. The constant elements of a civilization built up over millennia open up perspectives never before opened,” she added.

Anonymous, Cuzco School, Virgen Niña Hilando (Young Virgin Spinning), second third of the 18th century, oil on canvas, gold leaf. 112.5 x 80.5 cm

(Lima: Museo Pedro de Osma. Photo: Joaquín Rubio)

Mythical Peru, cradle of Andean civilization, and its pre-Hispanic, colonial and modern history will be examined in the four sections of the exhibition as follows:

• Section 1 (introduction) will explain how archaeology rewrote the national history beginning with the discovery, in 1911, of Machu Picchu to the recent restitution of artworks.

• Section 2 will focus on the myths and rituals of the early civilizations of the Andes, highlighting their role in forming and shaping Peruvian identity during the pre-Columbian era.

• Section 3 will illustrate the perpetuation, concealment, and hybridization of the indigenous culture during the colonial period.

• The last section will highlight the rediscovery of this culture in the 20th century and the revalorization of ancient symbols of identity in contemporary Peruvian iconography.

Adds Exhibition Curator Victor Pimentel, Curator of Pre-Columbian Art at the MMFA, “Through the representation and reinterpretation of myths, rituals and other primordial symbols of identity captured by different artistic traditions, the exhibition will illustrate how the evocative power of images have influenced the history of pre-Hispanic, colonial and modern Peru.”

Illustrating the beliefs and rituals of pre-Columbian societies

The relationship with death, particularly the constant dialogue between the world of the living and the world of the dead, is an essential component of Andean spirituality. Among the Mochicas, ceremonial sacrifices contributed to the perpetuation of the supernatural and social orders, while ancestor worship held significant importance to the Lambayeque and Chimú cultures.

In order to illustrate the beliefs and rituals that dominated the life of pre-Columbian societies, the exhibition will focus on objects associated with the sacrificial ceremony of the Mochica people (200 B.C. to 800 A.D.) and the funerary rites of the Chimú and Lambayeque cultures (11th to 15th century A.D.), by presenting some of the most complete depictions of these rituals. On display will be important objects in gold, silver, and turquoise from the royal tombs of Sipán, discovered in 1987 by archaeologist Walter Alva, constituting the most significant find made in Peru since that of Machu Picchu. They include:

• A gold ear disc depicting the Lord of the place, the Mochica governor

• A Mochica ornament in the shape of a half-feline, half-octopus recently repatriated and exhibited for the first time

outside of Peru

• Funerary jewelry (crown, ear discs, necklace, pectoral and shoulder-pieces) including a masterpiece of Chimú gold work

• A rare headboard of a Lambayeque litter depicting figures officiating at a ceremony, unique in the complexity of its ornamentation

Religion in Many Forms

The Spanish conquest of Peru in the 16th century led to the hybridization of the Peruvian culture expressed through reinterpretations of mostly religious European art. Paintings of the School of Cuzco – established by the Spanish as a means of converting the Incas to Catholicism – showing Christ, miraculous Virgins, archangels and defenders of the Catholic faith, testify to the powerful role played by images in the campaign to evangelize the Native peoples of the Andes. Included among the examples of paintings mainly by Native artists resulted from this hybridization are:

A Nativity Chest dating from the 18th century, painted with a number of Biblical stories including Adam and Eve, the Annunciation, the Nativity and the visit of the Magi. This three-dimensional illustrated catechism was used to spread Catholicism throughout the Andes.

Among the ceremonial objects on view illustrating the importance of imagery relating to the celebration of the Eucharist in the Andes is a silver Eucharistic urn in the shape of a Pelican, a bird traditionally associated with Christ’s sacrifice. It is widely considered a masterpiece of the liturgical metalwork from the Latin-American Baroque period.

A particularly popular image in art during the Viceroyal period is that of the Virgin. Symbolic representations of the virtuous life of the Virgin Mary on view, such as Young Virgin Spinning, recalls the acllas, the Virgins of the Sun in the Inca empire, whose principal occupation was making garments for the Inca and for religious rites.

Processions also played an important role in the elaboration of a Peruvian identity both as a collective expression of Christian faith and as a means of reinforcing the socio-political positions of the participants. An 18th-century depiction of a splendid Corpus Christi procession, one of the first Christian celebrations to be performed in the colony and still performed to this day, attests to the multi-ethnic nature of the city of Cuzco, the ancient capital of the Inca empire. Coinciding with the celebration of the Inti Raymi, an Inca festival dedicated to the Sun God, Corpus Christi was the most important feast day in the colonial liturgical calendar.

Peruvian art in the 19th and 20th centuries

By 1821, Peruvians had achieved their independence and had formed an indigenous collective memory that combined the idealisation of the pre-Hispanic past, particularly the Inca Empire, with an interest in local subjects. A typical work of Peruvian art of the mid-19th century, Habitante de las cordilleras del Perú (Inhabitant of the Peruvian Highlands) by Francisco Laso, portrays the indigenous peasant as a national symbol for the new Peruvian republic, and heralds the direction that Peruvian cultural nationalism was to take in the next century.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Indigenism flourished as an artistic and intellectual movement based on revalorising and reaffirming Peru’s indigenous heritage. Paintings depicting scenes of Native life and the idyllic landscapes of the Peruvian countryside and highlands such as Pastoras (Shepherdesses) by Leonor Vinatea Cantuarias were to transform the visual culture of Peru in the modern era. This movement is represented in the exhibition by a wide selection of works by José Sabogal, Camilo Blas, Julia Codesido, and Enrique Camino Brent. Widely praised for his documentation of indigenous culture, the only Amerindian included among the major artists associated with the movement is the photographer and portraitist Martín Chambi. Works by Chambi on view include Tristeza andina, La Raya (Andean sadness, La Raya).

An exhibition checklist (PDF) is available here»

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From Abrams:

Victor Pimentel, ed., Peru: Kingdoms of the Sun and the Moon (Milan: 5 Continents Editions, 2013), 384 pages, ISBN: 978-8874396290, $65.

A new publication featuring essays by the foremost experts on the art of Peru The MMFA will produce an accompanying 384-page catalogue co-published in English and in French by the MMFA and 5 Continents Editions in Milan. This fully-illustrated volume (450 illustrations) comprises essays by eminent curators and specialists and interviews with leading figures and experts on Peruvian archaeology, art history, and literature such as the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa.

A new publication featuring essays by the foremost experts on the art of Peru The MMFA will produce an accompanying 384-page catalogue co-published in English and in French by the MMFA and 5 Continents Editions in Milan. This fully-illustrated volume (450 illustrations) comprises essays by eminent curators and specialists and interviews with leading figures and experts on Peruvian archaeology, art history, and literature such as the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa.

Victor Pimentel is curator of pre-Columbian art at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Trying to Think Seriously about Pinterest, Part 2

From the Editor

Open Position: Clerk of the Pinterest Boards

Silivered brass pins, 1620-1800 (London: V&A Museum, given by R. J. Andrews, #123D-1900) Pinned to Cheryl Leigh’s Pinterest Board, 18th-Century Accessories

Last May I invited Enfilade readers to consider how Pinterest might be put to better use for scholars of the eighteenth century. Over the past few months, I’ve grown even more bullish, optimistic about the potential utility of pinning images with texts (organized under headings) and then distributing those pins via a social network (recent stats for Pinterest usage are available here). Pinterest Business accounts were launched in November, and while these may not be precisely the model for establishing scholarly credibility, the offering suggests Pinterest may slowly be growing up. If art historians are well placed to say what’s wrong with most of what happens on Pinterest, it seems to me we might also start contributing models for making a tool like this work better.

For all of these reasons, I’m now accepting applications for a volunteer position I’ve dubbed Clerk of the Pinterest Boards. I’m especially interested in exploring the following problems:

• How and to what extent might Pinterest be used in the production of knowledge, particularly in terms of collecting information (visual and textual information) and presenting that information together?

• How can we make a Pinterest board into something more than merely a collection of ‘pretty’ pictures?

• Are there things Pinterest could do that other digital formats (blogs, Twitter, Facebook, &c.) don’t do or don’t do well?

• How might we increase broad interest in the art and architecture of the eighteenth century via Pinterest?

I’m envisioning this position as extremely flexible and open-ended. As an experiment, it should probably run for at least a year, but the amount of work should be minimal to modest, perhaps an hour or two each week. For the best candidates, you’re probably already spending this much time on exactly the kinds of searches the positions would require; I just need you to start pinning those results and giving some thought to larger questions of organization and goals.

To apply, please send a message of interest and a recent CV to me at CraigAshleyHanson@gmail.com. As always, comments and feedback are welcome.

— Craig Hanson

P.S. — If this talk of pins brings to mind Adam Smith’s example of a “trifling manufacture,” all the better; you’re in the right place.

Exhibition | Italian Tradition of the Quadreria

Now on view at Sperone Westwater:

A Picture Gallery in the Italian Tradition of the Quadreria, 1750-1850

Sperone Westwater, New York, 10 January — 23 February 2013

Francesco Celebrano, Luncheon in the Countryside, 102 x 69 in (260 x 175 cm), ca 1770-80 (New York: Sperone Westwater)

In collaboration with Galleria Carlo Virgilio, Rome, Sperone Westwater is pleased to present A Picture Gallery in the Italian Tradition of the Quadreria, 1750-1850. The exhibition showcases 29 paintings and drawings, all in the Italian figurative tradition, by various European masters created between the mid-18th and mid-19th century.

The exhibition aims to evoke the manner in which collections – known as quadrerie – were formed in Italy in the 18th and 19th centuries, as well as the way in which they were displayed, covering entire walls of the palazzo that housed them. This criterion predates the modern picture gallery, which follows a more scientific idea of classification derived from Illuminism. In addition to satisfying decorative motivations, the arrangement of works within a Quadreria followed the collector’s personal taste, with pictures hung according to related subjects or artistic genres.

Most of the works on view have never been exhibited or published, although many of them are widely documented in literary sources of the time. Firmly grounded in research, the exhibition presents significant works – masterpieces in some cases – by artists who are not widely known beyond specialist academic circles, but who nonetheless have played a key role in art history, with a view to illustrating the progress that research in Italy has made over the past thirty years.

The catalogue accompanying the exhibition groups the works according to artistic or iconographic genre, first with a series of portraits that offer insight into society of the time, followed by history and figure painting – considered the noblest artistic genre in the neoclassical academy tradition – and lastly, landscapes, to illustrate the phenomenon of the Grand Tour with Classical ruins and popular views.

Among the works in the exhibition is a painting by Francesco Celebrano shows members of the aristocracy having a luncheon on a country estate. This painting exemplifies the ancien régime and was likely intended as a model for a tapestry destined for the Neapolitan court. A portrait by Matilde Malechini portrays a French baroness in Rome during the Napoleonic occupation, while Giuseppe Tominz offers an austere, full-length portrait of a member of the new bourgeoisie in Trieste, the founder of the Assicurazioni Generali. The academy nude studies of Francesco Monti and Placido Fabris are followed by two demanding depictions of episodes from Classical history by Gaspare Landi and Pelagio Palagi – influential figures in the artistic circles of Rome and Milan.

The visionary reconstructions of Antiquity in the colored drawings by Giovan Battista Dell’Era counterbalance the series of sentimental mythological evocations by Friedrich Rehberg, Natale Carta and Henry Tresham, who presented his large painting, Sleeping Nymph and Cupid, to the Royal Academy of London in 1797. This section culminates in the romantic Renaissance literary subject by Francesco Podesti. A significant counter-revolutionary allegory by August Nicodemo shows the Dauphin at the tomb of his father, Louis XVI, while another large-format allegory by Francesco Caucig depicts the sentiment/malaise of melancholy with its remedies from Classical medicine.

After the sublime Biblical subject by François Gérard, the monochrome by Bernardino Nocchi of a sculpture by Canova, there follows a series of views of famous buildings of the time such as Hubert Robert’s interior of Palazzo Farnese at Caprarola, and of Classical ruins like the Temple of Diana at Baia in the capriccio by Carlo Bonavia. Two aristocratic travelers admire ruins in the paintings by Andrea Appiani, while an aqueduct is featured in the Roman campagna by Beniamino de Francesco. Volcanoes are the subject of two large-scale paintings by Pierre-Jacques Volaire and Carlo de Paris – the 1771 eruption of the Vesuvius in the Volaire, a virtuoso study of the effects of light caused by the glow of the lava, with lightning and the glare of the moon illuminating the panorama towards Naples and Ischia in the distance. The second volcano is the Pico de Orizaba in Mexico, in a work by a Roman school artist who attempted to document the native customs of Mexico and the grandiose and unspoiled landscapes of that country prior to the imminent transformations that would be brought by civilization. In contrast to this work, there is Antonio Basoli, who produced numerous imaginary views without almost ever leaving his native Bologna.

Curated by Stefano Grandesso, Gian Enzo Sperone and Carlo Virgilio, the exhibition has been produced in collaboration with Galleria Carlo Virgilio in Rome, a gallery that specializes in international art in Italy over the 18th and 19th centuries.

A fully illustrated catalogue will be published on occasion of this exhibition. The book includes an introduction by Joseph J. Rishel, the Gisela and Dennis Alter Senior Curator of European Painting before 1900 and Senior Curator of the John G Johnson Collection and the Rodin Museum, and scholarly entries by Emilie Beck Saiello, J. Patrice Marandel, Fernando Mazzocca, Ksenija Rozman and Nicola Spinosa.

New Book | Modern Antiques: The Material Past in England

From Bucknell UP:

Barrett Kalter, Modern Antiques: The Material Past in England, 1660-1780 (Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2012), 249 pages, ISBN 978-1611483789, $80.

The recovery and reinvention of the past were fundamental to the conception of the modern in England during the long eighteenth century. Scholars then forged connections between linear time and empirical evidence that transformed historical consciousness. Chronologers, textual critics, and antiquaries constructed the notion of a material past, which spread through the cultures of print and consumption to a broader public, offering powerful–and for that reason, contested–ways of perceiving temporality and change, the historicity of objects, and the relation between fact and the imagination. But even as these innovative ideas won acceptance, they also generated rival forms of historical meaning. The regular procession of chronological time accentuated the deviance of anachronism and ephemerality, while the opposition of unique artifacts to ubiquitous commodities exoticized things that straddled this divide.

The recovery and reinvention of the past were fundamental to the conception of the modern in England during the long eighteenth century. Scholars then forged connections between linear time and empirical evidence that transformed historical consciousness. Chronologers, textual critics, and antiquaries constructed the notion of a material past, which spread through the cultures of print and consumption to a broader public, offering powerful–and for that reason, contested–ways of perceiving temporality and change, the historicity of objects, and the relation between fact and the imagination. But even as these innovative ideas won acceptance, they also generated rival forms of historical meaning. The regular procession of chronological time accentuated the deviance of anachronism and ephemerality, while the opposition of unique artifacts to ubiquitous commodities exoticized things that straddled this divide.

Inspired by the authentic products as well as the anomalous by-products of contemporary scholarship, writers, craftsmen, and shoppers appropriated the past to create nostalgic and ironic alternatives to their own moment. Barrett Kalter explores the history of these “modern antiques,” including Dryden’s translation of Virgil, modernizations of The Canterbury Tales, Gray’s Gothic wallpaper, and Walpole’s Strawberry Hill. Though grounded in the ancient and medieval eras, these works uncannily addressed the controversies about monarchy, nationhood, commerce, and specialized knowledge that defined the present for the English eighteenth century. Bringing together literary criticism, historiography, material culture studies, and book history, Kalter argues that the proliferation of modern antiques in this period reveals modernity’s paradoxical emergence out of encounters with the past.

Introduction: The Time Bound and the Modern Antique

Chapter 1 The “Cobweb-Law” and the Fundamental Law: History, Chronology, and Poetic License

Chapter 2 Chaucer Ancient and Modern: Standardization, Modernization, and the Eighteenth-Century Reception of The Canterbury Tales

Chapter 3 DIY Gothic: Thomas Gray and the Medieval Revival

Chapter 4 Horace Walpole’s Fugitive Pieces: Collecting and Ephemerality

Conclusion

Barrett Kalter is Associate Professor of English at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

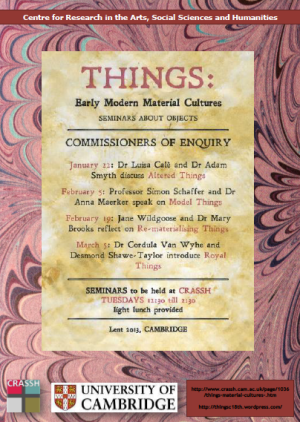

Things: Material Culture at Cambridge, Lent 2013

Programming from CRASSH at the University of Cambridge:

Things: Material Cultures of the Long Eighteen Century

Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities (CRASSH), Cambridge, ongoing series

The seminar meets alternate Tuesdays 12.30-2.30pm in the Seminar Room, Alison Richard Building, West Road. A light lunch will be provided.

The early-modern period was the age of ‘stuff.’ Public production, collection, display and consumption of objects grew in influence, popularity, and scale. The form, function, and use of objects, ranging from scientific and musical instruments to weaponry and furnishings were influenced by distinct and changing features of the period. Early-modern knowledge was not divided into strict disciplines, in fact practice across what we now see as academic boundaries was essential to material creation. This seminar series uses an approach based on objects to encourage us to consider the unity of ideas of this period, to emphasise the lived human experience of technology and art, and the global dimension of material culture. We will build on our success discussing the long eighteenth century in 2012-13 to look at the interdisciplinary thinking through which early modern material culture was conceived, adding an attention to the question of what a ‘thing’ is, to gain new perspectives on the period through its artefacts.

The early-modern period was the age of ‘stuff.’ Public production, collection, display and consumption of objects grew in influence, popularity, and scale. The form, function, and use of objects, ranging from scientific and musical instruments to weaponry and furnishings were influenced by distinct and changing features of the period. Early-modern knowledge was not divided into strict disciplines, in fact practice across what we now see as academic boundaries was essential to material creation. This seminar series uses an approach based on objects to encourage us to consider the unity of ideas of this period, to emphasise the lived human experience of technology and art, and the global dimension of material culture. We will build on our success discussing the long eighteenth century in 2012-13 to look at the interdisciplinary thinking through which early modern material culture was conceived, adding an attention to the question of what a ‘thing’ is, to gain new perspectives on the period through its artefacts.

Each seminar will feature two talks each considering a way of

thinking about objects.

22 January 2013 — Altered Things

Luisa Calè (Birkbeck) and Adam Smyth (Birkbeck)

5 February 2013 — Model Things

Simon Schaffer (Cambridge) and Anna Maerker (Kings College London)

19 February 2013 — Re-materialising Things

Jane Wildgoose (Kingston University and Keeper of The Wildgoose Memorial Library) and Mary Brooks (Durham)

5 March 2013 — Royal Things

Cordula Van Wyhe (York) and Desmond Shawe-Taylor (Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures)

Visit the external blog or subscribe to the group mailing list.

BSECS 2013 Digital Prize | The History of Parliament

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

As noted at The History of Parliament:

As announced at the recent BSECS conference in Oxford, the winner of the BSECS Digital Prize 2013 is The History of Parliament. In the words of the judges:

“The History of Parliament Online is an immensely valuable new resource for scholars of the long eighteenth century. It makes their comprehensive survey of British political history freely available, and presented in a form that is easily navigable and visually attractive.”

The site can be found via the BSECS Links page or directly here»

The prize is funded by Adam Matthew Digital, and GALE Cengage Learning. It is judged and awarded by BSECS. Nominations close on 13 December in any year.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

From The History of Parliament:

This site contains all of the biographical, constituency and introductory survey articles published in The History of Parliament series. Work is still underway on checking and cleaning the data that has been transferred into the website from a number of sources, and the current version of the site is still provisional. In order to find out more about the articles produced by the History, click on the links in the ‘Research’ section above. Additional material – explanatory articles, and images of Members, Parliaments and elections – have been produced specially for the website, and can be found through the ‘Explore’ and ‘Gallery’ sections above. For more information on the History, see the About us section, follow us on Facebook and Twitter or read the HistoryOfParliament, Director and VictorianCommons blogs.

leave a comment